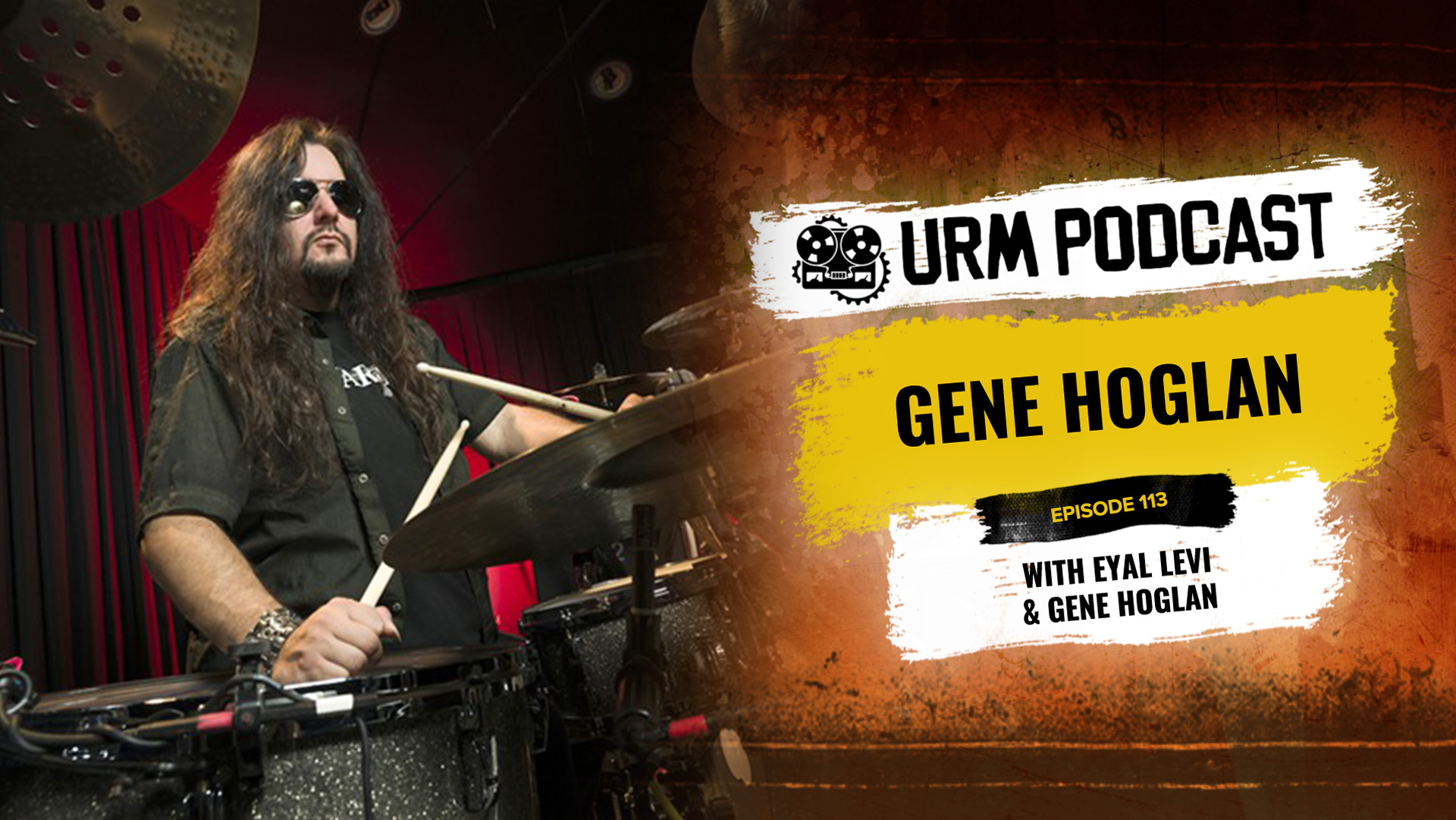

GENE HOGLAN: Learning Opeth’s Set in Hours, The Visualization Technique, Writing for Death

Finn McKenty

Gene Hoglan is a powerhouse drummer who has left his mark on numerous iconic metal bands. His career includes influential stints with Death, where he played on the seminal Individual Thought Patterns and Symbolic albums, Dark Angel, and Strapping Young Lad. Known for his incredible versatility and professionalism, he’s also been the go-to guy for bands in a pinch, having filled in on tour for Fear Factory, Testament, Opeth, and Anthrax, often learning entire complex sets with almost no notice.

In This Episode

This is a cool one. Gene breaks down the mindset that’s made him one of the most respected drummers in the game. He gets into the musicality behind his performance on Death’s Individual Thought Patterns, crediting influences like Steve Gadd and explaining how playing guitar helps him write more effective drum parts. He shares some wild stories about learning full sets for bands like Opeth and Unearth in a matter of hours, attributing it to his practice of “visualization”—a technique he uses to master songs mentally before even sitting at the kit. For you producers, he talks about what he wants from an engineer (a chill vibe), his philosophy on recording in the digital age versus the analog days, and the eternal struggle of making sure ghost notes don’t get buried in a dense mix. It’s a super insightful look into the work ethic and communication skills required to have a long, successful career in music.

Timestamps

- [5:00] The unique groove on Death’s “Individual Thought Patterns”

- [6:27] The influence of Steve Gadd and Al Di Meola on his playing

- [11:31] Why learning guitar makes you a better drum part writer

- [14:38] The importance of communication for a long session career

- [15:51] Learning Opeth’s set in just a few hours to save a tour

- [22:29] Rescuing an Unearth tour with one night of prep

- [24:35] How he uses “visualization” to learn and practice songs mentally

- [30:03] Having a relaxed attitude about making mistakes on stage

- [35:29] Recording drums in the analog era vs. the digital era

- [37:27] The pressure of running out of 2-inch tape mid-take

- [39:34] Why he insists on performing parts correctly instead of relying on editing

- [45:18] What he looks for in a producer/engineer (chill vibe, good communication)

- [48:38] Overcoming “red light fever” and the pressure of the studio

- [57:23] Chasing the Roger Taylor (Queen) drum tone

- [1:00:26] Detuning one kick drum from the other to avoid the “typewriter” sound

- [1:02:46] The eternal struggle of making ghost notes audible in a dense mix

- [1:07:33] Advice for young musicians: learn to read contracts

- [1:16:40] Why engineers love his drum setup (keeping cymbals far from toms)

- [1:28:50] The communication dynamics of working with a creative force like Devin Townsend

- [1:35:14] Why bands are more like sports teams than families

Transcript

Speaker 1 (00:00:00):

Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast, brought to you by STA Audio. Sta Audio creates zero compromise Recording gear. That is light on the wallet only. The best components are used, and each one goes through a rigorous testing process with one thing in mind, getting the best sound possible. Go to audio do com for more info. And now your hosts, Joey Sturgis, Joel Wanasek and

Speaker 2 (00:00:26):

Eyal Levi. Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast. I am Eyal Levi. Joey and Joel are not with me today because they are traveling instead of them. I've got someone way cooler anyways, so I've got one of my, I'd say most formative heroes. Mr. Gene Hoglan, thank you for being here.

Speaker 3 (00:00:47):

Hey, it's a pleasure to be here, man. I got to admit, I'm a big fan of yours, man. Oh really? I dug doth tons and liked all your work and I know we've done some touring together and that was a great time. So I'm a big fan as well.

Speaker 2 (00:00:59):

Well, thank you. That means a lot. I wasn't sure if you remembered the touring or not with us. It was a few years ago, but

Speaker 3 (00:01:07):

Absolutely.

Speaker 2 (00:01:08):

Alright, so I have a question about that, about the Fear Factory tour in Europe. Did you guys get stranded at the end?

Speaker 3 (00:01:15):

Stranded? Yes, some of us did. I remember there was a huge, what was that? There was a snowstorm. Yeah, blizzard of all blizzards over there in England, and we ran like hell over to Heathrow and then we got the turn back there. Some of the crew made it on their flights and that's good. But I think a few band members got left behind for four or five days, and I remember we had to drive to Paris to Gall Airport and got five minutes before we were boarding that plane, Paris decided to have some kind of a luggage handler strike one of those hour long strikes. And so we're like, oh, back, we've come all this way. And then we ended up getting home or flying into LAX. We landed at about midnight on Christmas morning, essentially, and I had a two hour drive home to San Diego. They didn't get me a flight home to San Diego, so I had to drive there. And then I ended up getting a flat tire on the way home. First one I'd had in years. And then amazing.

Speaker 2 (00:02:29):

I

Speaker 3 (00:02:29):

Ended up pulling into my place at about 5:30 AM on Christmas morning, and I remember my lady and myself, we were hosting a big Christmas dinner for the entire family and so slept for about an hour and got up and started cooking Turkey or something.

Speaker 2 (00:02:43):

Well, just so just for people who aren't aware of what happened, basically this was Doth was on tour with High and Fire and Fear Factory. You were playing with Fear Factory and this was winter of 2010, and it was very bad weather wise, but I guess there was this one snowstorm that took out all the airports or a lot of the airports and Heathrow got hit especially hard, and it was literally on the day that the tour was ending or the day before, basically I think 200,000 people got stranded.

Speaker 3 (00:03:18):

Holy mo.

Speaker 2 (00:03:19):

Oh yeah. They put us in a refugee tent for

Speaker 3 (00:03:23):

Refugee tent. Holy.

Speaker 2 (00:03:24):

Yeah, dude. We got to Heathrow and there was a tent city set up and they gave us the foil blankets.

Speaker 3 (00:03:32):

Oh my gosh. So you guys were essentially sleeping outside in a tent?

Speaker 2 (00:03:36):

Yeah, well, yeah, and they had cots and everything.

Speaker 3 (00:03:39):

Oh, that is psychotic.

Speaker 2 (00:03:41):

Yeah, I have pictures of it. I'll actually post pictures in the show notes for anyone that's curious. But yeah, so we got the foil blankets, normal people were flipping out on each other. It was one of those, those, I always think about this when there's a gas shortage or something and you see normal people just going crazy in the gas lines fighting each other. It was kind of one of those deals

Speaker 3 (00:04:05):

Or a zombie apocalypse or something

Speaker 2 (00:04:07):

Could

Speaker 3 (00:04:07):

Happen

Speaker 2 (00:04:08):

And you will see people. You'll see people definitely regress.

Speaker 3 (00:04:14):

Yeah. Oh my God. Yeah. That was crazy. We were fortunate enough we got placed in, there was a hotel down the way, and so we stayed for four or five days in this hotel, so gosh, it sure sounds like we got a little better shake than you guys did. That's terrible.

Speaker 2 (00:04:28):

Well, oh, well, the part that was funny about that was I guess we got so desperate being there that one flight opened up and we just got on it no matter where it was going.

Speaker 3 (00:04:40):

Yeah, sure, sure. And we

Speaker 2 (00:04:41):

Ended up in Canada.

Speaker 3 (00:04:42):

Oh Lord.

Speaker 2 (00:04:43):

Yeah, rather than Atlanta. So somehow we got to Canada and we had to explain what was happening. Eventually we rented a van to cross the border to go to Detroit Airport. Man, it was just a mess,

Speaker 3 (00:04:58):

Man. Yeah, it sounds like a mess.

Speaker 2 (00:05:00):

Let's talk music Alrightyy. One thing, and I've actually wanted to ask you this before, it was one of the things that if I ever had the chance to ask you, I would. So I have the chance and I'm going to, back in the day when I discovered you, that was on individual thought patterns and I was maybe 14 or 13 and I was first starting to get into metal or maybe I was a year into it. And I kind of thought I knew what metal drums were supposed to be, and then I heard that and your playing was so different. I mean, technically it was incredible, but it was so different. It had so much of a groove that I didn't hear in that style before. I wasn't familiar with Sean Reiner's work at that point.

Speaker 3 (00:05:53):

Fair enough.

Speaker 2 (00:05:54):

So it was my introduction to metal drumming that wasn't just, I guess double bass wasn't just thrash beats, it was pulling from many different places. And I saw that in your new DVD, Tom MCC Clark too, you talk about how you're not afraid to incorporate outside influences, and I just wanted to hear more about that, where those influences come from and how you actually go about incorporating them into your style.

Speaker 3 (00:06:27):

Well, I know that when, well, thank you very much. That's very cool. I know that around the individual thought patterns era, I had obviously grown up listening to a lot of Neil pt and for about four or five years prior to individual, I had gotten so into Aldi and especially the Steve Gadd era of Aldi Meola. And his playing was just so tasty. And it was like Neil pt, it was very, it very understandable. You could work out what he's playing. And some of it was technical, but you're like, Hey, it's not so technical that I can't figure that out like a Dave Weell or a Terry Bosio ado pattern or something. But

Speaker 2 (00:07:14):

Yeah, still music

Speaker 3 (00:07:15):

It was, and Steve Gad just, he laid everything down so tasty, such a groove, such feel to his playing. And he was kind of the guy that introduced me to the beat that is called a Bebe beat. And it's essentially just kind of a shuffling paradiddle really. But you can play that all over the kind of six eight feel. It's that was such an amazing beat. It's like that beat is directly from an Aldi Meola song called Casino. And when Chuck and I were rehearsing the record, we put individual together in about three weeks from me arriving in Florida to tracking it. And that was just kind of an approach that I wanted to do. Death was pretty well known for songs like Leprosy where they have the kick drums are just kind of doing the little double bass thing and the snares landing where it lands.

(00:08:23):

And I just thought, well, hey, why don't you try applying that Bibe beat to it? And then you can kind of use that as a jumping off point to start trying it with double rides and try it with double high hat. And I started the Bibe beat has a certain pulse to it, and you can kind of take the hand portion of that pulse and apply it to when you're just cruising with nonstop alternating kicks on the feet and it makes kind of a tasty little flavor. And there's licks on there that I could point out, well, I got this lick and individual thought patterns from YYZ, from Rush or whatever and things like that. So Chuck was very open to all of our ideas, mine, Stevie D's, and he was always very gracious, very accommodating about like, Hey, yeah, I can play my riffs over what you're playing.

(00:09:24):

I'm locking into everything, so go sick, go nuts, be creative, be you. And that was really refreshing. And I admit that when I got the call from Chuck and we were talking about getting together, I was kind of under the after hearing human. And yes, human had definitely some progressive, definitely progressive jazz fusion tendencies from Sean Reiner amazing drums on that album, A real template setter. I thought, I kind of thought that maybe Chuck and I were going to write this most psychotic death metal opus of all time. And when I got what I referred to for years as the adorable little riff tape that he sent, I was like, whoa. I was taken aback, man. I was like, wait a minute. There's no death metal on this thing. A lot of the riffs were really high up on the neck, and I play a lot of guitar and I was able to figure out the riffs pretty a lot of them anyway.

(00:10:32):

And so when I got together with Chuck, I've mentioned this before that we got together on the very first night, stopped off, had dinner at a restaurant, went back to his place and I said, Hey Chuck, let's whip out some guitars. Show me these rifts because it'll help me solidify what I'm doing on the drums. And he's showing me the riffs and I'm like, Hey, why don't we try dropping some of these riffs down the neck or up the neck, whatever you guitarists call it, and let's get 'em in the lower registers. He's like, wow, I never even thought of that cool idea. So having the riffs in my hands as well really helped kind of solidify where certain pulse points should be and certain accents should be, because there was a lot on that adorable little riff tape that I couldn't quite make out. I knew essentially what he was doing, but having the guitar in both of our hands was a real help in that. And so my influence has just absolutely ranged all over the place on that record. Totally.

Speaker 2 (00:11:31):

Well, so this podcast, normally I'd say 85% of the time, or 80% of the time, we focus on producers and production. And every once in a while we bring in musicians that we think have something to say, or maybe someone who's been on the business end of it who has great stuff to share. But one thing that we always tell the producer guys is learn as many instruments as you can because you're not going to be able to communicate with the musicians quite the same as having actually played that instrument. So for instance, yeah, I took drum lessons for six months, even though I'm definitely not a drummer of voice lessons. And so hearing you right now say that you learned the riffs on guitar, that explains so much to me that Oh, cool. Yeah, that definitely helps me understand how those drums were that musical. How many instruments do you play?

Speaker 3 (00:12:30):

I tend to play the stringed instruments besides drums. And I play guitar. I've played guitar on many, A Dark Angel record and that sort of thing. That's me playing guitar on a lot of that. And that was me when I was learning guitar. But I play bass, I've played guitar and bass on later records and stuff. It is like whatever gets the job done, really. But that's one thing, that's the reason why I learned how to play guitar because it's like I wanted to play drums. I never wanted to be a guitarist in a band. I want to be the drummer. But I always thought, well, you are going to be able to communicate your idea way better if you could directly show it to your guitarist. You can communicate to all your other musicians in your band. I sing a lot too. I've wrote pretty much the majority of the vocal lines on time does not heal.

(00:13:21):

For instance, from Dark Angel. And I've just, if you can communicate, and it's kind of like Occam's razor, the simplest way to communicate is you show them the riff rather than doing the, I don't know, the Lars Ulrich style of hum, the riff to the guy, and he's going to try to figure out what you're humming and oh, you don't have that third note, right? It's like, here, let me just show you. So that's kind of why I got stuck playing guitar on a lot of these dark angell records. A lot of my guitarists were just like, you play that, you track it, we'll learn it, but it's going to take us a while to learn that. So I have noticed, and these days there are so many drummers who are guitarists. There are so many drummers, especially in the heavier styles of music as I can listen to. I'm getting pretty good at being able to pick out albums or bands or songs where, hey, the drummer writes all this stuff. I can tell because this is not a guitarist's approach. I can tell this is a drummer's approach. And sometimes I'm able to talk to the drummer of the band and I'll ask, Hey, did you write this album? He's like, yeah, I did. I was like, I knew it. So stuff like that. So it's helpful. Definitely learn the other instruments and you can communicate very easily

Speaker 2 (00:14:38):

On the topic of communication with a career like yours that's been as long as it is. And in as many different bands that you've either been in or done sessions for, that would've been impossible unless your communication game was on point.

Speaker 3 (00:14:57):

Fair enough.

Speaker 2 (00:14:58):

I mean, I don't see how it could work unless you really know how to communicate. I just don't see any other way. So I'm wondering, say a situation like OPEC in 2005 where you guys are on tour and shit happens with the drummer and they need somebody, and I only know about that because I happen to be backstage at that show.

Speaker 1 (00:15:28):

Wow.

Speaker 2 (00:15:29):

So yeah, a strange little bit of trivia. I guess Mike was recording his parts for Rotor Runner United at my house literally on the day that their drummer made some decisions and you took over, but didn't you learn that in a day?

Speaker 3 (00:15:51):

It was like, I dunno, four hours, six hours, something like that. I recall the first show being in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and I walked into catering about noon. I was about the time. I woke up at that time and I walked in, I saw all the guys looking all really glum and just all dejected. And I sat down at their table, what's going on guys, what's happening? And they explained that we've lost Martin. We have a show in four hours, six hours. I remember it was a revolving headlining act sort of thing. So

Speaker 2 (00:16:26):

Sounds of the underground

Speaker 3 (00:16:28):

Sounds of the underground. And some days they would be the late headliner, sometimes they would be the early headliner and other headliners after them sort of thing. I think Lama, God was on that on earth, but Kymera I think was one of the other kind of revolving headliners. And at this day, OPEC was one of the earlier scheduled headliners. So we had until about four o'clock or maybe perhaps six o'clock or something. And I think they had said, Hey, I suppose you'd want to take a crack at this, would you? And I was like, sure, let's try it. Let's give it a shot. So I remember we set up Martin's drums for that, and I played Martin's drums for that gig, and he's got a pretty rather differing setup than mine. So I think we went back to my drums for all the subsequent shows.

(00:17:18):

But yeah, we sat in the back of the OPEC tour bus and I just kind of pounded pounded on a pillow and I got the discs from the guys, and it was a four song set. It was a rather short set 40 minute set or something, but that's four 10 minute songs there. And I'm always up for challenges and plus if I could help my friends out just by playing drums for 'em. Yeah, sure, no problem. So I ended up playing about 17 shows on that tour with them, and it was great. I love opec. And so that was a pretty fantastic tour. And I love strapping too, so I get to play with two of my favorite bands on the same day. That's super, super bonus for me. Yeah,

Speaker 2 (00:18:04):

Sounds pretty cool. When approaching the material and talking to them about it, did you guys have to discuss a lot of it or was it just, here's the music, good luck.

Speaker 3 (00:18:17):

It was essentially, here's the music. I think Michael, he sat with the guitar and we were going through the entire song. I listened to the music for a couple of hours and I had played one song with them, actually two songs with them previously on one night in Vancouver when they ran into a similar situation with Martin. Martin wasn't present on this tour, and he was a last minute no-show on his part. So they had their drum tech playing the easiest songs he could play, which were their ballads. So when they had come to Vancouver about a year earlier, I'd gotten the call the night before, Hey, can you learn a pick a song? Please learn it and come down and play it with us. And I remember calling Devin, I wasn't that familiar with OPEC at the time. I called Devin and said, Hey, what's a good song to play?

(00:19:10):

He's like, do the Drapery Falls. I was like, is that the one that I've heard you play before? He's like, yeah. I was like, okay, I'll play that one. And since then I had gotten into opec and I just remember I watched every one of their shows. I think it was like they played about 10 shows with Martin, and I caught every single minute of every show. So if I get the chance to hear songs get 'em in my head, then that's where the mentality of drums are 90% mental, 10% physical. If you have 'em in your brain, chances are you're going to have 'em in your hands as well. And the one thing that I was noticing a lot was when I was actually breaking the songs down, listening to 'em in the emergency situation, I'm like, okay, I know what Phil's about to come in here.

(00:20:00):

I guess I'm going to play this. And Martin plays exactly the Phil I'm thinking of. And I remember having a conversation with him a few days before he'd left the tour, and he had said that he listened to the individual thought patterns album a lot, and I was quite the influence. And so having that sort of mindset and kind of the Latin mindset towards a lot of his approaches, it made it way easier than if it was just like some crazy math metal or something that I had to really figure out. It was just there was such a natural groove, and it's like Martin on his recordings was laying down, licks that as I'm listening to him essentially breaking 'em down for the first time, I'm like, okay, well hey, he's playing the stuff I would play, so that makes it 10 times easier. So it was a challenge, and I'm always up for challenges, but there were certain roadblocks that were not present that made it an even smoother situation.

Speaker 2 (00:21:03):

So that's interesting that it sounds like your knowledge of other styles or you having other influences allowed you to pick it up a lot faster.

Speaker 3 (00:21:19):

I would suppose that that's a help, but also having an interest in their music and having an interest in them as people. It's like, because it's like if they don't figure out this situation pretty much staring at the watch in the next few hours, they're going to have to go home and it's like, Hey, let's have that not happen. It's it's easy enough to do, so let's just do it and make it happen. And I've had to do situations that are very similar. Later on in my career, I've done the same thing with anthrax, essentially on tour with testament and anthrax. And Charlie had to leave the tour and he approached me about, Hey man, can you take over for me? I was like, yeah, sure, no problem. Let's make it happen. I've got three days to learn this material piece of cake.

Speaker 2 (00:22:08):

I remember bumping into you in 2009, you rescued on an earth tour.

Speaker 3 (00:22:13):

Oh, that's right. Yeah. 2007.

Speaker 2 (00:22:15):

Oh, 2007. Yeah, you're right. That's

Speaker 3 (00:22:17):

Right.

Speaker 2 (00:22:17):

I had just toured with them in Europe and then I guess they had a blowout with their drummer or whatever,

Speaker 3 (00:22:25):

I guess. Yeah.

Speaker 2 (00:22:26):

And then you came and saved the tour. I remember that.

Speaker 3 (00:22:29):

That was another interesting situation. I was on my way from LA up to Vancouver where I was living Vancouver, Canada, and I was going back up there to do edits on my DVD at the time, my first DVD and I got a phone call from Unearths Management saying, Hey, had a situation with a drummer last night in Canada, and they've got the night off tonight, but they're playing tomorrow night in Vancouver. Can you swing in and can we get together and you play this show? I'm like, I'm willing to do it, but I'm only in Oregon right now, or I'm at the northern California area about to enter Oregon. And they said, okay, give us a minute. If you're into it, cool. Give us a minute. And they called me back a few minutes later and they said, what town are you near? And I said, I think I'm near Salem.

(00:23:19):

And they said, okay, we assume that. So we have called a Best Buy in Salem. Will you please stop by that Best Buy and pick up these two latest on Earth records and just learn them overnight. And I was like, okay, great. I've got about another 10 hours of driving to go from here, so sure, no problem. I'll stop in and I'll just give me the track listing that you guys want and I'll check out the songs. And so I did overnight and then we got together for a very brief rehearsal that afternoon, and then later that night we were playing a show and I jumped on the tour for, that was another three weeks or so of playing with them. And that was great

Speaker 2 (00:24:01):

How you just said maybe five minutes ago that it's 90% mental. There was a friend of my dad's who was a jazz drummer, his name was Harry Blazer I believe, and he played for Tina Turner and Paul Anka and then also would do these big jazz tours. And he was one of those dudes who's just phenomenal. And I remember asking him at one point, do you practice anymore? And he said, no, I don't practice. I just visualize.

Speaker 3 (00:24:33):

Yes.

Speaker 2 (00:24:33):

So you agree with that?

Speaker 3 (00:24:35):

I agree with that big time. Yeah. And you know what? I didn't even know that it was called visualization until about a month ago, and my lady was explaining, no, that's what you have been doing your whole career. It's visualization. And I'm like, oh, is that what that is? I just thought, I run over a song in my head a bunch, and I'm kind of in my head playing the drums in my head and putting all the little parts where they got to go in my head, and she's like, that's visualization. So it's like, okay, cool. But yeah, that is essentially what I do. And if your mental chops are sharp, your physical chops, even if you've taken a month off or however long it takes for your chops to degrade, your chops come back pretty quickly. But as long as you got the mental grasp of the material that you're playing, then first time you sit on a kit, no problem.

(00:25:30):

For instance, on this last little, what we just did, the 70,000 tons of metal cruise a couple of weeks ago, and they had the big all-star jam and stuff, and it was a matter of jumping on stage and playing hammer smashed face by cannibal corpse. And I never worked it out beforehand. I listened to it a few times. I got it in my head and we worked it out directly on stage and it wasn't without its butchery. And then the same thing went with metal militia from Metallica, had to do that one with a bunch of guys. There was no rehearsal, there was no sound check or anything. So it's like everybody looks at each other. It's like, okay, go follow me. I'm the conductor on this train and I'll try to keep everything within a tempo everybody's comfortable with. So let's hit it.

Speaker 2 (00:26:21):

So when you visualize stuff, do you actually go, do you imagine yourself from Gene point of view playing the drums? How does it work in your head if you could describe?

Speaker 3 (00:26:36):

I think so. I would imagine that if I'm doing it with my little invisible air, mental air drum kit, it's a lot of that. But what I do is I tap my fingers a lot. I'm always tapping, I guess my middle finger to my thumb on both hands, and that's how I am working out parts. I am doing it right now. I should probably shouldn't do that. I'm probably tapping on the mic. And I also do the same thing with my toes. I got my big toes and I'll just be playing the patterns on my toes. And my lady has walked in on me many times. I'm just here lying on the bed, eyes closed, hands across, folded across the chest, just tapping away with my fingers and my toes. And I've had roommates walk in on me. It's like, oh yeah, jean's learning songs. That's what's happening. But yeah, I guess I've got the little, the jean point of view of the drum kit and then just tapping away on the fingers and toes to work out the parts.

Speaker 2 (00:27:35):

A very, very incredible violinist. She was the concert master for the Atlanta Symphony for 20 years. She told me that before she would do a solo, meaning learn a solo concerto or something, before she knew that she was ready, she would play it from start to finish in her head.

Speaker 3 (00:27:57):

Absolutely.

Speaker 2 (00:27:57):

And if she fucked up, then she knew she wasn't ready, but she said that you're only ready when you can play it in your head without screwing up.

Speaker 3 (00:28:06):

I agree with that, absolutely. And that is the way I practiced that. Absolutely. Word for word note for note on that. Yeah, totally. You get a song in your head, and I don't read music, I don't write music. So it is just a matter of learning it by rote, I suppose, and you get that song in your head, and then when you can walk away from the iPod or the Discman or the iPhone or whatever and put everything down and then get through the song in your mind, then yeah, you've got it. And then for me, it's like, I need to do that repeatedly. If I do that once, it's like, okay, that's once, but you got to do this. Get it three times right now, especially if it's like say a long song or something, really solidify that in your head and then, okay, I'm good to have a crack on it.

(00:28:59):

And that's why planes come in handy when you're flying. Like, geez. When I started touring with Testament, I had to take over for John Tempesta who had to leave the tour to go do some work with the cult who he was also jamming with. And directly prior to the tour, I flew in from a recording session and it was like a two three hour flight to the, I think it was Dallas, where I started with Testament, and I didn't have any time to prepare beforehand, so it was a matter of having a Discman or maybe my iPhone or something. Yeah, I probably had an iPhone at the time, just checking out the songs on iTunes or something all the way to the gig, and here's your one song you get to soundcheck with, and it's a 19 song set, so at least I got to play one song at soundcheck that was helpful, but it was an onstage rehearsal that first night, and if you're prepared, you can pull it off.

(00:30:03):

And I've always said, it's just drums. It ain't brain surgery, it's music. If you make a mistake, it's going to be okay. It's not life and death. So just to have some fun with it and take all the pressure off yourself. If you play 95% of it well, and then 5%, two little parts somewhere you didn't quite get, that's okay. Probably nobody notices other than the band or yourself. So I never really get down on myself if I make a mental error on stage or anything like that, I'm pretty easygoing that way. I can usually let 'em go and not let it fester. It's like, Hey, get it next time. Just you are, just be good and get it next time.

Speaker 2 (00:30:50):

Have you always had that attitude of being easy on yourself

Speaker 3 (00:30:54):

In terms of music? Boy, that's a good question. I've always talked about my lethargy. I am a legend of lethargy. I like taking the most easiest route to any end result, and that's why usually if there's these days, if there's hauling, killing, double bass on a song, chances are that's not my idea. That's usually the guitar saying, Hey, play some hauling double bass here. I don't find, I guess it's just through experience that if you were to get down on yourself for every tiny little mistake you made, chances are nobody else notices those. I mean, people, you got to be a real dick to point out, Hey, you just played this hour and a half long show, but you made one tiny mistake. Somebody's going to be a real jerk to come up and mention that. I don't think anybody ever, other than say my friends who know my playing, and they'll come up and go, Hey, I caught that.

(00:31:52):

It's like, yeah, yeah, you're right. But I remember playing, I was playing with Testament. We were doing this song called The Persecuted Won't Forget, and it's off the Formation of Damnation Record, and that was Paul Baff playing on that. I remember Paul sitting right behind me as I'm playing this song, and I totally blew it right in front of him, and I went up to him, I was like, Hey, Paul, you saw I blew your song? He's like, yeah, but hey, whatever. So I'm like, damn, that's the one song I wanted to play. Well, and God, sure enough, I blew that, but it's something to have a laugh about and not beat yourself up too badly about it.

Speaker 2 (00:32:28):

Well, I just find it fascinating because I know so many musicians and upcoming mixers and producers too, who just live in constant mental torment over mistakes and getting better. And interestingly enough, lots of the guys that I know who have gotten really great at an instrument or production or really anything, of course, they challenge themselves and always want to get better, and they don't think that they're the hot shit, because obviously if they think they're the hot shit, they won't keep getting better, but

Speaker 3 (00:33:02):

Absolutely

Speaker 2 (00:33:02):

One thing that they share is that they don't seem to take it too hard when they have a bad day or blow a performance or something like that, just they just don't, don't take it too hard. They just keep going.

Speaker 3 (00:33:19):

That's all you can do. I mean, it's human nature to make a mistake, and gosh, if you do 999 things awesome, but you F1 thing up, it's like, gosh, you just did almost a thousand things right, and you're going to get on yourself for the one thing you did wrong. I do tend to recall those moments more than others, like the bad moments, just because I'm surrounded by so many where, well, I'm trying to word this so I don't sound like a total egomaniac, but I do. Well most of the time, and I will remember at the end of the night, oh yeah, I did blow that and I fess up to it. A lot of times Eric will come up to me, Eric Peterson will come up to me. He's like, Hey, what happened there? I was like, dude, I just gapped. I just totally gapped. And he's like, okay, I just wondering, but I'll take the blame when I'm do it, and I also will not take the blame if it's not me. I'll get down on somebody else if they're coming to me going, Hey, man, what did you do here? It's like, do you realize you fucked that up? It's like, oh, wait a minute, I did. So yeah, I stand up for myself to myself as well, I guess.

Speaker 2 (00:34:31):

So you just keep it real, basically,

Speaker 3 (00:34:33):

I guess. So if that is the term,

Speaker 2 (00:34:36):

I think so. I think that's what it sounds like to me.

Speaker 3 (00:34:38):

Awesome.

Speaker 2 (00:34:39):

So on the topic of recording, you've been in many different types of situations. I've heard a lot about what it was like recording back in the individual thought pattern days, but now we live in a whole different world. First of all, just for my dorky self, I want to hear a little bit about recording a death metal record in the early nineties, because to me, that seems to me, I feel like the modern engineers do not understand the generation that started engineering in the past 10 years, maybe or 15 years. They do not understand what you guys had to go through

Speaker 3 (00:35:20):

Fair enough

Speaker 2 (00:35:21):

To record drums back then. And so I'm wondering if it was more grueling then for you or now.

Speaker 3 (00:35:29):

Oh, I would imagine. Well, neither is that grueling other than the fact that the drummer has, he's on the hot plate at first because the session does not move forward unless the drummer gets his bits done most of the time, and even these days, jeez, you can have entire albums recorded, bring the drums in at the very end and just play to the click and everything locks up. I've done that plenty of times. But if it's one of those very organic from the ground up, we're not using clicks. We need you to nail everything on the first. You have two days to record 17 tracks or whatever a day to record 13 tracks, whatever it is. These, I'm very fortunate in the fact that I do span both approaches, and back then you just had to have your parts together. It's like the tape would cost the two inch tape that you're tracking to cost $250 per reel.

(00:36:33):

So it's not like you could do 60 takes of something and just keep hitting delete after each one and all that. But that's where you had to have your act together in terms of being prepared. And God, I remember tracking this eight and a half minute long dark angel song called The Promise of Agony, and I remember it was challenging enough to play, I suppose. But at the end of my first take, our engineer came to me, walked right into the drum room as I'm done tracking, and I'm like, fuck, I nailed it. That was great. You have one tape badass. And he just had the most dejected look on his face. He's like, man, I'm sorry. The tape ran out with about a minute to go,

Speaker 2 (00:37:26):

And

Speaker 3 (00:37:27):

I had my little freak out like, ah, how can you let this happen? What the fuck? And I got over it quickly, went in and tracked another one and got it taken care of. But just back then you had to perform. And I guess that's where I still have that work ethic involved. Now it's like, I'm ready to play the song all the way through. I'm ready to do a good job and I'm ready to make it so you don't have to create some pattern that I can't play, or something along those lines. It's like, these days I don't mind comping, I don't mind. I'll play the song six or seven times and have you pull, obviously maybe by the third take is a good bed track all the way through, and you want to pull something from take two and drop that in there and pull something from take six and drop that in there, the vibe that you are looking for, Mr.

(00:38:27):

Engineer, then I'm down for that. But I do try to perform everything that's going on the album. It's like that's me doing it, because I've been under the impression for the past 15 years or so when everything switched over to digital. It's that even though you might have kick drum stuff going on, the acoustics are going to bleed through. So whether or not that is still true, perhaps gating and things like that preclude that make that not happen anymore, it's still my mentality that I can't just play some kick drum pattern and say, oh, screw that. Let's completely change that on the record. No, I would have to play it that way because that's how I was always told. It's like, yeah, we can't really, yes, we could do a few things, move things to the left or the right a little bit, but as for completely replacing a kick drum pattern, that's going to change the whole ambience or the whole dynamic of the entire kit.

(00:39:34):

If all of a sudden we just remove whatever air is being pushed by other drums down into the kick drum mics. Like I say, I could be totally naive on that these days, but that is still a helpful approach to getting songs done the right way. It's like, I'm going to play these songs. I'm not just going to do some attempt at a double base speed, get it kind of close, then, oh, you guys just fix that later. It's like, no, I'm going to work to get that done because it's my own pride that you might grid these kicks, you might grid these drums, but it's my own pride that is making me play them the way they're going to sound on the record, I guess. So

Speaker 2 (00:40:19):

There you go. I kind of wish that more younger drummers would take that pride too. There's not that many that I've worked with who are willing to get good enough to actually play the parts, but there are a few standouts, though. I can imagine. Alex Rudger is incredible. Yeah, I've heard. Yeah, and Ry is incredible. There are some in the new generation that are just phenomenal.

Speaker 3 (00:40:49):

Excellent.

Speaker 2 (00:40:50):

But I do feel like that work ethic, those guys aside, I do feel like that work ethic is kind of missing because maybe they grew up in a time where they didn't have to

Speaker 3 (00:41:03):

Fair enough,

Speaker 2 (00:41:04):

Actually play it. Fair enough. So it's not exactly their fault, because if you didn't grow up having to do something, how would you know that you have to do it?

Speaker 3 (00:41:13):

That's fair enough. Yeah.

Speaker 2 (00:41:14):

But I do wish it was that way.

Speaker 3 (00:41:16):

Oh yeah, absolutely. Well, I try to give all drummers the benefit of the doubt because I to serious liquid metal a lot. You hear a lot of the new bands on that and you hear these psychotic drums. I try to pay attention to what's happening out there now. I try to at least have a working knowledge of most of the bands that are out there, and I'm like, Hmm. The cynic in me would want to say, well, they just tooled the hell out of this, and they just made it happen in the studio. But then I start the realist in me is like, well, a lot of these young dudes have grown up listening to a lot of guys that are psycho players, so maybe this younger generation is just killing it when they're 14, when they're 16, when they're 18. I've seen a lot of really talented, very young drummers that, okay, you're going to go places.

(00:42:14):

You've definitely got skills of a man twice your age. And so that's where I try to go with rather than just being a cynic, no, they just tooled that drummer didn't even play that stuff. They just made that in the studio. I know there's a limitation to that. I don't know these days, who knows what you can do, but I do realize that the skillset is, the bar has been raised coming out the shoot for a lot of these younger dudes. So I try to give them that benefit of the doubt. It's like, oh man, they probably just studied really hard, played really well, played along to a lot of the psycho drums out there for me, playing along to a rush song was psychotic when I was 13, but maybe there's somebody else of the newer generation that people look towards. It's like, I want to sound like that guy. And that guy actually did play his stuff, so I got to learn how to play his stuff like that. Maybe

Speaker 2 (00:43:14):

It is kind of funny. One of the, I feel like drumming, extreme metal drumming, it had a renaissance in 2005 to 2007 or something. Suddenly, I feel like right in that era, the bar suddenly went crazy and you had all these drummers that were suddenly playing insanely fast faster than before, and insanely technical stuff. And I remember talking to this one drummer who, I forget what band he was in, but I was sitting side stage and I couldn't believe what I was seeing. It's like, how are you doing this? And how did you get this good? How this seems inhuman? And what happened was that he had listened to records where the drums were totally edited and made inhuman through Pro Tools, but he didn't realize

Speaker 3 (00:44:14):

That

Speaker 2 (00:44:15):

That stuff wasn't actually played. He just figured it was real. So he learned it.

Speaker 3 (00:44:19):

And that's the benefit of the doubt that I try to give every young drummer these days. So yes, that's just it. You hear something edited, pro tooled shit and perfect sounding, and you learn that, and yeah, that's what I've been assuming is happening. And it's interesting that you were mentioning that, hey, sometimes it happens, a lot of times it doesn't. So yeah,

Speaker 2 (00:44:45):

It goes both ways. Sure, indeed. I have a question. So let's just say that you are going to the studio, and so this is something that I want producer listeners to pay attention to. Could you describe what it would be like for you, a perfect scenario, what you would expect out of the engineer? If you could give us your dream studio experience in terms of how the studio is set up and the engineer behaved, what would that be?

Speaker 3 (00:45:18):

I love a very chilled out engineer. I love an engineer that just has nothing phases him. Everything just rolls off his back. Guys like Rob Shallcross and Ulrich Wild come to mind for me in that regard. Super chill. Ulrich does our death clock albums and everything. Brendan small related, and he's great to work with because he's like, Hey, gene, you know what you're doing and you know better than I know your instrument. So it's just my job to capture what you're getting. And so all Rick is a big compar as opposed to Grider. And that's helpful for me. And just one thing that is really helpful from the band itself or whoever I'm doing the project with or the session for, is their preparation. If you have your songs ready to go or if they're not ready to go to where you and I can work on them a little bit together then and I can have my input on what might be comfortable or not for me to play.

(00:46:27):

If you're asking me to play these psychotically fast double bass patterns and okay, let me allow me to do what I need to do in order to play those patterns, put little stops, put little rests. I'm always looking, I could tack on a half hour's nap in one tiny little rest from my feet and stuff like that. But if they're prepared with their material, and I've been on both sides of the coin where a lot of times the musician is not prepared. He's in the process of writing these songs. We're doing an album together and he's got six songs together, but four of them. So sometimes they'll leave me alone with the engineers. Like this song's done. I've tracked the basic tracks for it. I've tracked scratch tracks. At least I'm going to let you guys at it while I go back to my place and work on songs seven through 10. And that's fair enough. I can get a lot of songs done that way.

(00:47:36):

I've been in every situation of studio where I've been in the super nice ones and I've been in the Super Rat SaaS ones. And as long as one thing, I like a comfortable place to when I'm not playing drums, so give me a couch that I can just stretch out on for a minute. And I like being lazy. I've spent a lot of time making myself comfortable. So if there's a comfortable situation to when there's the downtime that happens with when you're recording, computer goes down or you need to pick up this one little piece of gear, it's got to get delivered really quick before we carry on, then give me a comfortable place to chill for a minute. And I, I'm pretty easygoing in the studio, and I used to hate the studio, but now I've learned to just, it's a necessary evil, especially these days. What

Speaker 2 (00:48:36):

Did you hate about it?

Speaker 3 (00:48:38):

So much pressure on the drummer that we cannot carry this session forward unless the drummer gets his job done first off, right off the bat. And when I was younger, that was a lot of pressure for me. But that's where it's like each album that I did, the red light fever would go away because I would get red light fever as much as anybody else, especially my early albums. It's like, oh shit, now I'm recording Jesus. And so I guess as time's gone on, actually, if I'm really familiar with the material, say a lot of strapping albums, we've rehearsed a lot for especially the last two or three records. So I was really confident with the material. So I would kind of take the kind of Bernard Purdy sort of approach, and it's like, be super cocky, awesome. I'm going to nail this. We're going to kill all these songs. They're going to be great. We're going to get great drums. It's going to be awesome. I would just go, and that would be the only time I would ever let myself get, I guess, cocky or

Speaker 2 (00:49:43):

Just, but that's useful. That's a very useful time to get cocky.

Speaker 3 (00:49:48):

Yeah. If you're a quarterback, you don't want to go into the game going, oh man, I don't know if I'm good enough to do this. I don't know if I could throw the touchdown pass when we need it. It's like, yes, I can give me the ball. I'm ready to do it. That's the attitude I would take, and that kind of got me over my dread or fear of that red light.

Speaker 2 (00:50:06):

So it was a mental thing for you. It wasn't anything really that the producer said or did. It was an internal battle that you won?

Speaker 3 (00:50:16):

Pretty much. Most producers I've worked with, I don't think I've ever, ever worked with an absolute dick where it's like, I can't relate to this guy at all. And especially these days, because most engineers, they know who they're bringing in and they understand that, okay, this guy might have an approach that works for him, and let me just kind of study Gene for a minute and see what works for him, and then try to be amenable to his attitude in the studio. And Oh, hey, he's got a pretty decent attitude in the studio. Okay, this is going to be great. So I do like an engineer that is forthcoming with the information, you're doing a good job. Or Actually, I need a little more this. You need to lean into every beat. A little bit of direction is helpful, but I find that a lot of engineers are like, gee knows what he's doing.

(00:51:11):

Leave him alone. He knows what he's doing. And if that's the approach, it's like, okay, let me take over, but then I don't want to hear any complaints afterwards. It's like if you're letting me, and I'm a pretty decent self producer, self what editor or whatever, if I nailed a part, I'll say I nailed that one. And if I didn't, I'll be like, Hey, let me do another take. I got a better one in me. I'm pretty decent in that regard, even though I'm lazy. It's still, you have your, I guess, your own integrity. You don't want to give like, oh, I gave that 80%, but I know they'll fix that in editing later. No, you want to give a hundred percent because you have to look at yourself in the mirror every morning, and you have to know that, yes, that was beyond that record. I did kill it. I did a good job. Whatever they do from here on out with the project is their prerogative. But you laid down the best humanly possible drums you could. So

Speaker 2 (00:52:09):

Yay. In my opinion, one of the signs of a good producer or a mature producer is knowing when to get out of the artist's way. So there's some artists where artists musicians same thing where you should just let them do their thing because there's a reason that they got hired, and it's because of their thing. But then at the same time, you have to have the confidence as a producer or engineer to know when, even if the guy is really good at doing his own thing, maybe you need to help him out with a suggestion or something. Or maybe you need to see the line of when it's okay, when it's helpful to speak up when it's not understand it and walk it. I think that's one of the markers of a good producer. Something that's interesting, and this stuck with me for a while. Did you ever know Shannon Lucas, the old drummer from a Black Dahlia murder?

Speaker 3 (00:53:11):

Yeah. Yeah, I did. Yeah, we did. He was touring with somebody else.

Speaker 2 (00:53:15):

Yeah, he's been in a few bands.

Speaker 3 (00:53:17):

Yeah, but I don't, Shannon, absolutely

Speaker 2 (00:53:20):

Big Earl Lobes. Yes. And he's a big Earl Lobes and phenomenal player.

Speaker 3 (00:53:26):

Absolutely player,

Speaker 2 (00:53:27):

Totally on the Battle cross record a few years ago. He is one of those players that insists on it being him and on playing. Oh,

Speaker 3 (00:53:40):

That's great. All the

Speaker 2 (00:53:41):

Way Throughly. He's the real deal. And he was so badass that I basically just let him do his thing, and then he got kind of mad at me for not pushing him harder. Oh, wow. But I was thinking, you don't need to be pushed harder. These takes are incredible. That's

Speaker 3 (00:53:59):

Great. Yeah, absolutely.

Speaker 2 (00:54:01):

So I've had that backfire on me before, but I still stand by it not having pushed him harder. He didn't need it. He was phenomenal.

Speaker 3 (00:54:12):

Yeah, and that's great. Like you said, that's definitely a fine line, and it sounds like you walked up pretty well. So nice work.

Speaker 2 (00:54:20):

The takes were great, but it's just interesting. One thing that I've found is hard to get over but important to get over is sometimes I feel like people have to feel like they are doing something productive rather than actually doing something productive, if that makes sense. So maybe we didn't work as hard as we should have because you didn't say anything. But then again, did we really need to say anything if it was already perfect?

Speaker 3 (00:54:56):

No, I hear what you're saying there. Yeah. And absolutely that's a fine line, but it's okay as long as it is productive. And that's one thing with strapping, every album we recorded, every live show we ever played, I really felt like this is going to change somebody's life. This album will change probably a few people's lives. Our live show, somebody's life is going to be changed tonight. They're going to come up afterwards and go, oh my God, I know what I want to do with my life. I know what I want to do with my music. And so if you go into a project with that in mind that you're going to change lives, it's like that's a lot of responsibility that you put on yourself. But hey, that's just one more challenge to have. And that's why a good musician will push themselves. They want that to be them.

(00:55:49):

They want that to be true representation of where they're at at that time. Maybe in 10 years they're going to be way more advanced, but hey, this is the best I have right now, and I'm giving you my absolute best. So that's one way that I've always wanted to just leave a project behind. It's like, Hey, I gave you my absolute all and I'm proud of what I did, so whatever you guys want to do with it, that's your prerogative. But I'm ready to walk on from this. And with my head held high sort of thing, I don't think I've ever come out of a record where I'm like, oh man, I just botched that entire thing. I don't think so at all. So there you go.

Speaker 2 (00:56:27):

Great. Well, before we wrap up, I've got a few questions here from our audience if you don't mind answering them. Sure. They were stoked that we brought you on, as am I. So here's, there's quite a few. I'm looking for ones that we didn't already cover.

Speaker 3 (00:56:49):

Okie doke.

Speaker 2 (00:56:50):

So here's one from Adam Castle, and it's kind of long. What do you look for in a drum tone slash sound versus the arrangement of the song and the pars you play? I've always loved gene's playing and sound and think his tastefulness is often overlooked for this insane skill and monster sound In many ways. He reminds me of Roger Taylor from Queen, that big beat sound with real groove and taste and power. Also, gene is proof that wood beaters are superior darn tootin.

Speaker 3 (00:57:23):

Well, I guess I look, when it comes to say how the drums are going to be presented on record, I just try to give as much of my tone as I can. We try to tune the drums per project. Like some projects, I tune the drums up a little bit more. Other times I like them kind of low. And I like that Roger Taylor has one of the greatest drum sounds ever. Roy Thomas Baker was just an absolute genius with his drum tones. And yeah, I try to achieve the Roger Taylor drum tone. That's very cool that he pointed that out. Oh, good ear. Yeah, absolutely. And I guess the thing, because these days with all the sound replacing that goes on, it's like, okay, well, I usually try to have a pretty decent kit. I don't think I've had to sound replace much over time. Perhaps that's something I might not even know about.

(00:58:20):

But if I do sound replace, I try to do the one hits beforehand of my own drums. So give you a lot of clarity. If you have to replace something, then at least you've got my own drums to do it with. And I remember a session, the session that I did right before I joined that testament tour in progress. I remember that kit was not the best sounding kit. They might've sound replaced it, but I did try to tune it as good as possible. The thing I look for these days is clarity. More than anything, the tones are going to be whatever they are. I try to give a good tone to tape, but it's a matter of when it comes down to the mix, that that's where it's really important. And I'm all about the clarity. And sometimes I work in rooms that aren't the largest drum room around, but the engineer knows his room, he knows what to do with it and maximize whatever sonic qualities that tiny closet of a room might have.

(00:59:25):

So I guess when it comes to mixing, I love being involved in mixes many times I'm not, but I love it when I am involved because for instance, something like we used to do with strapping is I didn't want two kick drums that sounded the exact same. Yes, we multi-layered the triggers on strapping records. Hey, we used them a sugar kick from Destroy a Race and prove on City. Devin actually yanked the file from Toma Coburg the engineer, or Toma Sandstrom I think is who we used, yeah, they were doing a project together and he was able to find Tomas, destroy, erase, improve kick drum, and he just yanked it and that was one of the ones that we blended. We tended to use a blend,

Speaker 2 (01:00:24):

Yo, that's a good word.

Speaker 3 (01:00:26):

Yeah. So that happened, but one thing we try to do is we try to, I like to detune my right kick from my left kick. Even if we're using triggers and samples and replacements and all that sort of stuff. I still don't, I'm not a big fan of that machine gun. Both kicks sound the exact same typewriter. Yeah, I'm not super into that. So I know Fear Factory, they had their approach. They liked that, and so those kicks were, they wanted the drums to sound like a machine. I understand all that, but if I have my druthers, then I'm all about let's de-tune the right kick from the left. I like the left one to be just a semitone higher than the right. So we'll usually work with the acoustics and that's why I like to blend the acoustics in, tune them as close as possible, but just let both acoustics have their own dynamics and so it's not just, it's a little bit of just a little breath and bounce to it.

(01:01:33):

That's one thing we always tried with strapping and I'm not afraid to take a pulse point right on the top of every bar and just add just the tiniest stick of volume to a pulse somewhere in the middle of all of it. I like doing that and just to give the drums a little bit more dynamics in this age of digital perfection. Just try to give something a little bit of dynamics. So I mean, that was a really cool question, but yeah, I guess the clarity is the most important thing for me. Just I play the drums, you might as well hear 'em. I'm more concerned with the clarity of them than feel free to back off on the Tom tone if that's affecting the clarity or I like the symbols to come through and there's many a time when I'm like, oh man, I'm not really into the symbol tone that this final prod product is, but what can you do? There's going to be another record somewhere. We're going to record something somewhere else, so get it right on the next one.

Speaker 2 (01:02:37):

Well, you have a lot of nuance in your playing, so I can imagine that it's frustrating if that gets lost in the mix.

Speaker 3 (01:02:46):

The one thing that gets lost all the time on every one of my records, it never comes. This is something I would love to improve is the ghost notes that I pointed the I knew you

Speaker 2 (01:02:58):

Were going to say that. I knew you were going to say that. I was just going to say, we actually have spent a lot of time showing people how to mix those properly because they get lost. That's the number one thing that the good drummers complain about with mixes when working with them. They always say that on their previous records. That's the one thing that they hate is that they're all lost or

Speaker 3 (01:03:26):

Yes, absolutely. And so I've tried to put more of an attack on the ghost notes, but then that's not a ghost note. If you're leveling up your attack of a ghost, then that's not the natural feel that you're getting. The one thing that I try to do is if it's something that's really important to me is because a lot of times if you've got the multis sampled snare going, I try to stay away from that too, but I understand that engineers will add little nuances to make it the clarity of it, and I get that a lot of times if you hit the ghost notes too hard or you try to ghost note the samples, it just sounds like this digital, just this horrible sound. So it's like, okay, well maybe anywhere I'm hitting a ghost note, just let the acoustic drum boost the ghost note in, mix on the acoustic drum and then it'll sound more natural.

(01:04:26):

It just won't sound like a, or whatever the ghost note is, it sounds like a little brushy, little ghost note. Just raise the volume of it. And these days, the guitars are so loud and they're so overdriven and all that sort of stuff that I know going into some projects, if you have ghost notes on this, they're not going to come out and it's like you just give into it and just go, okay, well maybe somebody ever catches me playing these songs live, which has happened many times with strapping stuff. We lost all ghost notes with strapping and people would be on the side of the stage watching, especially on those sounds of the underground tours and the Oz Fest where you got a lot of people hanging around behind the set or whatever. They'd be like, I had no idea you were doing all that with your snare, because all I ever hear is just a bap, bap, bap, bap, bap. It's like, well, indeed, we're not to the point where we know how to get a ghost note through a mix these days, but hey, we're going to work on that.

Speaker 2 (01:05:27):

I'm going to send you just some videos that we've made about that topic just because there are a lot of the techniques for making them stand out, I feel like are stuff that just some guys have figured out in the past few months or past year because yeah, it's, I mean, if I feel like it's something that engineers should have focused on earlier because drummers have been complaining about this for years. Fair enough. But I guess a lot of the metal guys, a lot of the metal mixers, their priority has always been the sickest guitar tone, the biggest snare tone, stuff like that. And then once you get past all these priorities, certain things like ghost notes, they didn't get the attention that they deserved because they weren't the priority. While there were so many other things that were, I guess super highly competitive between mixed engineers,

Speaker 3 (01:06:37):

Absolutely. I can see that

Speaker 2 (01:06:38):

They're all fighting for the sickest guitar tone and they forget the ghost notes. So yeah, I'll send you a few videos that we've made because there are some ways to get around it or to bring them out in the mix more just not many guys are doing it, but I think they might start to. So there is hope. Excellent. Hey, we love that. We love hope. Yeah, hope does not die today. So here's a question from Sasha Vino, which is you come from a time where it was more obvious about how to make a living from music. If you rule, you go make an album and you go play some tours. No, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook marketing, anything with all this shifting in our economy, what are the three Don't do that. You would absolutely tell up and coming people.

Speaker 3 (01:07:33):

Well, let me start with some of the try this or try that is to kind of figure out with some of this economy is I would imagine I never did this, but I wish I did. I had to learn from the school of hard knocks on this one, but learn how to read a contract. I'm really good with reading legalese now, it's not that challenging, but a lot of times when you get, especially back in the day when your contract was this big two inch thick dossier or whatever, I taught myself legalese and it's not all that challenging, but learn how to read what you are about to sign. It's one thing because I mean, back in the day we would hire a lawyer, and I remember Dark Angel had Prince's lawyer, but when he's working with guys like Prince and people of that caliber, the tiny little thrash metal band is not going to get a lot of pouring over their deal.

(01:08:43):

So we signed contracts that lawyers looked over and we ended up getting screwed. So early on I was like, man, I'm not going to let this happen anymore. So I've learned how to read contracts. That's something to try maybe perhaps take a business course just so you know how to even manage your money, I suppose. I never did that either. Never went to college, but I would imagine that that couldn't hurt in this economy these days. It's like when the file sharing started happening and the illegal downloads and all that. Yes, that has changed our economy drastically, our musical economy. I don't think a lot of times that was very young people doing that, taking advantage of the new technology where they could do that and why would I buy this when I can get it for free Now I can listen to a thousand bands as opposed to 10 that I could afford to buy.

(01:09:46):

I understand people want the shortest route to pleasure, I suppose. But one thing I don't think anybody thought about is that, okay, guys of my age, my experience, we are feeling that crunch because this is the time when you want to be able to enjoy the fruits of your labor. You want to be able to record a record, put it out, make a nice living from that album because that's what we were taught when I was young. I was taught this is what's going to happen for you, and that really isn't the case anymore. But a lot of the young folks that helped design this path that we are on now, they're in that situation where, Hey, at least I got to see some album royalties. I got to sell a hundred thousand records of something and make some cash off that you guys, you could have a hundred thousand downloads and never see a dime from it. And

Speaker 2 (01:10:50):

You got some of the getin while the getin was good

Speaker 3 (01:10:53):

Indeed. And now a lot of the young dudes out there, it's like, this is the template that you created for yourselves. I'd love to see how you worked yourselves out of this. They're trying with all the social medias and stuff, but that's all great advertisement, but I am not aware enough of social media's impact on income. I'm just learning how to monetize things on social media, on YouTubes and that sort of thing. But maybe these young kids are becoming masters of that, but it's like, Hey, you youngins, you created this for yourselves. You made this bed and I fortunately have been able to make some money off some earlier projects. Do a little bit here and there, make a little cash here and there. You now don't have that aspect to this available to you. So I know you got to figure out some other way to make some cash and I didn't do this. You did. So you figure it out. Young dudes, for those who like to steal files and all that, it's like you like God, I'm in that boat right now. I've got my new DVD that just came out and the climate has changed.

(01:12:14):

Why purchase a physical copy of A DVD when you could go on some Torrent site and just watch it for free? I understand the lethargy involved. I get it, but there's not some mindless corporation that put up money for this DVD for me to make it and distribute it. It's all my money. I put my own cash into it. I do this and

Speaker 2 (01:12:40):

It looks great, by the way.

Speaker 3 (01:12:41):

Oh, thank you very much. I don't take money from say, my sponsors. I don't have pearl breathing down my neck saying, Hey, you got to do something like this or SBE and telling me, well, you should do it like this. Not that they necessarily would to begin with, but IX out that possibility by doing it on my own dime, and it is me who either reaps the benefit or suffers from lack of interest in purchasing it. If people can go to a Torrent site and download it, then I understand why they would do that. It's like, fuck, I don't want to buy this thing, but I do want to see it, so I'll go find some Torrent site and download it. And it never seems to matter to people what they are doing to others with that philosophy. And so, hey, life's tough. Get a helmet.

(01:13:46):

We'll work our way around it. We'll figure it out These days you record an album and that's just a demo to be able to go out and play shows, sell merch. That's how you make your money. It's pretty well known these days. That's how you make any money. But even t-shirts, those aren't free. If you want a quality shirt that's going to sell and not just some one colored rat's ass $6 shirt, you want to have a quality shirt that's going to cost you two. So where do you get that capital? So it's this kind of like this Ara Boris snake that just keeps eating its own tail and every once in a while a little stop chomping on itself enough to let somebody take advantage of some aspect. And we are all figuring that out. There is a new template coming and I'm not sure what it is, but there's bound to be.

(01:14:46):

So right now, musicians of my ilk my age are, we're adapting in the best way we know how. And that's where, okay, you put out this demo, your brand new album that used to be the thing you were looking for. Now you just kind of put that out in order to open up the avenues of touring and merch selling, and that makes it a lot more complicated if you don't have income from the thing you spend your six months working on and then it's not going to provide an income for you, man. Jesus, thank you, youngins.

Speaker 2 (01:15:23):

Yeah, that definitely is totally different that now the album is the advertisement for everything else.

Speaker 3 (01:15:31):

Absolutely. People don't even buy the new records. I mean, obviously you could put out this killer badass, God, this is Us at the top of our game and people are still like, oh, we just want to hear songs from the first two or three records. That's when you guys were good. Okay, whatever.

Speaker 2 (01:15:51):

I'm sure you get sick of that one.

Speaker 3 (01:15:52):

Hey, I'm always down, especially if it's an album that I performed on. Yeah, I want to play songs off like the New Testament record. Yeah, I want to play a bunch of songs off the new album. Yeah, I want to play songs off of that. The entertaining records, I'm sure. I don't know how the guys feel about, oh, having a trot out boy into the pit for the thousandth time or over the wall or disciples of the watch or whatever. But hey, if that's what your fan base is there to hear and they're still going to buy a t-shirt on the way out, then hey, that's the best you can do.

Speaker 2 (01:16:31):

Totally. Here's one from Mark Sten Hagen, which is how do you react when the producer asks you to move your symbols in your setup?

Speaker 3 (01:16:40):

I am very fortunate is that I learned at an early age keep your symbols very far away from your Toms. So I've never had that issue happen. Great. I have a pretty wide, there's a good foot, foot and a half between every symbol and every Tom. So I know a lot of drum kits have boy symbols are right on top of those Toms and I can see where an engineer is going to be like, Hey, man, you're getting a lot of bleed. We can't have that. But that's just my natural initial setup was okay, symbols way up high and far away from drums, and I've never had that issue ever happen.

Speaker 2 (01:17:20):

Well, I've always told drummers man, that when they come in and they want on organic sound with minimal replacement, but then they have their symbols like an inch off of the Toms, it's like, dude, if you actually want what you say you want, you're going to have to work with me on this and raise those symbols. You're tying my hands behind my back.

Speaker 3 (01:17:39):

Absolutely. So I've had engineers look at my setup, come in, look at the setup and go, oh God, thank God. Oh cool, thank you,

Speaker 2 (01:17:48):

Dude. That's the moment you see a drummer set up like that. The feeling that you get is gratitude, pure gratitude.

Speaker 3 (01:17:57):

Awesome.

Speaker 2 (01:17:58):

So here's one from Anthony Ante, which is you spoke in death clock interviews about fleshing out a song for a day to make it seem like you've spent months refining a song. Do you have any advice about how to keep yourself and your band mates focused and positive when you're doing these long sessions?

Speaker 3 (01:18:16):

Well, lemme clarify that. Working out, fleshing out a death clock song in a couple of hours, getting a day on a death clock song, I'm like, wait, what? When did that ever happen? No, we get a couple hours a piece. I still have to track the thing over a couple of hours too, and we've got another one to do after this. So we got to get a couple songs done at least, and if they're short, then we got to get three or four done a day. But you know what, that is just a little bit of self policing. If you have just a limited amount of time and say you're on the clock or something, you got to figure it out. You got to figure out this arrangement. Then I would just suggest surround yourself with musicians that are of mind. And that's one thing I've told people is find musicians. Maybe they're not the best musicians in town, but if they share your focus, they share your vision. You got to be with guys in your band that you can hang with. And if you all share the same musical vision, like yes, we want to achieve something and we are willing to work to do it, this is a job.

(01:19:46):

It's a great job, it's a fun job, it's a very creative job. But if you approach this as a job, like Devon Townsend, he's the master of this, and he's told me back in the day, he's like, well, you figure this is a job. If you approach this like a job and you spent 10 hours a day at your job, you're going to be successful at it with Devin and with musicians. Sometimes that's a 16 hour day, but if you approach it like, I'm getting good work done here and tomorrow I'm going to get up and do more work, that's a helpful attitude to have. And if you have to whip your band mates into shape in terms of focus, then I used to have to do that with Dark Angel. I was a real task master. I ran the whole show there for the last couple of years, and you just try to find people that are willing to self-police their own focus. You find that those musicians that are like, yeah, I want this to work. I want this song to be badass. So yeah, I could be texting my girl for the next half hour, or I could be in here working on this song, or I could be out at the bar next door tossing back a few, or I could be in here working on this song. You want to find the guys that are like, Hey, I know when to prioritize. Let's work on this song and then we'll hit the bar afterwards.

Speaker 2 (01:21:23):

In my most successful collaborations, and I don't just mean musical mean business partners as well, just anything that's never been an issue. The guys that I've gotten the best results out of life with, I've always, always just naturally focused on the task that needed to be completed. It was always my rougher situations where I had to police people. And those tend to be the situations where you don't have as many minds going for it so you don't end up with as good of a final outcome, I guess.

Speaker 3 (01:22:06):

Absolutely. I could see where it could only take one tiny question session with yourself of why am I doing this with these guys? If you have to ask that, then sometimes it's, oh shit, you've already lost it. It's like you want that little self moment with yourself to be like, man, I love doing this with these guys. Everybody's got a good mindset about this and we're getting stuff done. Yes,

Speaker 2 (01:22:31):

Man.

Speaker 3 (01:22:31):

I've been

Speaker 2 (01:22:32):

On both ends of that and man, it's so much better when you can have the positive version.

Speaker 3 (01:22:38):

Absolutely. I have too. And I like the positive do.

Speaker 2 (01:22:40):

Yeah, yeah, definitely. So here's one from Eric Burt. How and why did you start playing? What are the benefits you found to playing this way?

Speaker 3 (01:22:48):

Well, the reason I started playing open-handed was merely where my record player was located when I was a kid, it was on like say if you're lying down on your bed staring at the ceiling, it would be on the left side. So as you're sitting on the corner of your bed up at the top by the headboard, that's where my record player was located. So if you're sitting on your bed playing along with your favorite stuff, playing on your bed, if you notice I'm playing, as you're sitting on the bed, you're playing in the top right corner of the bed at the top corner is kind of the snare. As you get towards the middle, it goes lower. You got more beef in the center of your bed. So record player was on the right side of my bed there. So I'd switch a record play on it, and the snare sound is kind of the top corner, the highest, and the kick drum sound is kind of in the center.

(01:23:56):