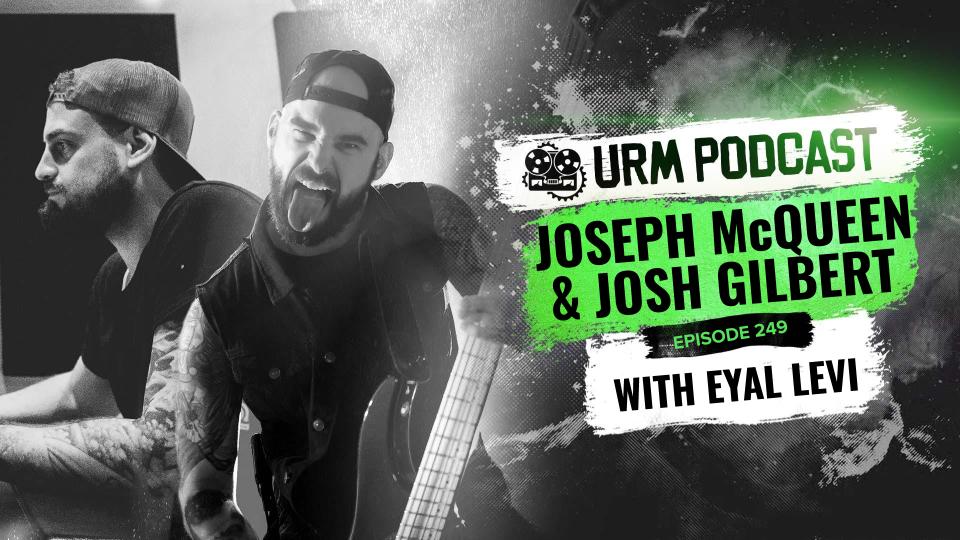

Joseph McQueen & Josh Gilbert: Producing As I Lay Dying, overcoming imposter syndrome, and building a career

Eyal Levi

Production duo Joseph McQueen and Josh Gilbert go way back, having met in the local Birmingham, Alabama metal scene in the early 2000s. Recognizing a shared, serious drive, they played in bands together before Josh landed the gig as bassist and clean vocalist for As I Lay Dying. After years of touring and honing their individual skills, they reunited in Los Angeles to form a production team. Together, they’ve produced, engineered, and mixed a number of high-profile artists, including Bad Wolves, Light the Torch, and Upon a Burning Body, culminating in their work on As I Lay Dying’s acclaimed comeback album, Shaped by Fire.

In This Episode

Joseph and Josh drop in to share their story of going from local scene grinders to an in-demand LA production team. They get into the psychology of being a producer, talking about how to overcome imposter syndrome, embrace failure as a learning tool, and build trust with artists—even when you’re butting heads. They also offer some real-world business advice, stressing the importance of setting clear client expectations to avoid burnout and the trap of overbooking yourself when you first start finding success. The guys share some incredible stories, from using the AILD tour bus as a moving truck to Joseph finishing the Shaped by Fire mixes just days after a near-death surgery. It’s a super honest look at the mindset, work ethic, and relationships it takes to build a sustainable career in music production.

Products Mentioned

- Antares Auto-Tune

- Synchro Arts VocAlign

- Waves Smack Attack

- GetGood Drums

- Tech 21 SansAmp RBI

- Ampeg SVT Classic

- Ampeg SVT-4 PRO

- Peavey 6505

- Aguilar DB 410 Cabs

- Fender Geddy Lee Jazz Bass

- Ludwig Black Beauty Snare

- Apple AirPods

Timestamps

- [2:04] How Joseph and Josh first connected in the Birmingham, AL music scene

- [5:00] How Joseph ended up recording Josh’s tryout for As I Lay Dying

- [10:25] How the As I Lay Dying hiatus pushed Josh to really learn recording

- [17:18] Debunking the myth that LA is oversaturated for producers

- [20:33] Using the As I Lay Dying tour bus to move their studio gear to LA

- [27:22] Getting their first big gig mixing a Suicide Silence live DVD

- [35:32] Learning to overcome introversion to network at big festivals

- [44:17] How to use imposter syndrome as a tool for motivation

- [51:23] Learning to embrace failure as a necessary part of growth

- [1:00:34] Their policy on handling mix notes and revisions from clients

- [1:06:42] Why you have to define expectations with bands upfront

- [1:10:44] The trap of overbooking yourself when you first start getting successful

- [1:20:06] The science of why sleep deprivation can sometimes boost creativity

- [1:28:19] Joseph’s near-death health scare in the middle of finishing the AILD record

- [1:33:20] How Joseph mixed through hearing loss after his emergency surgery

- [1:42:51] Competing against Colin Richardson to mix the new As I Lay Dying album

- [2:02:13] Joseph’s vocal production method for getting confident, passionate takes

- [2:33:55] A deep dive into the 5-channel bass tone on the album *Awakened*

- [2:38:40] Breaking down the huge snare sound on “Shaped by Fire”

Transcript

Speaker 1 (00:00:00):

Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast. And now your host, Eyal Levi. Welcome to the URM podcast. I am Eyal Levi, and I just want to tell you that this show is brought to you by URM Academy, the world's best education for rock and metal producers. Every month on Nail the Mix, we bring you one of the world's best producers to mix a song from scratch, from artists like Lama God Shuga, periphery A Day To Remember. Bring me the Horizon, Opeth many, many more, and we give you the raw multi-track so you can mix along. You'll also get access to Mix Lab, our collection of bite-sized mixing tutorials and Portfolio Builder, which are pro quality multitracks that are cleared for use in your portfolio. You can find out [email protected]. So Joseph McQueen and Josh Gilbert, welcome to the podcast.

Speaker 2 (00:00:47):

Thank you.

Speaker 1 (00:00:47):

Thanks for being here.

Speaker 2 (00:00:48):

Hey, how's it going? No problem.

Speaker 1 (00:00:49):

It's going good. I'm glad that we caught up. This is very interesting to me because first of all, Josh, I had no idea you were even in URM and Joseph. I feel like I'm going to just be really, really honest here. I hadn't heard of you until you came up in our group, but then when I heard your work, I was like, why don't I know who this dude is? And I started researching it and was like, wow, he's done a lot of stuff. I'm glad I got introduced to you and

Speaker 2 (00:01:27):

Oh yeah, that's great.

Speaker 1 (00:01:28):

Yeah, and it was just, the whole thing was just kind of a pleasant surprise I think. I don't normally hear about people that much anymore. I feel like due to what I do, I kind of hear about people on my own before most people would, and you just kind of flew under my radar and now I feel like a bit of an asshole about it, but I love your work,

Speaker 2 (00:01:57):

I appreciate

Speaker 1 (00:01:58):

It and I love your guys' work together. And so if I'm understanding this correctly, you guys actually go back a long way?

Speaker 2 (00:02:04):

Oh yeah, yeah, super long way. We've actually been friends since around 2004, back when we were both just doing the whole local band thing in Birmingham, Alabama, and we just kind of started clicking really early on and joined a metal band, or we started a metal band together with a few of the other powerhouse dudes, I guess, around the area.

Speaker 3 (00:02:30):

Yeah, I think the reason me and Joseph clicked so well is because we recognized each other as sort of the only other dudes who actually took it super seriously in the area that cared about gear. Yeah,

Speaker 1 (00:02:42):

That whole attract kind of thing.

Speaker 2 (00:02:44):

Right. And we both kind of had the producer mentality already before we even knew that's what we wanted to do in a band, if that makes any sense. We were less on the creative side and more kind of trying to oversee everything and that whole deal,

Speaker 1 (00:02:59):

Man, those days, 2004 days, that's when my band was a local band in Atlanta, and I know that Atlanta is more of a, I guess, cosmopolitan city than the ones you find in Alabama.

Speaker 4 (00:03:15):

Definitely.

Speaker 1 (00:03:17):

But Atlanta, even Atlanta back then was a bit of a wasteland, and so I always felt like when I found people that I felt like were serious, I clung onto them really, really hard. It was so easy to spot. I imagine that it was like diamond in the rough status out in Birmingham.

Speaker 2 (00:03:42):

Well, we actually had a pretty strong circle of friends, but yeah, I mean within that it was very clear who the ones that we wanted to team up with, they kind of stood out from the pack.

Speaker 1 (00:03:56):

So did you guys ever foreshadow that it would be a decade and a half later and you'd be partners?

Speaker 3 (00:04:02):

Not at all. No,

Speaker 2 (00:04:04):

Definitely not

Speaker 3 (00:04:04):

At that point. I think the main goal was just let's rent a VFW hall and put on a show this weekend and try to sound like the best band there out of our five friends bands that were going to be on the show.

Speaker 2 (00:04:18):

Got it. Totally different aspirations at that time.

Speaker 1 (00:04:21):

Josh, when you joined as dying, was that the destruction of the band you guys had together and your working relationship up to that point? What happened then?

Speaker 3 (00:04:36):

Not exactly. What had kind of happened at that point is Joseph and I had been there for the rise and fall of several of our bands and we would be the last two members still dedicated, and we were out slinging pizzas to be able to afford to buy guitar strings and go play shows in a smoothie shop parking lot that we used to play at all the time or wherever, places holding the walls that you can find. And at that point, it was one of the downtimes where a couple of the guys in our band, they'd either gone off to college or their girlfriend had told 'em they needed to spend more time on school or whatever. I don't know, but it was one of those off times and the way that it actually came together was that the band that we had last been working on had sent a demo to Tim who was doing an imprint under metal blade at the time, and that demo was actually one of the first things we recorded. So even as far back as that, Joseph was kind of instrumental in recording our band, recording me, and ultimately recording my tryout for Esle dying.

Speaker 1 (00:05:43):

I see. So when you got the gig, was it just like High five? One of us made it out, I'll make it out next.

Speaker 2 (00:05:50):

Yeah, totally. I mean, it was obviously bittersweet for me because he was my best friend and he was instantly moving across the country, but it was so awesome at the same time that I just didn't care. And at that point I had already kind of transitioned away from wanting to be in a band. I was way more into the production side of things, which I honestly had no idea I was going to like so much. I only got into it because there were so few people in the area that recorded that we felt could do it. Right. In fact, Josh was reminding me today, actually, one of our bands was we were going to play, were going to go record with Jamie King, the guy who did it all between the Bmy Records back then. Yeah. And so we

Speaker 1 (00:06:34):

In Carolina.

Speaker 2 (00:06:35):

Yeah, exactly. And so we were all saving up as a band and everybody in the band had to save up $700 and me and Josh were the only ones that actually saved up our portion. And so when no one else did that, it just kind of fell apart and we were just like, you know what? Let's just figure this out on our own. That's

Speaker 1 (00:06:51):

Really, really interesting to me that because I feel like that was the situation for me in lots of bands growing up where we decided something that I figured out we should do, and then I'd save up the money somehow, and I realized everyone had different means, but still I saved up the money other people, and I feel like I should have just dropped the projects right then and there because such a great sign of what's to come. Exactly. Because $700 seems like a lot to a kid, but it's not that much if you spread it out over time. I remember reading an interview with Maynard from Tool a long time ago, I think in 1998, where he was talking about advice that he gives people, and his advice was, sell your VCR, don't go to Starbucks, all the little things that you're spending $10 here, $30 there on. Just don't do those things anymore and put them into what your priority is and make your art your priority and you treat it the most important thing. It will become the most important thing. Absolutely. So

Speaker 3 (00:08:11):

True. Yeah, I mean back then it really was, we would just wake up every day, work on the songs all day, work on the recording, whatever cool edit pro or cake walk recording we were working on at the time, literally until we went to bed at five in the morning and wake up at 1:00 PM the next day and do the same thing again and eat fast food. But it's like that kind of drive I think that me and Joseph saw in each other is what carried over to when things started happening for Joseph producing bands and I was touring a lot. It made sense for us as I got more into recording as well to kind of team up and use our strengths together.

Speaker 1 (00:08:48):

How many years later though?

Speaker 3 (00:08:50):

Probably about three years, two to three years after that.

Speaker 2 (00:08:54):

Yeah, I think it was actually, I think when we had the original idea, it was when I came out to work with you guys on an album. I think it was The Powerless Rise,

Speaker 3 (00:09:03):

Right, right.

Speaker 2 (00:09:05):

I at that point had, I guess my thing, I don't know, had just been doing vocals really well. That was kind of my main focus, and me and Josh had that chemistry already, and so the rest of the band was cool if I came out and did all of Josh's clean vocals. So I came out and recorded all of that for the Powerless Rise, and it was kind of during that whole process that me and Josh had the idea maybe we should team up and do it for real.

Speaker 3 (00:09:29):

At that point, I had some means to buy some gear, and I think at that point I was 21 years old, 22 years old around that time, and so I was just like, I don't know, anxious to, I don't know, do something outside of just the band. We had so much off time around then six months a year that we weren't on the road. I wanted to be busy doing something, so doing something like a studio seemed like a great idea.

Speaker 1 (00:09:53):

It's interesting to me, I don't want to say really close friends, but I was in pretty constant contact back then with Nick especially, and Tim every now and again. And I just remember that there was a lot of recording talent in the band, but I never heard about you recording, so that was another reason for why it was really interesting to me that this is happening now. I had no idea that you were also doing the recording thing.

Speaker 3 (00:10:25):

Yeah, well, for me, like I said, it started out as more of a, I wanted an easy way to record stuff for myself, and Joseph had all this talent doing it and that he had kind of honed while I was out touring for the first few years I was in the band. And once we started working together, he kind of taught me the ways, and then especially around 2013 where we were forced to take a bit of a break, that's when I was able to really buckle down when we started doing woven war and I was doing a lot of the demos myself and Joseph had taught me how to autotune vocals and how to just track proficiently. And I think that around 2013 is where I really started making those connections and recording myself more often.

Speaker 1 (00:11:10):

I want to talk about that for a second because I think that it kind of circles back to the drive aspect you guys were talking about from the early days. I think that that 2013 era you guys had the force break. I think a lot of people might have gotten really depressed and stopped moving forward, but it kind of says a lot that you buckled down and really refined a new skill rather than get stopped in your tracks. And that it kind of goes back to that drive that I feel like you guys saw in each other that you guys had a goal, for instance, to record with Jamie King and only you guys came up with the money. And so that goal's out the window, and I feel like some people would've stopped right there, that goal, that dream would've been out the window and that's that onto the next thing. But obviously it was not the end for you guys and you kept going. And same with 2013, could have definitely gone down a negative path instead started this other career, which I think is super admirable, but just goes to show that drive that drive's got to be there no matter what's going on in your life.

Speaker 2 (00:12:29):

For sure. And I think it also helps, I think that's another thing that makes it so beneficial with me and him working together is that at that time, it was right when we had just moved, well, he's been out, he had been out in California, but I had just relocated from Alabama to la, which he convinced me to do. And 2013 was my first year here. And so after the force break, I mean I was here, we were just getting our studio started. I had just started working part-time with Atlantic Records, just doing writing sessions and all that kind of stuff. So we kind of had no choice but to just go full throttle into the studio at that point. And I think that we helped each other with that drive, like you were saying before,

Speaker 3 (00:13:14):

Before I really, I guess had the talent to man the helm myself. I was just really trying to tell people about Joseph and how talented he was and that he had tracked me on the Asle dying records and stuff like that. And it was definitely a slow build, but I think just the combination of having some extra time off and being able to be in a town where there was some things going, more things going on, I guess than Birmingham helped a lot. So yeah, man. And I also wanted to clarify to the listeners that our product, when we decided to record ourselves instead of going with Jamie King, definitely was not better than what we would've gotten had we recorded with Jamie King. I just had to point that out because I feel like we kind of phrased that as if we had an equal product the first

Speaker 1 (00:14:00):

Time. Oh, Jamie's great. We're good friends with him. So yeah, if he's listening, I hope you didn't take that the wrong way.

Speaker 3 (00:14:06):

And I also,

Speaker 1 (00:14:07):

We love you, Jamie.

Speaker 3 (00:14:08):

I hope he doesn't take it personally that we canceled a $3,500 project either.

Speaker 1 (00:14:14):

I think he got past it.

Speaker 3 (00:14:15):

I think so. Yeah, eventually pretty good for him. Eventually

Speaker 1 (00:14:19):

It would be rough if he didn't. So you moved to LA from Alabama, but you already had stuff going on,

Speaker 2 (00:14:28):

Obviously. Oh yeah. A lot.

Speaker 1 (00:14:30):

You had worked with Brian Hood, right?

Speaker 2 (00:14:32):

We were competitors.

Speaker 1 (00:14:34):

Competitors,

Speaker 2 (00:14:34):

Yeah. We were kind of the only, it sounds arrogant to say, but kind of the only real legit studios to record in Alabama

Speaker 3 (00:14:44):

For metal and stuff

Speaker 2 (00:14:45):

At that point for that genre. I don't want to put other people out, but yeah, I mean we were definitely competing against each other, and he actually started a good bit after I did. So there was the whole, and he kind of rose up a lot quicker than I did, so there was a lot of somewhat heated back and forth, that whole thing, but

Speaker 1 (00:15:05):

That's good though. It makes you better.

Speaker 2 (00:15:07):

I completely agree, and I think we both agreed.

Speaker 1 (00:15:10):

I think I actually had lunch with him a few weeks ago, and every time I see him I'm like, man, this dude is really

Speaker 2 (00:15:16):

Smart. Oh, he is. Absolutely.

Speaker 1 (00:15:18):

Every time I've been around him, that's always my impression. And there were times where I felt like he was a URM competitor and times where I've been like, no, I don't consider him a competitor. He does his own thing and it's always been like this back and forth, but I've always maintained that he is just one sharp motherfucker.

Speaker 3 (00:15:41):

Absolutely.

Speaker 1 (00:15:43):

Him existing makes me better. I feel like

Speaker 3 (00:15:47):

For sure.

Speaker 1 (00:15:48):

I know that he's going to come up with some really good idea.

Speaker 3 (00:15:51):

Oh yeah,

Speaker 2 (00:15:52):

Absolutely.

Speaker 3 (00:15:52):

Yeah. From my perspective, I kind of identify naturally more with the creative side, so hearing someone kind of kick my ass with some business knowledge on a podcast really helps me out. And I think Joseph out as well. We both listen to his podcast and it's definitely helpful.

Speaker 2 (00:16:07):

Totally agree. That's always been a thing for me. It's like I kind of get tunnel vision with the process, with the creative process and all of that so that I don't always think he does about the business side of things. So it's been very helpful to listen to that. It's motivating for sure.

Speaker 1 (00:16:22):

Again, like I said, I really think the dude has a great brain and he's taken, I feel like what he's done is he's taken some pretty sound or very sound practices that work. Some of them are kind of normal in the real world, but in our world, they're not normal at all. For sure. You need to learn them from someplace else. And so I find that musicians and producers who just learn this kind of stuff, whether they get it from him or from reading on their own, it, it's transformative because being able to actually run your stuff a serious business is the difference between losing your ass in hard times or thriving, I think.

Speaker 2 (00:17:15):

Exactly. You have to have both for sustainability.

Speaker 1 (00:17:18):

Yeah, absolutely. Okay, so you were doing a lot of work competing against him then you moved to la I've always thought that that's an interesting move. I've always wanted to, but I always kept on saying, I'm going to do it when I'm ready. I don't want to go to LA with nothing going on. And I realized it's already been 10 years where I qualified under my own criteria, but now I'm actively considering it. And that I read in the pre-interview notes really, really kind of struck me that I wanted to talk to you about. Okay, so Ben told me that you said that you never felt like LA was oversaturated. Maybe it was, but you never felt it. And I've always said that that oversaturation thing is a myth, and the reason that it's a myth is not because there aren't a lot of bodies, there are definitely a lot of bodies there, but because just like everywhere else, most of those bodies suck. And so if you really are great, as a matter of fact, you're going to stand out even more. I think

Speaker 2 (00:18:31):

It's so true,

Speaker 1 (00:18:31):

And you'll notice that even in LA there ends up being certain people who end up doing disproportionate amounts of work because they're that much better than everybody else. They try that much harder. They have that much more drive, they have that much more business sense, that much more skill. And so I've always maintained that you shouldn't worry about the saturation part, you should worry about A, how good are you? B, how good are you at networking?

Speaker 2 (00:19:01):

Absolutely. What do you think? Oh, it's so true. I mean, I had always been told before I came here that it was saturated. And I mean, like you said, everybody kind of says that about big cities, and so I certainly had formed that in my mind, but it helped a lot that I actually had a friend from Birmingham that had moved to LA to sign with Atlantic Records as a songwriter, and this guy named Michael Warren, he's incredibly talented, but at that time he kept being like, bro, you got to come out here, man. You got to come out here. I'm telling you you'd kill it out here. I'm like, I don't know, man. I mean, it's risky. And especially at that time, 2011, 2012 when I was considering it, I had gotten pretty comfortable in Alabama, and I mean, I certainly wasn't doing the caliber, no offense, but I wasn't at the level that I wanted to be in terms of clientele. I was doing more quality, I mean more quantity over quality. You know what I mean? I was recording like 40 bands a year, so

Speaker 1 (00:19:57):

That's a lot.

Speaker 2 (00:19:58):

Yeah. I mean, yeah, it was ridiculous.

Speaker 1 (00:20:00):

That's like a factory.

Speaker 2 (00:20:01):

It was the epitome of working hard and not smart, which it took me a little bit to learn, but he kept convincing me to move out. My friend Michael, and then once Josh was like, I think that's a great idea. I think we should really consider doing this. All it's going to take is this finding a spot. Let's just go for it. And he kind of pumped me up and we just put our heads together and we were like, we set a goal, we're like, we're going to move in one year. And so for that whole year we saved. I worked my ass off. We really got to the point where we were ready and everything just fell together. Josh found a spot. I got to

Speaker 3 (00:20:33):

Pop in here, and we even saved a ton of money on moving because we had an asle dying tour ending in Orlando, and the bus obviously had to deadhead all the way back to San Diego. So I set up this drop in Mobile, Alabama where we put all of Joseph's personal belongings and all of our studio gear from Alabama into the actual tour bus. There was chairs falling out of bunks,

Speaker 1 (00:20:56):

And man, I'm sure they loved that, or did everyone just fly?

Speaker 3 (00:20:59):

We all flew. So I mean, they were aware, but I don't think anyone except the bus driver was truly aware of how much additional weight was added to that bus. There was no

Speaker 1 (00:21:06):

Room. Well, hey, if they were flying, they didn't know it didn't happen.

Speaker 2 (00:21:12):

Exactly. We saved probably $3,000 at least of moving costs.

Speaker 1 (00:21:16):

That's interesting. About a month ago, I made the same goal. I said that I'm going to LA in a year. I actually think that that's the next step for URM.

Speaker 2 (00:21:28):

Yeah, nice. I would love that. That'd be sick.

Speaker 1 (00:21:30):

Yeah, it makes sense, right? It's one of those things where I'm very proud of everything we've done and more so that it's all been done remote, but I feel like if we had a headquarters in LA look out.

Speaker 3 (00:21:46):

Yeah. Well, one thing I was telling Joseph earlier is that I could totally understand if somebody is preaching, it doesn't matter where you're at, it doesn't matter if you're mixing something. You could be anywhere in the world. You could be on the beach and Bali mixing a record if you wanted to. That would be awesome. But there's something about being in a city like la, Nashville, New York City where the caliber of musicians and the energy that gravitate towards those places makes, even if you're kind of grinding at it like we did for a few years, just having that, I guess the cream of the crop kind of talent and those people, like you were mentioning the drive earlier, the people with the drive kind of go to those places since the industry's centered around them. So I guess it makes what we like to do a lot more fun when the artists are equally as driven. So true.

Speaker 1 (00:22:41):

And not just that there's an infrastructure there.

Speaker 3 (00:22:43):

Exactly.

Speaker 1 (00:22:44):

I feel like the music business is a super informal, unprofessional industry, but if there's any infrastructure to it at all, that's where it is.

Speaker 2 (00:22:58):

I mean, it's still pretty loose out here, but the people I work with don't really want to come in before noon, and you what I mean, which mean it suits me, but I'll have people call me trying to come into my studio at midnight, and it's just normal.

Speaker 1 (00:23:12):

I mean, music industry rules apply still, but at least there's an infrastructure out there and I feel like the amount of opportunity is just unparalleled. And I totally do agree that you could do things from any place else. I mean, I'm a perfect example of that. I have done things from any place else, but even that, I recognize that at some point, if you really want to get the maximum potential out of this, you won't really know what the ceiling is until you're around or in an environment where everybody is I guess thriving off of the same thing.

Speaker 2 (00:23:58):

Absolutely. And also I wanted to follow up on what we talked about earlier. I never really finished my statement about the whole it being flooded thing because really

Speaker 1 (00:24:07):

That's right.

Speaker 2 (00:24:08):

I feel like the key to that is I feel like I wouldn't recommend just anyone pack up and move to LA or you know what I mean, not just anyone. But what I found when I got out here, because like I said, it really helped because my friend Michael hooked me up with a job at Atlantic Records Studios, which was a great way to supplement not having any business instantly coming out to California for me and Josh's studio, we had to just start from scratch. So that helped tremendously. But what I found there when I started was that my work ethic and my ability spoke for itself. They didn't care that I had no school background, which I didn't do any of that. And the interns that were bringing me coffee and doing all this stuff had all just recently graduated from music school, which I mean, no dis to them, they're great dudes, but that just shows you, it's like, okay, they're here already.

(00:24:56):

They went through all the normal typical steps. I moved across the country and just instantly leapfrog all of the, you know what I'm saying? So it's just one of those things, if you are used to working your ass off wherever you are, if you are truly passionate about it, if you care more about what you do than the end result, that's literally all it. And I mean of course if you're talented, but when you, you're that prepared and you put yourself in the places to receive the right opportunity, you'll thrive for sure. And there's just been no, I don't want to say no competition, but really everybody else who just works together out here, the people that would be competition just want to work with me, not against me. That's what I found.

Speaker 1 (00:25:35):

That's because there is an industry with an infrastructure sort of out there where that's what I meant by everybody thrives from the same thing. It's not like there's two guys who do all the metal and

Speaker 4 (00:25:50):

Exactly,

Speaker 1 (00:25:52):

We're going to go neck and neck, the best man wins sort of situation. The city is built on entertainment and art. So I feel like there's this understanding between people that they are just an option of many options and it kind of forces, it does force a cooperation.

Speaker 3 (00:26:12):

Absolutely.

Speaker 1 (00:26:13):

And also I got to say that the leapfrogging thing, you can't forget the importance or understate the importance of having some connections to begin with because I think people need to understand that the whole networking thing, even though it's kind of a nasty word, it conjures images of NAM and bad business cards with perms and stuff like that. Really though I feel like it's the lifeblood and in lots of ways it's what will allow somebody to leapfrog.

Speaker 3 (00:26:51):

Absolutely.

Speaker 1 (00:26:52):

If you get there and you have a lot of drive and a lot of talent, but you don't know anybody, well, then you might not have the opportunity to show anybody that driver, that talent. And if you just know people, but you don't have the driver, the talent, then all of that might happen is you get one shot and then you never get another one. So you obviously have to have both. But if you do have that drive and you do have the work ethic plus you know people you will leapfrog. Absolutely.

Speaker 3 (00:27:22):

Yeah. And to that point, one of the cool things was the week we were moving out here, I just told the story about the tour bus as we were unloading the tour bus in San Diego to bring all the gear to la, we were given a live, it was like a live DVD shoot for the Mitch Lucker show for suicide silence when they had all the guest singers. And that was something that Daniel Castleman had passed on to us because he just didn't have the time to do it. For some reason, he was doing something else already, Daniel, right?

Speaker 1 (00:27:50):

Of course. I haven't talked to him in ages, but I have nothing but good things to say about him. These, he's great. They're a really awesome engineer.

Speaker 3 (00:27:58):

Oh yeah, he's worked on a lot of our stuff. So that was the first week we were here. We're like, oh my gosh, we're on top of the world. We already got this huge project instantly in LA and I had a lot of these, the networking contacts, but on the same, I guess at the same time, we didn't necessarily have any of those sort of blockbuster credits at that point. So that was where it became about the grinding, because my bands put out several records in the first few years that with woven war, at least when I was out here, and obviously we were test mixing for all of them and we didn't get it because there's a hesitation when you don't have that, I guess recognizable name quite yet. And so while the networking and being able to tell everybody I knew about the studio helped, it really just came down to just repetitively punishing and grinding

Speaker 1 (00:28:55):

And

Speaker 3 (00:28:55):

Just talking to everybody we could until you finally get that chance. And there's guys like Tommy Vet who we've had in here since probably the second month the studio was here and bad Wolfs is killing it now, and he still shouts us out. That's like the kind of relationships that we were able to build out here. And that kind of good experience with an artist is kind of its own networking because they tell their friends that are in bands that are doing real stuff. And I don't know, it's definitely complicated, but just so you know, even if you know a lot of people, there's still a pretty steep amount of grinding to be done.

Speaker 1 (00:29:34):

Absolutely. Well, I think that when you talk about a network of friends or contacts or colleagues, whatever, sometimes it comes off as if a mean something to the extent of have network will get gigs, and yeah, it's not exactly like that. It's more like if you check off all the boxes that you are friends with certain people who have opportunities around them and are doing the stuff you want to do, and they like you and they think you're good, a situation like the suicide silence show might happen for you because they are too busy and they feel comfortable passing it off to you, for instance. That's actually a perfect example. But that right there isn't going to guarantee what comes next because then you have to take that opportunity and knock it out of the park and keep going and keep going and keep going and make that same thing happen with hundreds of people that same, I know this person, I'm in good with them, they have good opinions of me and my work.

(00:30:50):

They feel comfortable giving me an opportunity and saying yes to giving me a shot. Basically. It kind of is that over and over and over again. And I think that at some point, your reputation exceeds your need to know everybody on a first name basis. For instance, if you do enough work, the momentum that it picks up will decrease the amount of networking you have to do. But really all that's happening is that somebody else is doing the networking for you, whether they're like Tommy Vex is shouting you out or somebody is finding one of your mixes on YouTube and being like, holy shit. It's either the music or another person is doing the work for you, but it's still getting out there and having that effect of changing somebody's mind. So I think at the beginning, it's especially important when you don't have the momentum that you have to create the momentum with relationships. And so if you have a few to begin with, it's more like kindling to a fire. I think that's more what it is than actually being the be all end all.

Speaker 2 (00:32:00):

Absolutely.

Speaker 3 (00:32:01):

Definitely.

Speaker 2 (00:32:01):

I think Josh, one of the things that I've enjoyed in partnering with Josh is he has been, I'm not really a social butterfly. I'm kind of a homebody, I'm workaholic. I like to, these are

Speaker 1 (00:32:14):

Most producers.

Speaker 2 (00:32:17):

Yeah, true. But I mean, Josh has facilitated so many of these relationships and these networking opportunities just from, I guess touring the world and playing with all these bands like Tommy Vex mean us doing Bad Wolves wouldn't have happened without that. So I mean, it is been hugely beneficial.

Speaker 1 (00:32:38):

Josh, I have a for you. So you said that you learned to record in order to do your own stuff? Yeah. Okay. Were you a vocalist first or did you learn how to sing for the same reason that you learned how to record to fulfill a need? Are you originally a singer or you got sick of singer sucking and decided to learn?

Speaker 3 (00:33:05):

Wow, it's kind of a combination of all that.

Speaker 1 (00:33:09):

There's a reason I'm asking.

Speaker 3 (00:33:11):

Okay, cool. Yeah. In Joseph and I's Band, for example, I was never, I think, intended, correct me if I'm wrong to sing anything on our first little EP that we did, but our singer at the time, I think he had blown out his voice while we were recording, and we thought it was possible to record six songs of vocals in two days before going on tour. And of course he couldn't do it, so I was like, oh, I'll hit a couple of these parts. And then it was like, oh man, this worked out all right enough with some digital help. And so I kind of from there started working on it a little bit more. But yeah, it was to fulfill a need. I was never at that point lead singer or anything. It was more of a backing kind of like the good cop, bad cop vocals that metal core bands have.

Speaker 2 (00:33:55):

He was good though. He's leaving that out.

Speaker 3 (00:33:56):

He

Speaker 2 (00:33:57):

Was a good singer at that point for sure. But anyways, continue.

Speaker 3 (00:33:59):

Yeah, I didn't take it seriously, I guess.

Speaker 1 (00:34:02):

And what was the second part of your question? Well, what I was wondering was, because if you had said, I always wanted to be a vocalist, then I'd would think, okay, cool, that whole social butterfly thing that Joseph was saying isn't natural to him, then I'd say, okay, well then I guess it's definitely natural for you if you're, because vocalists tend to be super extroverted, but would you consider yourself extroverted or introverted?

Speaker 3 (00:34:29):

I wouldn't consider myself the typical extrovert that's laughing the loudest or stopping the party to tell a joke or anything. But I definitely would fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum, I guess when compared with Joseph. I enjoy social occasions and networking, I guess if we'll use that word, but I definitely reach a threshold pretty quick, and I kind am one of those guys who does the old Irish goodbye and just kind of sneaks out the back without saying bye.

Speaker 1 (00:34:59):

I call it the,

Speaker 3 (00:35:00):

Yeah, exactly.

Speaker 1 (00:35:01):

Drop, dip, disappear,

Speaker 3 (00:35:03):

Dip. That's way better than Irish. Yeah, that is good. Yeah, I don't think I definitely actually always just imagined myself as a guitarist, actually what I played all the way up until the point where I started playing with the guys out here.

Speaker 1 (00:35:19):

Okay. Do you find that you've had to make yourself more social or in order to be able to do the networking thing, or it just kind of came naturally to you?

Speaker 3 (00:35:32):

Oh man. My personality, and I don't know if it was my upbringing or what, but I really like to listen to people and it really stresses me out when people interrupt each other. So when I'm listening to podcasts and everyone's interrupting each other, I have a visceral physical reaction to it. So I've always been more of a listener in conversations, but I found that sometimes you only have that one chance to introduce yourself, and if you are being, I guess, extremely polite and kind of dipping back in the corner for the conversation, you might miss that chance. So I think it's, for me, it was definitely a learning experience when going to things like playing these big festivals. We would play, when I first joined the band, there would be like Alison Chains was there and hell yeah was there, and Vinny, Paul, and all these people are there. And being able to, I guess walk up to a conversation that was not something that came natural to me. But with practice, I think anybody can kind of get better at just going, well, got nothing to lose. I'm just going to introduce myself.

Speaker 1 (00:36:37):

How did you train that? Lemme say one thing before you answer that. That's why I can't watch the news. All the interrupting, I can't handle it. I hate it so much. Just people talking over each other. One of the reasons that I actually prefer to do these podcasts in person, we're doing this one on Skype because we have to, but recently I've started doing them in person when I can, and Skype has this delay. It varies depending on the internet quality where people interrupt each other, not because they're meaning to interrupt each other, but just because the delay makes things weird is super unnerving. So I can relate to how frustrating it is on my end. It's just frustrating when it happens, even as a podcast host. But I'm asking you specifically because we deal with lots of people who are trying to become professional producers.

(00:37:36):

That's kind of the whole mission at URM, is to help people turn that dream into a reality. And the reality is that most producers are introverted. Like Joseph described himself, I'm the same way. I've had to teach myself to be social, but my natural self is super introverted, and I've found that the little bit that I have taught myself has gone a really long way. And I've seen a few people teach themselves how to do it and how to deal with it, and they've benefited tremendously. And so from somebody who went from a local band in Alabama to being in the room with Alison Chains, and how did you pick up those skills? How did you make it comfortable?

Speaker 3 (00:38:23):

Oh man. I won't say that it ever really got more comfortable, per se. It just became more, I guess, being put in more social situations and not just with larger than life bands like that, but just with my peers, I guess

Speaker 1 (00:38:38):

Tolerable, maybe the words tolerable.

Speaker 3 (00:38:40):

Yeah, it became more normal and more tolerable. And I think you just like anything, talking to a girl or a guy in high school, you kind of work up to it, I guess. And for me, it just was, I definitely would say if you talk to a band we toured with in 2007 when I first joined, they would probably be like, that's the quiet guy, the quiet weird guy from Alabama that doesn't quite fit in with these SoCal boys. But it's definitely, I think just being able to talk with more people improved that for sure.

Speaker 2 (00:39:14):

Yeah, I think it's practice, just like anything. I mean, for me, even it's gotten to the point where it's not really uncomfortable for me at all anymore. I mean, after having to work with so many people and go into all these situations now, it is kind of a thing where I would just prefer to be home, or I prefer to be in a smaller setting. I love talking to people. I love being social. Me and Josh can talk for hours with each other on end. You know what I mean? I am not a huge fan of going to big events with a million people and whatever, but having done it so much at this point, I don't feel even remotely uncomfortable. It's just not my number one option. So now it's kind of a thing where it'll be Josh like, oh, dude, we should go to the show. And I'm like, but I hate, I don't really care about any of those bands. And Josh is like, but

Speaker 3 (00:40:02):

Joe, what is your number one option? I'm just curious.

Speaker 2 (00:40:06):

Tell the listeners. I don't know, man. I mean, I'd honestly just rather be working, to be completely honest, either working or binging tv, something I don't know. But I'll end up going most of the time now. But it's always Josh yourself, do the one. Oh, yeah. I mean, it's super important. You have to do it just to show face.

Speaker 1 (00:40:26):

Yeah, I guess that whole thing about remaining top of mind, that's also why I want to move to LA is just for that top of mind factor. But I guess, sorry, I don't want to get redundant here, but to drive it home, I guess you're in the room with somebody that you might be somewhat starstruck by or who holds an opportunity that's really, really important to you, or who you really look up to or whatever it is. Or it's just a peer that you've seen online that you've wanted to meet but have never gotten the chance, not how do you approach them, but how did you get past that voice that stops you from approaching them, besides just doing it a lot? How do you break it's a, in the first place,

Speaker 3 (00:41:21):

A good, well, I can say from my experience, and this is something as recently as 2017, Joseph and I got the opportunity to work with Light the Torch, and it started out as just I going to do some pre-pro with Howard, Howard Jones, and I'd even toured with Howard, but when I toured with him, he kind of was a little more reclusive, so I didn't know him that well. And I guess the pressure of recording someone, even though it was just for demos and stuff with, I guess I, I'm so fond of as a performer, and just his voice is legendary. So working with him, I definitely felt some pressure still. But I think, I guess especially in the music world, or at least when working with bands that I guess hold that sort of prestige, I kind of view it as these people are here being vulnerable as well, and they're creating art, and that always comes from a vulnerable spot. So I think with artists, I guess it's always easier for me to level with them in that way, in the business sense. I think it's just, like I said before, it just became, I would say Joseph and I are probably some of the most anti, what would be the word?

(00:42:39):

I don't like to show up and just start talking about everything I've been doing at my studio. And I think sometimes in the past that's hurt us and we've become slowly more comfortable with posting something that's like, Hey, I co-wrote this song. Hey, I mixed this song. Because in the past you didn't want to come across as bragging on

Speaker 2 (00:42:56):

Yourself, bragging dish. I forgot what I did. Yeah, it's tough. It's tough to do for sure.

Speaker 1 (00:43:01):

There's a fine line.

Speaker 2 (00:43:02):

Yeah. Oh yeah, for sure. Oh, definitely. There's a fine line. But to back up what Josh was saying, I mean, for me, I think how I got over it or I got more comfortable with it was honestly just seeing the validation of what I was doing and how it was affecting the room. And honestly, working in Atlantic was pretty crazy in terms of getting over all of that. I mean, I was in the room with Florid and David gta and all this stuff, and obviously when it happened, at first I was like, oh, man, this is crazy. But once I got working, and once they were like, oh, man, you're good. And Floreta wanted me to at one point, wanted me to be his engineer full on.

Speaker 3 (00:43:40):

He wanted to move you to Miami, right?

Speaker 2 (00:43:42):

Yeah, it was an option. It would've so dope possibly. But yeah, so I was kind of like, okay, you know what I'm saying? I kind of got the confidence that, so I received that validation. So when those opportunities presented themselves, again, I was much more comfortable. I was like, okay, I'm ready. I got this. I mean, that certainly only applies to working with them, but I guess that's kind of the only times that I was really at that point, nervous about it anyway. It's like, can I keep up? Am I good enough to do what these guys need?

Speaker 1 (00:44:10):

It's interesting, that whole imposter syndrome idea of do I really belong here?

Speaker 2 (00:44:16):

Right.

Speaker 1 (00:44:17):

It's real. And I honestly feel like it never totally goes away, man. I don't know that many people who are very successful who don't have a little bit of imposter syndrome, unless their ego is just, I mean, we all know those ego monster types. So yeah, they exist the God's gift types. But I think nons psychopaths all have a little bit of imposter syndrome.

Speaker 3 (00:44:48):

I think it's that nagging kind of feeling of imposter syndrome that is what drives people to improve, or at least it was for me. It's like you reach that point where you feel comfortable with something, and that's the time without fail that I end up making a massive mistake because I got a little too arrogant or a little too cocky about the process or whatever. And I think that imposter syndrome is actually a positive tool as long as you don't let it overtake the ambition side of it.

Speaker 2 (00:45:18):

Yeah, I completely agree. I think for me, it was kind of an opposite problem where I never took time to really pay attention and acknowledge the things that I was getting to do because I completely agree with what you're saying. I feel like it's always the people who never feel good enough or never feel like what they're doing are good enough are the ones that rise higher. Totally. And it's always the guys who are like, I'm the best. That just suck. It just never fails. But at the same time, I do think that it's important to, and I've been told this by people, and I think it's good to sit back and look at what you've done and be like, okay, I'm on a good path. I'm on a good trajectory. You're seeing some success because that can push you further. But I do think that you have to never be satisfied. Always know that you have more to learn, always have room to grow and get way better.

Speaker 1 (00:46:09):

I feel like that whole sitting back and recognizing how well you've done is a 92nd thing. For sure. For sure. It's like keep it to 90 seconds and then move on. I've always had a really hard time doing it. People have told me that I should do it more, because sometimes I'll feel like no progress was made when a ton of progress was made. There's times where, for instance, I'll just feel like nothing has even happened in 10 years. I'm still in this tiny band and nothing's happened. I get this voice in my head, and that's just not reality. A lot's happened. So it's good to take 90 seconds to snap out of that and not just be like, yeah, rule, but just snap out of that negative voice. Because if you actually give into the negative voice, it'll keep you from moving forward as well. Exactly. I think it's

Speaker 2 (00:47:18):

Just be aware of it. Don't dwell on it. I think that's the thing. Just be aware of it, the success. So

Speaker 1 (00:47:23):

I think you brought up something really interesting about imposter syndrome. I've been talking to a lot of people who are coming to the URM summit, and one of the main reasons that people have said they're afraid to go is because of imposter syndrome. They're afraid that they don't belong in the room with a bunch of other producers. I guess there's a lot of producers there that are their idols, but they also have a feeling, an incorrect feeling that every single student who's bought a ticket is engineering for Colin Britain or something. And that's not the case. Not everybody is that advanced. There's all different levels of people and nobody's an imposter being there, but I feel like, so the imposter syndrome, if you have it, it's hard to get rid of. However you can use it for good or you can use it for bad. If it stops you from taking opportunities because you feel like you don't belong in the room, then that's a bad thing. But if it keeps you always sharpening the saw and always striving for more because you feel like you're not good enough yet not satisfied, then it's a good thing. So really, maybe it's just a matter of reframing, reframing it in a positive way because I feel like it never totally goes away.

Speaker 3 (00:48:46):

And I think the older I've gotten, the more I realize how much everyone is winging it. All the people that you look at and you think they have their shit together, they actually have it very little together. It's like everybody's still kind of dealing with the same kind of stuff you are. So I guess I've learned to appreciate that rush. I get when I'm doing something, I know I'm kind of out of my element in, for example, just the first songwriting gig that I ever had outside songwriting was with a bullet for my Valentine. And I had never once worked with an artist writing a song that wasn't my own song, but I kind of just acted like it was a normal thing, even though I was freaking out internally about it. But it ended up turning out to be really awesome. It took a couple of days to get firing off, but it was probably, that was the first time I was like, oh, I get it now. When people say that nobody really knows what they're doing. They're just kind of going with the flow. And I guess that's how the best opportunities had sort of happened for both Joseph and I, we you kind of get those opportunities to do something a little bit uncomfortable and obviously feel that imposter syndrome. I think it's a small amount of, it's healthy, but

Speaker 2 (00:50:00):

I feel like we end up doing better too when we're under the gun lifestyle. You have something to prove. It's a huge challenge. I mean, I think we're both pretty competitive by nature too, in terms of that, but getting those big opportunities, it is like a rush, like he said. But I also feel like I've done some of my best work in times like that where I'm like, man, this is pretty heavy.

Speaker 1 (00:50:18):

It's interesting because again, it's just what you do with it, I think, because there are some people who will take that uncomfortable, but good opportunity and crumble for some reason, other people who will, I don't know, it energizes them somehow. And I've done both, I guess. There's obviously been some things I've botched and some things I've totally won on, and I've tried to think about, well, what's the difference? What was I doing differently when I got that feeling that this is awesome, but it's kind of scary a little bit. It's a little much for what I feel like I'm capable of. And I realized that the times where I messed it all up, whatever it was, is because I was totally psyching myself out. I was focusing way too hard on what was wrong about everything, including me, rather than focusing really, really hard on how we're going to make this work.

Speaker 2 (00:51:23):

Yeah, totally. I think for me, it comes down to just how people view failure, because I think I've noticed a huge, some people love failure, some people hate, most people, I would say, are fear or they can't stand failure, so they don't want to take risks they don't want. That's all they can think about. And that completely prevents them from being able to operate at their maximum capacity. For me, I've honestly grown to love it because it's the only way you learn, really. It's the only way you can grow. So only you can get better is by messing up. And I think that you have to go into things going, I'm going to mess up. Okay. You know what I mean? Instead of thinking the whole time, oh no, what if I'm saying I feel like it's entirely about how you view that.

Speaker 1 (00:52:08):

Yeah. So it's almost as if we all are presented with very similar types of scenarios, and what makes all the difference is how we internally relate to those scenarios. So speaking of failure and those types of scenarios, were you always comfortable with it, or is that something you had to learn how to do?

Speaker 3 (00:52:34):

No, absolutely not.

Speaker 2 (00:52:35):

Absolutely not.

Speaker 3 (00:52:37):

I can relate this even to something not with recording or production or anything, was when I first started performing at these huge shows, I was kind of still in that zone where I was just riding the rush that I was talking about where I'm like, I don't really belong here, but this is fun and I'm just going to do what I can. But it's like when I really started to overthink things, it was like being given these DVDs of the board feed at a big festival in Europe, and you hear what you actually sound like, and then you go, oh, whoa, I was having a great time, but I sound terrible at this show. And the band's like, yeah, you sound terrible at the show. And then you let that kind of build up. And there was a couple of years where I really let it get to me, and I didn't even enjoy what I was doing because I was warming up just so long every day, and I was doing all these exercises.

(00:53:29):

I wasn't drinking at all. I wasn't eating spicy food. I had all these rituals. And it wasn't until I was doing, we were doing the powerless rise with Adam D, and he was like, you know what happened to me, man? I just started not caring at all because I've messed up so many times in the past. I can't mess it up anymore in the future any worse than I did already. And that sounds kind of counterintuitive or kind of like a cop out, but it actually worked so well. And since then, it's been easier for me to embrace the times that I fail because I think about the times that I failed worse before. So that sounds backward, but it actually, it works for me at least.

Speaker 2 (00:54:13):

Yeah. I think for me, I changed how I viewed what I was doing a few years back. I read the Steve Jobs biography. I know that's kind of random, but incredibly inspirational, like mind blowingly. So just the way that he, and he always preaches that too. He preaches that you should just embrace failure, because that's literally the only way that we grow and learn. You don't learn from your successes, you don't learn anything. So it's just through that. So I kind of started to view things that I'm doing as more of a product instead of something that I'm attaching myself to personally. So if people don't like what I'm doing, instead of me getting butt hurt about it, I go, why? What did I mess up? Oh, I didn't deliver here. And then I had a completely different awareness about the whole thing. I didn't take it personally. I feel like honestly, so many musicians and other people should incorporate this mentality to what they do, but they don't. But that has helped me tremendously. So whenever I'm doing something, it's more about what I'm doing. It's like a product. It's not attached to me personally. You know what I'm saying?

Speaker 1 (00:55:16):

Man, that's so hard of a point to get to though. I mean, it makes perfect rational sense, but it's almost like you have to learn how to quell this part of you that does not want to be okay with that sort of thing. And I think that with enough practice, it becomes very natural. And like you said, you can learn to embrace it, almost like the zen sort of thing. But I feel like it's a very unnatural thing, and especially for musicians, artists, producers, people who do creative work, there's this identity that we attach to what we do, which it's almost essential in some ways. So to be able to, I guess, infuse the work with that personality when you're doing it, and then disassociate yourself from it when you're getting the feedback that's like some mental gymnastics, some toughness, it's not very natural.

Speaker 3 (00:56:18):

Well, I'll say that Joseph and I differ in that a little bit because like I said earlier, I kind of lean more on the creative side of things. Usually my role comes a little more down to the creative decisions like production and tones and stuff like that. So I think there's a balance to strike where you don't want to be, I'll use Joseph's word, butt hurt by the critique, but I also feeling passionate enough to question that critique. You know what I mean? I feel like if I'm not passionate about something that I'm putting down onto tape or digital files, whatever you call it now, I dunno, there's a fine line to be struck to where you're open to critique, but also willing to defend why you got there in the first place. And I think that's where I try to improve all the time when working with artists or vice versa when I'm working with an artist and they get offended at my critique, is finding where that balance is and getting the most healthy version of it. Man, it's so tough. And Josh have had many

Speaker 2 (00:57:21):

Fights.

Speaker 1 (00:57:21):

Oh, sorry, go ahead.

Speaker 2 (00:57:22):

Yeah, no, I was just going to say follow up. Me and Josh have had many

Speaker 4 (00:57:25):

Fights. Stop interrupting.

Speaker 1 (00:57:25):

Sorry.

Speaker 2 (00:57:26):

I'm just kidding. No, I just completely agree with what he said and I think that's what makes me and him such a good team is because I do feel like there needs to be a healthy balance because I feel like there's always been a little bit of that in my personality. Josh always gets mad or upset at me before because I'll say something really hyperbolic about just judging an album or something that I think is bad because I have gotten so used to not attaching things to my identity that people could tell me something that I have sucks and I really wouldn't care. I'd be like, okay, that's fine. Maybe it does, but if I do that to someone else, people would get upset. They're like, Hey man, don't talk about my band like that. But especially when it's come to me and him working together, it's been a really useful blend because he certainly is still in that and I've kind of gotten a little bit more on the robotic side, so I think it's a really healthy blend to have both sides of that. He was just

Speaker 1 (00:58:22):

Saying, I feel like it's really tough with mixed notes. I feel like mixed notes are this thing that they're like the bane of so many mixers and producers existence, because on the one hand, some of those can make or break the record. Some of the notes are so essential and so good that if you don't pay attention to them, you might be missing out on some real genius coming in from the artist. And obviously there's other times where they're the dumbest idea you could ever imagine. They're going to just ruin all your work. It's like you work so

Speaker 3 (00:59:06):

Hard. True one db up.

Speaker 1 (00:59:07):

Yeah. Oh, it's so true. Or one PO. Yeah. Or completely pointless.

Speaker 2 (00:59:13):

Josh has gotten really good at breaking through my wall because I certainly get hardheaded about things, which I think that just goes with the territory. But yeah, Josh is really good about being Just try it. Yeah, just shut up. Just try it. And a lot of times I like that though. I kind of get excited when we're kind of getting heated a little bit because I think iron sharpens iron. That sounds erotic, but I mean, in the end, I'm very stoked. It'll be a battle and it'll be not fun in the moment, but in the end we'll come out with something so much better. You just said some of those notes are so essential, but then

Speaker 3 (00:59:47):

Well, you should bring up, how do you feel about Philo's Notes?

Speaker 2 (00:59:51):

Philo? I'm going to say it right now. The worst, the longest,

Speaker 3 (00:59:55):

Not worst. Not worse.

Speaker 2 (00:59:56):

Not worse. Okay. Some of them are just so relevant. It's literally what you just said. It doesn't change anything about the album for anyone other than him, which I understand that. I get it. And I don't fault him for feeling that way, but oh my God. So I, I've never worked with a band that had more notes. I'll just say

Speaker 3 (01:00:16):

That. But when you do get that one diamond in the rough note, that completely changes the vibe or completely just finally puts that finishing touch on the song.

Speaker 2 (01:00:24):

That's true.

Speaker 3 (01:00:25):

It's worth all those 0.1 DB

Speaker 2 (01:00:27):

L, and that's why you got to just go through it anyway. You just got to take it. And then when it's over, you're hopefully proud of what you've done.

Speaker 1 (01:00:34):

What's your policy towards notes? I know that there's some dudes who will say, I will do anything until you're happy. And I'm talking about it depends, top mixers who they have no limit on the amount of notes and then other ones who are like five revisions, that's it. Get your shit together, need them fast. And this is not a mark of success or failure because I know top mixers who are either way about it.

Speaker 2 (01:01:08):

Yeah, I mean for me, it really does depend on who I'm working with. I mean, I feel like if it's a big opportunity and if it's a band that you're getting to work with for the first time and you're really trying to establish a relationship with that band, I think you want to do whatever you can to make them happy.

Speaker 3 (01:01:25):

And you're probably less likely to really speak up with a forceful opinion in that situation, I would say, at least in my cases.

Speaker 2 (01:01:32):

Yeah, for sure. So I mean, I certainly have put limits on it. If it's an unsigned band sending me a project, I'm going to go, okay, you get three revisions. Anything after that you're going to have to pay, which I mean, what I find is mostly with those bands is they don't really have any notes Anyway. What's interesting recently I did upon a Burning Body album this year, they actually had zero notes, literally zero album notes, not one.

Speaker 1 (01:01:58):

Doesn't that scare you though?

Speaker 2 (01:02:01):

No, I mean, not in this case. I actually felt pretty confident about it. I was like, all right, is good. I felt like I was satisfied with that, so I actually wasn't scared. Sometimes I appreciate it though. A lot of times I'll send a first draft or a second draft and I'm like, okay, I know personally it's not there yet. I'm going to need a stew over this in my car. And you know what I'm saying, some mixes come real quick, some of them, it's a process. So in those, I actually do find notes to be incredibly valuable, but with that album in particular, I actually kind of agreed, which never really happens.

Speaker 3 (01:02:36):

I'm going to jump in here. I think the way you said that if it was an unsigned band, you would give them less opportunity for notes. Sounded kind of harsh as well. Well, I think what you meant though, right, is that you don't want to have one of those 50 bullet point notes per song with Pan this one to 71 to the left.

Speaker 2 (01:02:56):

Well, because happened.

Speaker 3 (01:02:57):

Yeah, exactly.

Speaker 2 (01:02:57):

As you know.

Speaker 3 (01:02:58):

I just wanted to explain that because I think it came off in a different way than you were.

Speaker 2 (01:03:01):

Right? Right. Sorry. Yeah, I guess I felt like that was kind of a given. I think everybody has to go through that at some point as a mixing engineer, but maybe not.

Speaker 1 (01:03:09):

Well, there's this thing that local bands don't have, which I think is experience where you will get guys in sign bands who have way too many notes, but they typically understand the limitations of a budget, at least for the most part. They understand when it's over, it's over kind of stuff, or we only have three days left, so we got to get it done. Those types of things are very real to people who have been on label deadlines and have labeled budgets. And I know that some bands get their budgets upped or whatever, but for the most part, if you've been dealing with labels and their budgets that they don't typically go up, and so you got to make some concessions. Even if you have long notes, you got to make some concessions eventually. And I feel like local bands just haven't experienced that. So not having experienced that can be way more unrealistic about their expectations.

Speaker 2 (01:04:18):

Yeah, I think I waited a pretty long amount of time to put a cap on that compared to others. I really want people to be happy. And so I would spend a lot, I used to just never give any limitations. I would just do as many notes as it took for them

Speaker 3 (01:04:35):

To be happy. But that's back when the mixes because of that and not really having any defined policy, it would cause these mixes to take six months because it's like, oh man, Ricky went on vacation. He can't get his vocal notes in until next week. And like, oh crap, we got to go. We forgot the harmony on the third chorus of whatever, and we're going to come in.

Speaker 2 (01:04:54):

Like I said, I was working harder, not smarter.

Speaker 1 (01:04:57):

So that's kind of what I meant too, that their notes can be detrimental. That can happen if you're not laying down the law. But I think also, especially at the very beginning, you really need to try hard to win bands over. So it's so hard to know where to draw the line because seen lots of producers that are showing some talent and first starting to get work, get really burned out in that first year of having momentum. It'll be maybe five years in to where they are finally making a living at it and their name is getting around, and so they're getting a lot more bookings and suddenly they're really busy and it's the first time that they've ever been really, really busy. So they don't totally know how to manage their time yet, and things can kind of spiral out of control because on the one hand, they're experiencing success.

(01:06:00):

They don't want it to stop and they want to make everybody happy so that they come back and the success continues. And finally, the tree is bearing fruit. However, on the other hand, if you let things go on too long like that, it's not good for anybody. And you'll end up pissing people off in the long run and records will get ruined and nothing will get done. So it's a really tough line to walk, and I've seen quite a few people get burned out because they feel like every single project just goes on forever. And at the end of the day, they're making half minimum wage.

Speaker 3 (01:06:42):

And I think we found, and this is something that I mean we're still getting better at to this day, is like you have to define the expectations to the artists upfront because I think when you don't do that, it becomes a burden on both sides. Because for example, if they don't know that they need to have their notes in by a certain day for you to be able to do those notes before your next project and they give them to you the next day after that, they were supposed to have it do, that means that they're actually not going to get their mixed notes for three weeks now or four weeks. And so it's like we found that early on we were making the mistake of not defining those boundaries and not defining those expectations, and the artists would complain at the end about it. And so that's something I would say one of the most important things that we've learned, especially since being out in la, is you kind of have to define those expectations of not only what they expect of you, but what you expect of them upfront. Because if you're trying to schedule out and run an actual business, you can't do it with, like you were saying earlier, earlier, the music industry kind of looseness,

Speaker 1 (01:07:47):

Man, I have made that mistake of getting the mixed notes in too late and then already being onto the next project. So not being able to get to them for four weeks, but not being clear about that in advance with the band. And so I would get mad at the band for not understanding that they didn't meet the deadline and therefore I have something else. And the whole time, I should have just explained it from the beginning, it's something I learned to do eventually when I realized that I was being an idiot by not, it was one of these things where I was right, so I felt like I was right. They should just meet the deadline. You don't meet the deadline. Shit happens. I got to move on with my life. I can't stop this next project that put down a down payment has their own deadlines. You didn't get the notes in, but at the same time, that's not the way you want to treat people that you want coming back. And so it all gets mitigated by just talking about it upfront and just being super, super clear.

Speaker 2 (01:08:56):

Totally agree. I mean, I think that you just have to, like he said, establish expectations and then exceed them. And I think I struggle with the same thing, like you said for a long time where I just felt like I'm right. You should see my logic. You should see my logic. You should deal with this.

Speaker 1 (01:09:13):

Yeah, because logical, right? My logic's logical see it,

Speaker 2 (01:09:16):

But the customer is always right. Policy still applies to some extent. So in the end, if you didn't, you know what I'm saying? If you didn't set someone's expectations, you kind of, that's your own fault and you have to deal with it. If you want to keep them as a customer, you kind of have to just do damage control at that point, which like you said, it'll sometimes projects get stacked and stacked and stacked and then you're just in way over your head and it's a mess. 18 hours a day. Yeah, I've done that. Oh my God. I mean, I've had bands walk in, I've had bands walk in while I'm still recording the previous band, and I'm just like, oh, this is just so embarrassing.

Speaker 1 (01:09:51):

How did that happen? Did you just overbook yourself or just didn't get done? Yeah,

Speaker 2 (01:09:58):

Absolutely. Overbooked myself, which was a problem. What year was this? 2011? 2000? No, 2010 I think. Yeah, it really ramped up back home in Alabama, and I was doing so much work was just, I mean this one particular week, I worked like 130 hours, I think in one week. I stayed up all night, three days in a row trying to finish this band. Oh yeah, not, wow. Wasn't nice then. And I still didn't finish, and a previous band just walks in and I forgot that it was going to be that night instead of the next day. And I just had to be like, guys, I'm so sorry, but can we postpone? They were so angry, but it ended up being okay. But yeah, those mistakes cannot keep happening if you want to have run a sustainable business,

Speaker 1 (01:10:44):

Obviously. That's exactly what I was talking about though, about that trap that producers get at the beginning of their success, that overbooking trap.

Speaker 2 (01:10:56):

It's hard to avoid because you need the money too, so it's really easy to get caught up in it.

Speaker 1 (01:11:01):

Well, you've been working so hard for so many years to get people to say yes to you, and they're finally saying yes to you, so now you're supposed to say no.

Speaker 4 (01:11:10):

Exactly.

Speaker 1 (01:11:11):

It doesn't make any sense. It's really, really tough. How did you fix that? How did you stop doing it? What steps did you take

Speaker 3 (01:11:23):

Using an actual calendar on your iPhone? Crazy little things

Speaker 2 (01:11:26):

Like that. Who thought that kind of stuff. I just grew up. I made, that's the thing, I made the mistakes enough times to learn from them. That's why I keep saying I was just failing and I wasn't an idiot, so I paid attention to what I was doing. And a lot of times it was even having Josh working with me, being like, dude, you can't do that, man. You know what I mean? I'm like, well, easy for you to say, dude, you're not, you know what I mean? So it was a thing, but he was just right in the end, and I knew that. And so I also had a problem back then with I would sleep in sometimes. I don't know, just dumb stuff like that you cannot do, you can't afford to do, and I feel like

Speaker 1 (01:12:09):

I did that too.

Speaker 2 (01:12:10):

If you make, yeah, I've heard of other people doing it too. It is the worst feeling in the world, but if you do it and you learn and you realize how awful that was you, that traumatic experience, hopefully you won't do it again or too many more times. Well, you know how from those mistakes

Speaker 1 (01:12:28):

Stopped doing it was I stopped letting projects go super late because the times, so I've had lifelong insomnia that I recently got. I wouldn't say it's, wouldn't say it's a hundred percent fixed, but let's just say it's 85% fixed. I can kind of relate 85%. I mean, last night I couldn't fall asleep till 7:00 AM but that happens. But that only happens three times a month now as opposed to every day of the month. And when I was recording for a living and I didn't set boundaries on projects, I would let them go till one in the morning, two in the morning, three in the morning, then the session's over and I'm fucking wired. Insomnia is in full gear. I'm not one of those people who could just go to sleep. I'm sure you know those types.

Speaker 2 (01:13:26):

I am that type.

Speaker 1 (01:13:27):

Okay, so yeah, I hate you, but

Speaker 2 (01:13:31):

I go to bed at 5:00 AM almost every night, so I feel you there.

Speaker 1 (01:13:34):

That is so amazing. Yeah, so I'm not one of those types. And so after the band would leave or the session would be over, then I need three hours to unwind the hamster,

Speaker 2 (01:13:49):

Decompress,

Speaker 1 (01:13:49):

Get the hamster wheel to shut down. By that time it's six in the morning, so getting to sleep at six in the morning and then what we're going to start working at 11. There's only so long that you can do that before you end up sleeping in

Speaker 3 (01:14:05):

And you're not going to be on the top of your game either when you're always on lack of sleep, and you take it as this badge of honor of like, oh, I pulled an all nighter. I'm getting so much work done, but there's no chance that work is as good as if you were getting seven or eight hours of sleep and just being on a normal schedule.

Speaker 2 (01:14:22):

Absolutely.

Speaker 1 (01:14:23):

When did you stop doing the all-nighters?

Speaker 2 (01:14:27):

I think when I got too old to be able to pull it off. I mean, I'm still very much a night owl. I mean, I'm not the kind of guy who just falls asleep ever. I do not fall asleep. I actually have to make a conscious effort to lay down and have a wind down routine.

Speaker 1 (01:14:44):