Mixing Secrets – Volume 3: Drums | By Thomas Brett |

Introduction to the series:

In this weekly series of Blogs I’ll attempt to take you through some of the most popular and effective audio processing techniques used in professional studios all over the world.

Each installment of this series will focus on a different instrument and provide you with links to relevant video examples of industry-leading engineers demonstrating these techniques.

This week, we’ll be taking a look at an instrument that forms the foundations on which a solid mix is built:

The sheer amount of variables and decisions that come into play while capturing each individual element makes drums one of the most time-consuming and complex instruments to get right at pretty much every step of the production process.

In this Blog we’ll take a look at some of the many tricks we can use in order to a achieve a punchy, rhythmic backbone of a drum sound.

1 – Make Them Pop! (Transient Enhancement):

An important part to making your drums poke through a dense mix and sound exciting is attack-enhancement.

Here are a few different methods you can use to manipulate your drum transients:

A – Compression For Accentuation:

The most classic way of increasing the initial click/smack of a drum is through the use of slow-attack compression:

Using a compressor with a medium-slow attack between 10-30ms depending on the drum will allow for the initial stick attack to pass through the compression threshold untouched. Alongside helping to level-out the performance, this will also effectively give you “X” amount of additional transient-gain depending on how much compression is being applied to the signal.

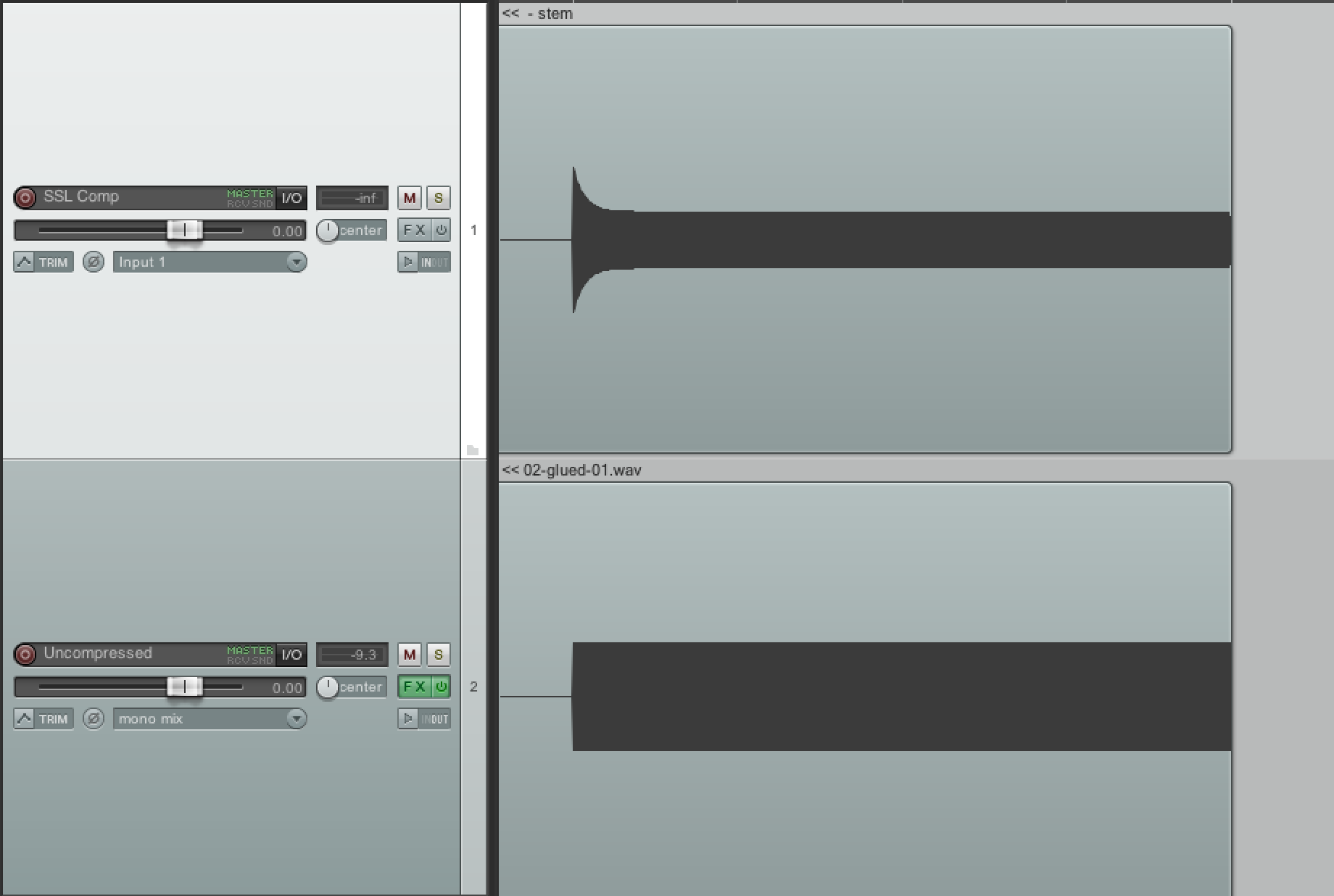

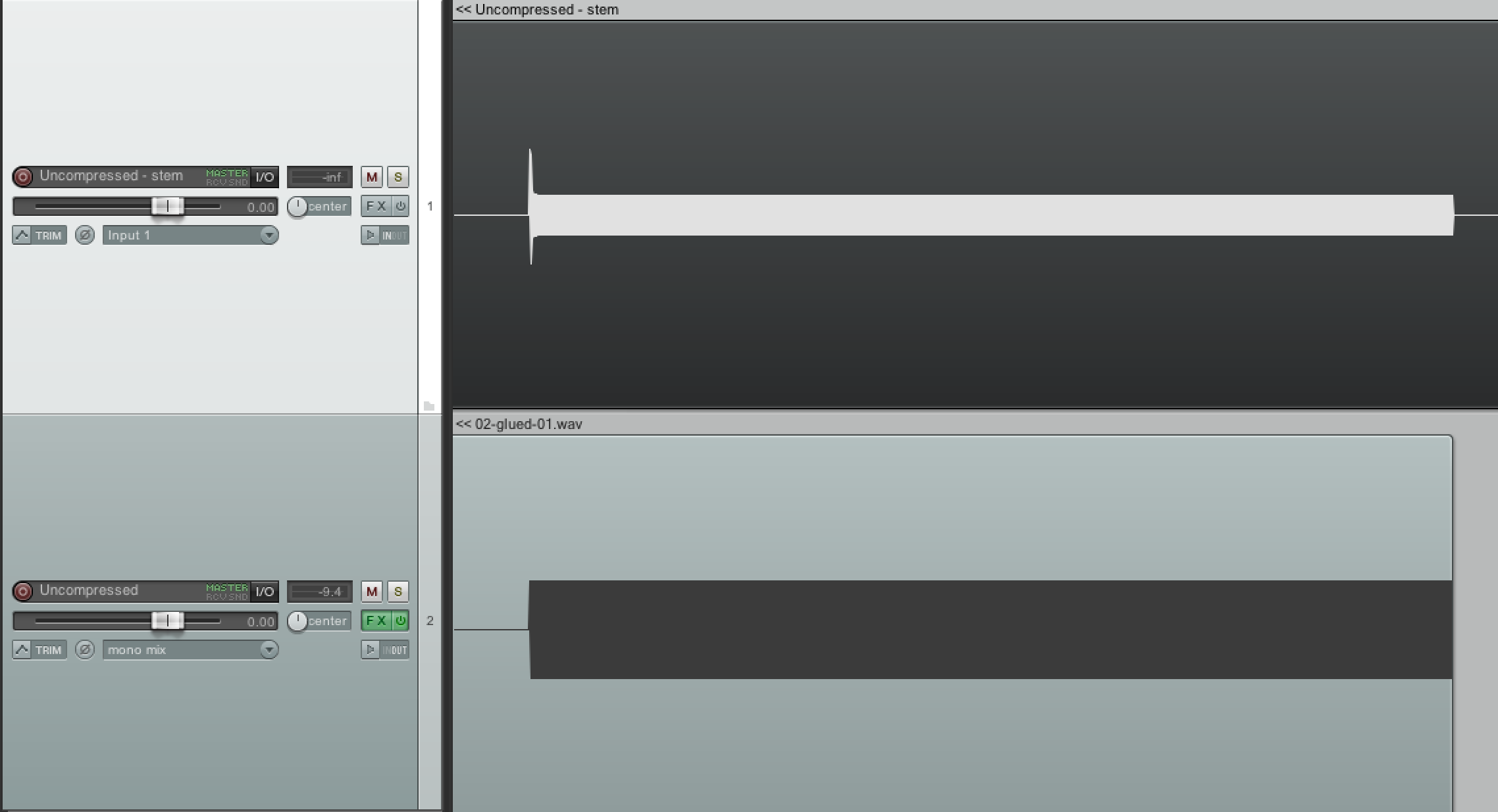

Some Visual Representations Of “Accentuation Compression”:

- Example #1: In the example above I processed a 1kHz sine-wave through an SSL E-Channel Compressor on the “slow” attack setting with -10dB of gain reduction. As you can see from the processed waveform on the first channel, it took around 30ms for the compression to fully kick-in. As a result, we have a nice initial-attack envelope at the beginning of our signal.

- Example #2: In this second example I ran the same test through the SSL compressor’s “fast” attack setting. As you can see, on this setting the compressor is reacting to the signal at a much quicker time of 5ms or so.

Both of the compression settings I’ve demonstrated above are valid, and offer two distinctly different flavours of PUNCH. A good rule of thumb when it comes to compressing drums is to stick between the 10-30ms attack-range in order to just let the initial transients through unharmed.

NOTE: Although you can really go-to-town on trying to perfect your attack times on a per-drum basis, I often find that a simple compressor like the SSL E-Channel does a great job of preventing over-thinking and encouraging a quick workflow.

B – Transient Designers:

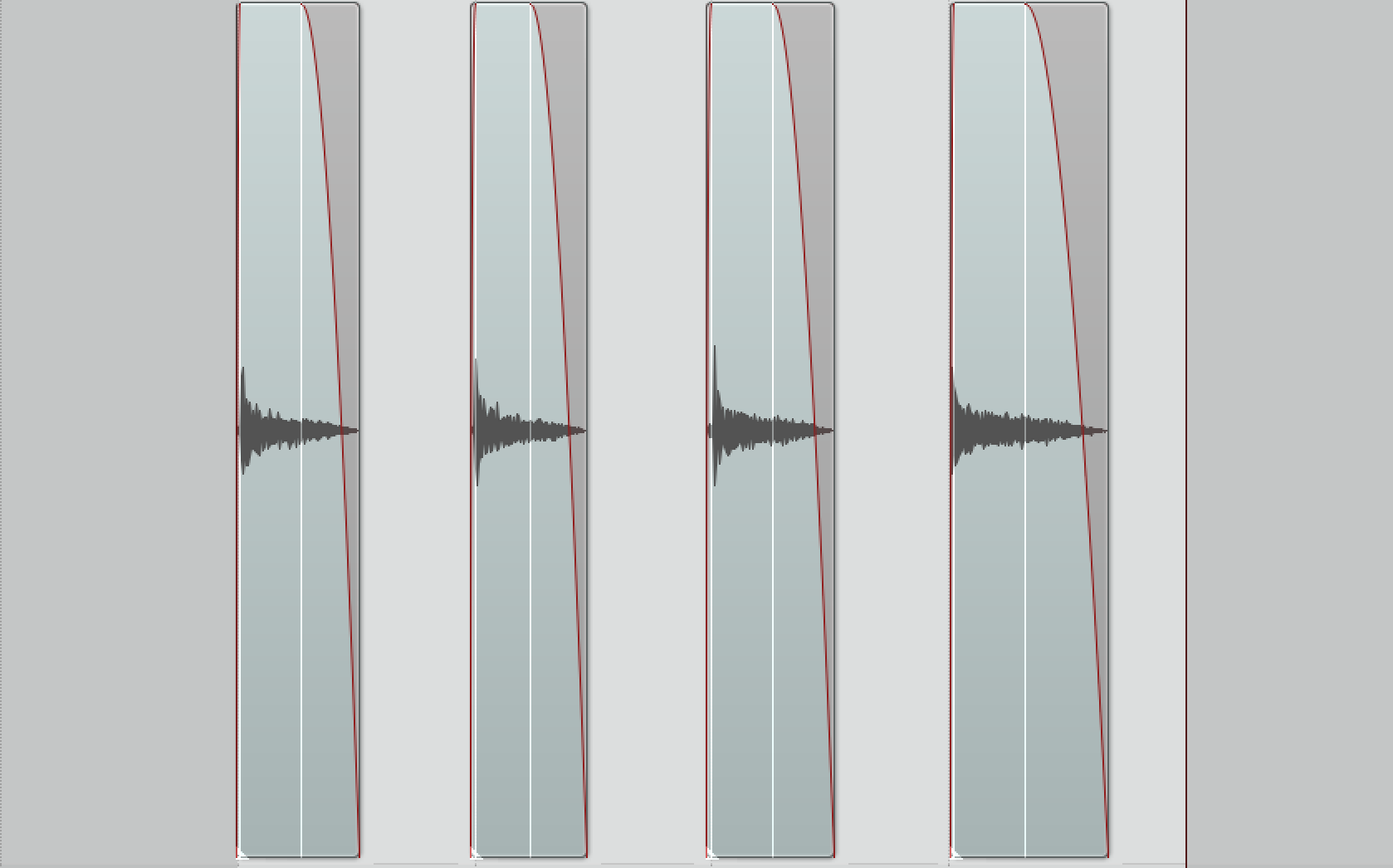

- Full-Spectrum Transient Designers: A transient designer is basically an automatic “smart-volume–envelope-manipulation tool” which gives you the ability to accentuate the attack and sustain portions of a signal with the turn of a few simple knobs. This processing basically achieves a similar transient enhancement effect to the slow-attack Compression method mentioned above, but without any actual compression taking place.

- Multi-Band Transient Designers: Multi-band transient designers offer even greater control over volume envelopes by allowing the user to manipulate the attack and sustain of individual frequency ranges within the signal independently.

Multi-band transient designers such as Joey Sturgis’ “Transify” offer unique processing possibilities such as boosting the high-end stick attack of a snare, or tightening up the low-end sustain of a kick drum. (Just to name a few!)

Multi-band transient designers such as Joey Sturgis’ “Transify” offer unique processing possibilities such as boosting the high-end stick attack of a snare, or tightening up the low-end sustain of a kick drum. (Just to name a few!)

Ryan Bruce “Fluff” Demonstrates JST Transify on A Kick Drum Track:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EyJf3kXzN4w

2 – Bleed Control (Microphone Leakage):

One of the most difficult things to truly master when it comes to playing, recording and mixing the drums is bleed reduction between individual microphones.

Here are a few techniques you can reach for when trying to better-isolate your drum tracks:

NOTE: In this case I’ll only be talking about techniques for the mixing stage, as bleed reduction during recording would require a whole article to itself.

Manual Bleed Removal:

The most accurate way to deal with bleed between drums is to cut it out manually on a per-drum basis:

- Although this is technically the most “perfect” way of eliminating the issue, it is also the most time-consuming.

- How far you should take this process is entirely dependant on how long you’re willing to spend on the tedious, mind-numbing task of frantically moving a mouse around the screen.

- Common practice in most studios is to only remove the bleed from tracks which aren’t played too often (toms, cymbal spot mics etc.) and address bleed on other tracks with a gate or expander.

TIP: The main key to making this type of bleed-removal sound natural in context of the full kit is to play around with your clip fades. Make sure to experiment with various fade-out lengths in order to find a good common ground between “real” sounding drum decays and smooth bleed removal.

Gates/Expanders:

The most common way to remove bleed is through the use of a gate or expander due to the quick and mostly-precise nature of the process:

- These tools are fairly similar to each other: A gate silences the audio (the bleed) entirely once the signal goes below the threshold, while an expander turns the signal down by a user-specified amount rather than cutting it out completely. Both are valid tools, with the expander being a less destructive (and in return more natural) way of dealing with the problem.

My gate/expander of choice is often the dynamics section built in to Waves’ SSL-E channel plugin due to the plugin’s “complete drum toolbox” vibe and overall simplicity.

My gate/expander of choice is often the dynamics section built in to Waves’ SSL-E channel plugin due to the plugin’s “complete drum toolbox” vibe and overall simplicity.

Check out this awesome video of Eric Tarr from “The Pro Audio Files” explaining and demonstrating Gate/Expander usage on Drums:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u48V4jiILbo

Multiband-Expansion:

A fairly modern method of dealing with drum leakage is with multi-band expansion:

- Certain Multi-Band compressors such as Fabfilter’s “Pro-MB” give you the option to switch each band into “expand” mode. This functionality allows the user to partially reduce a specific frequency range of the signal whenever it drops below the chosen threshold.

- In the example above, I’ve set up a single band of expansion across the high-frequencies of a snare track in order to deal with the cymbal bleed between hits.

NOTE: Setting the attack, release and threshold controls so that you’re only letting through each snare hit and the reducing the bleed in between is the key to using this method effectively.

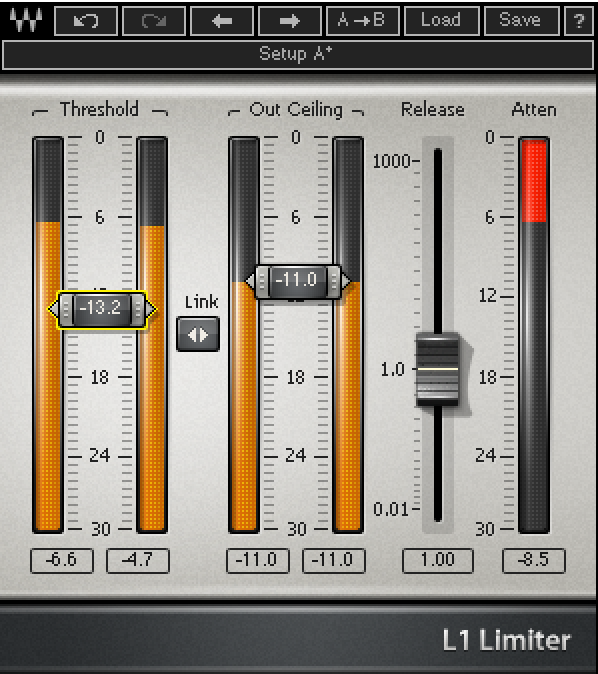

Limiters:

Limiters can be an extremely useful tool in certain situations where various elements jump out of the drum mix unnaturally.

Check out this video of Joey Sturgis demonstrating Limiting on a Drum Overhead track:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otEpP1PVPCg

Specialist “Bleed Removal”Plugins:

The past few years have seen some huge developments when it comes to easy-mode noise reduction and leakage control:

- Plugins like Sound Radix’ “Drum Leveler” and Joey Sturgis Tones’ “Tominator” offer some unique processing algorithms which allow for intuitive, next-level bleed-removal processing options.

SpectreSoundStudios’ Glenn Fricker demonstrates JST Tominator:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OGSGfArtdWM

3 – Give Them Some Color! (Saturation):

A great way of achieving thick and present drums which can punch straight through a dense mix is via the use of saturation & distortion.

Color in Sound?

You’ll often come across engineers using fancy metaphorical words such as “color” to describe various sonic characteristics. Although this terminology may come across a little weird to someone who’s just starting out, it’s actually a rather accurate definition of what it represents.

Here’s A Practical Example of “Color”:

Back in the “good-ole-days” of recording, each drum would have been captured through various layers of harmonically-rich tube, transistor and tape saturation right from the get go.

Nowadays, drums which have been recorded straight to a DAW through a linear, low-distortion digital audio interface will often end up sounding “flat” or “lifeless” as a result.

This non-linear harmonic saturation/distortion which adds pleasant warmth, depth and presence to the sound is often missing in modern-day digital recording, and what most engineers would refer to as “color” in the audio world.

Meet The Coloring Palette

Here are a few tools you can use in the digital domain in order to add some “color” to your drums:

Soundtoys Decapitator: This plugin is a personal favourite for most of my saturation/distortion needs due to the broad range of tone-shaping capabilities and utility options it offers.

The Pro Audio Files’ Matthew Weiss Demonstrates Soundtoys Decapitator on a drum track:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11Fw0U9Mbrk

Soundtoys Devil-Loc: Another excellent plugin for achieving super-crunchy, pumping drum sounds that work especially well when blended underneath your unprocessed signal.

Fabfilter Saturn: If there’s one word to describe this plugin it’s CHARACTER. The sheer amount of processing capabilities this plugin delivers gives you endless control towards forging the sounds in your head.

NOTE: It’s also well-worth scrolling through the various presets in each of the plugins mentioned above for inspiration and possible creative ideas!

The Pro Audio Files’ Matthew Weiss Demonstrates Fabfilter Saturn on a Drum Loop:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HStcVGBwTCs

4 – Make Them Huge! (Rooms):

An element that really helps define drum sounds within a specific genre is the use of ambience.

It’s not uncommon to recognise a specific drummer, band or genre just by listening to a few seconds of their isolated drum sound. Part of this phenomenon comes down to the fact that the specific rooms used while recording these tracks play a huge role in the overall drum picture.

Well known Artists and Producers discuss the famous “Sound City Drum Sound”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hfBTv5b_Cok

Dealing With Drum Room Tracks:

As you can clearly hear from the Sound City example mentioned above, a huge part of any drum sound is the room in which it was recorded. For this reason it’s paramount that you give your drum ambience the attention it deserves.

Here are a few quick ways to bring your room tracks to life:

Crush Them:

A common studio trick to achieve thick, large drum-room tracks is to crush them with a compressor:

- The most commonly used tool for this purpose is the classic UA 1176 set to stun.

- Using a fast attack & release with 10dB+ of gain reduction will help increase the room sustain of the drum shells and reduce the “peakiness” of the drum transients.

TIP: Try using the “All Buttons In” mode on an 1176 for a really over-the-top (but awesome) Drum room sound.

Blow Them Up:

Adding distortion to rooms is also a great way of giving them some extra tonal “oomph” and dense, harmonic thickness.

NOTE: Refer to section 3 for some great plugin distortion options for drums.

My personal favourite tool for this application is Soundtoys’ “Devil Loc” distortion processor:

Check out this awesome video of Mitch Thomas From Soundtoys Demonstrating Devil Loc:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cEWzT_oeZ_M

5 – Drum Frequency Guide (EQ):

A Quick Word On Additive/Reductive EQ Methodology:

It’s important to note that the EQ’ing route you choose to go down when processing will dictate whether or not you’ll need to address certain frequency bands in a specific way. Keep this information in mind when EQ’ing, as you don’t necessarily NEED to mess with EVERY SINGLE frequency band just because I’ve told you about it.

Example: If you’re boosting a lot of high and low-end then you won’t need to remove as much mid-range, and vice versa…

Here are some of the general areas to look at while EQ’ing the Drums:

Note: Take these numbers as general guidelines, not as hard and fast rules! The exact frequencies you’ll need to boost/cut will vary greatly from track to track due to the sheer amount of variables involved in the recording process. Always make sure to sweep around and fish for the areas which complement the sound best!

Drum Shells (Kick, Snare, Toms):

Note: Exactly where to focus these boosts/cuts depends on the genre of music and specific drums & mics used during recording. Make sure to experiment with your particular sounds in order to find the frequencies which work best!

Kick:

- Low-End “Thump” @ 60-80Hz: Most engineers like boosting around 60Hz for a thicker low-end, while somewhere a little higher around 80Hz can often work better for fast material with a lot of double kick content.

- High-Mid “Presence” @ 1-4kHz: Boosting the beater/stick attack somewhere within this range is vital for a present kick drum that remains audible in a dense mix. Try sweeping a bell boost around this range in context of the full mix in order to determine a good spot which cuts through nicely.

- Mid-Range “Junk” Centered @ 200Hz, 500Hz, 800Hz: These frequency areas often contain a fair amount of unnecessary content which you can afford reduce for a cleaner drum sound.

- High-End “Click” @ 8-10kHz: Boosting a healthy amount of high-end in this range usually goes a long way towards achieving a clear and “transient” drum sound. How much to boost in this range is largely dependant on the musical context. (EX: More click for death metal, less click for rock)

EQ TIP: Boosting with a bell curve will result in a tighter, more-focused sound, while a broad shelf boost will often sound “bigger” sound.

Snare:

NOTE: I won’t go into specifics for the rest of the drum shells, as the EQ concepts I’ve talked about in the “kick” section are pretty transferrable across all of them.

- Low-End “Punch” @ 150-250Hz

- High-Mid “Presence” @ 1-5kHz

- Mid-Range “Junk” Centered @ 400-500Hz, 800Hz

- High-End “Crack” @ 6-10kHz

TIP: Grammy award winning engineer Chris Lord Alge is well known for absolutely cranking an 8kHz shelf on his SSL console for individual drum mics in order to achieve his signature sounds.

Toms:

NOTE: A lot of engineers will simply buss together the individual tom mics and process them as a single group for ease. If you’re particularly picky, you can always fine-tune your EQ settings for each drum individually instead.

- Low-End “Boom” @ 80-150Hz

- High-Mid “Presence” @ 1-4kHz

- Mid-Range “Junk” Centered @ 200Hz, 500Hz, 800Hz

- High-End “Thwack/Slap” @ 6-10kHz

TIP: You can often get a pretty clear visual representation of where a specific drum’s low-end and beater/stick attack lives by viewing it on a spectrum analyser.

Check out my “Analysis As A Learning Tool” Series of URM Blogs from a few weeks back for further insight into this technique. https://urm.academy/analysis-learning-tool-part-1/

OverHeads/Cymbals:

- Low-End “Kit Content” 500Hz and Below: It’s not uncommon for the low end content below 500Hz or so to get completely rolled off in the overheads in a metal mix. Depending on the genre, you may be able to get some usable low-end out of your overheads, so don’t automatically filter them!

- Upper-Mid “Harshness” 2-4kHz: Cutting out a decent chunk of the harsh frequency content in this area can really make your overheads more listenable. This cut will also provide the added bonus of making more room for your guitars and vocals to live.

- Mid-Range “Junk” Centered @ 500Hz & 800Hz: Consider cutting some of these areas if your overheads sound “boxy” or “flat”.

- High-End “Clarity/Sheen” @8kHz+: Boosting with a gentle shelf in this area can really help towards giving the cymbals some extra sparkle and clarity. Be careful not to go overboard in this area, as this range is notoriously hard on the ears.

NOTE: A great drum EQ tool I’ve been checking out recently is the new Drumforge DF-Q plugin. This is an excellent tool when it comes to sculpting a great drum sound as it takes numbers out of the equation and forces you to really use your ears.

Watch Joel Wanasek Demonstrate DF-Q to achieve a variety of sounds:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bjd4l97XAeU

Conclusion:

Achieving great drum sounds takes a huge amount of practice, hard work and attention to detail. The main thing to keep in mind at all times while mixing drums is that each individual element is meant to fit together and form a single, cohesive unit.

Remember: Always make sure to see how things work in context of each other and the entire mix. An average listener is never going to hear your kick-direct mic in solo, so don’t bother trying to make it sound perfect in solo!

FINAL WORDS:

This concludes “Mixing Secrets – Drums”. I hope that this article has given you some new ideas to try out during your next project. Be sure to comment below if any of this information has helped you out, or if you have any questions.

Stay tuned for more production/mixing related articles in the not-so-distant future!

Thomas Brett is a producer, mixing engineer and songwriter at Brett Brothers recording studio in the UK. Check out the Brett Brothers studio website for more information and articles on all things mixing www.brettbrothersstudio.com

Read Mixing Secrets – Volume 1: Vocals here!

Read Mixing Secrets – Volume 2: Bass here!

Read Mixing Secrets – Volume 4: Guitars here!

Read Mixing Secrets – Volume 5: Synths here!

Nail The Mix is our online mixing school that gives you REAL multi-tracks from REAL bands, plus a mixing class from the producer who recorded it. Past guests include Periphery, Chelsea Grin, Machine Head and State Champs. Join now for instant access!

Nail The Mix is our online mixing school that gives you REAL multi-tracks from REAL bands, plus a mixing class from the producer who recorded it. Past guests include Periphery, Chelsea Grin, Machine Head and State Champs. Join now for instant access!

Comments 4

Pingback: [ URM BLOG ] Mixing Secrets - Volume 2: Bass

Pingback: [ URM BLOG ] Mixing Secrets - Volume 4: Guitars

Pingback: [ URM BLOG ] Mixing Secrets - Volume 1: Vocals

Pingback: [ URM BLOG ] Mixing Secrets - Volume 5: Synths