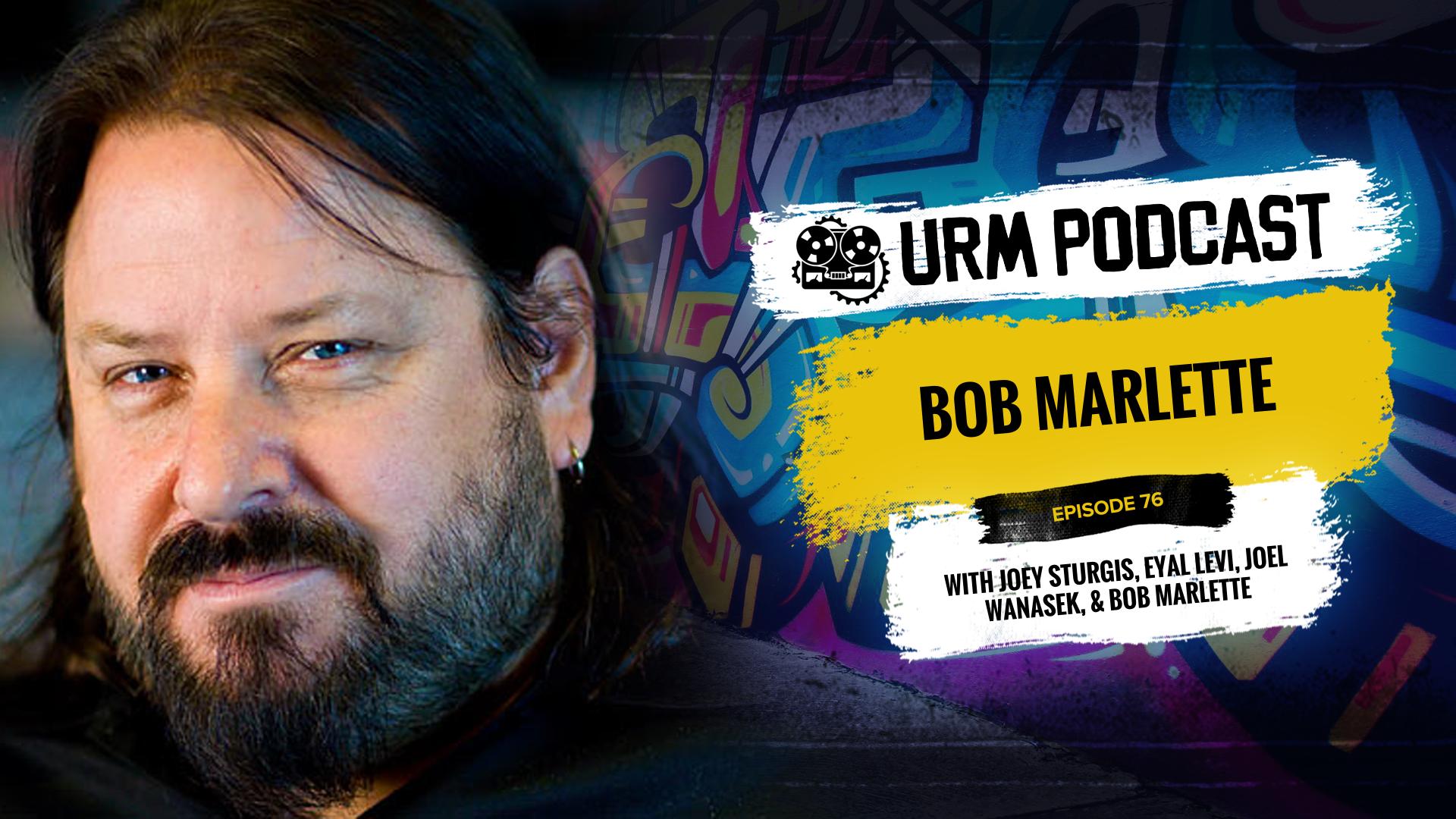

BOB MARLETTE: Working with Rob Zombie, The Producer’s Real Job, and Songwriting Before Gear

urmadmin

Bob Marlette is a producer, songwriter, and musician whose career spans five decades and a wide range of genres. He’s known for his work with rock and metal heavyweights like Black Sabbath, Rob Zombie, Rob Halford, Alice Cooper, and Shinedown. His diverse discography also includes credits with artists such as Tracy Chapman, Cheryl Crow, and David Lee Roth, showcasing his ability to adapt and find the core of the music regardless of style. A multi-instrumentalist who started as a keyboard player, Marlette was an early adopter of music technology and has also scored films for Rob Zombie.

In This Episode

Producer Bob Marlette sits down to share some serious wisdom from his five-decade career. He gets real about the challenges of film scoring versus producing bands, using his experience with Rob Zombie as an example of how a director’s vision shapes the process. Bob explains his core philosophy: a producer’s main job is to be an advocate for the audience, ensuring the artist’s message connects. He discusses how he stays on the cutting edge, evolving from early synth tech like the Fairlight CMI to a modern Pro Tools workflow, and how to identify “pivotal” new gear that actually matters. Most importantly, he hammers home that a great song and a passionate performance will always trump any piece of gear or production trick. This is a masterclass in mindset, longevity, and focusing on what truly makes a record timeless.

Products Mentioned

- Avid Pro Tools

- Apple Logic Pro

- Steinberg Nuendo

- Dangerous Music

- Universal Audio 1176

- Empirical Labs Distressor

- UAD Plugins

- Waves Plugins

- Flying Faders (Automation)

- Fairlight CMI

Timestamps

- [02:27] The surreal moment of hearing your own song in a movie theater

- [07:35] The unique challenges of film scoring versus producing bands

- [08:50] How temp tracks from other films can limit a composer’s creativity

- [13:57] Why artists with a clear, good vision (like Rob Zombie) are so rare

- [17:10] The producer’s main job: Being an advocate for the audience

- [22:49] How radio marketing demographics created musical “boxes” for listeners

- [25:01] Why long album cycles can hurt a band’s connection with their audience

- [27:54] An awesome story about meeting Paul McCartney at Henson Studios

- [32:52] How Bob stays on the cutting edge of technology and music

- [35:05] Identifying “pivotal” new gear versus short-lived fads

- [39:24] Working with one of the first Fairlight CMI samplers in the US

- [45:24] Does working on a computer boost or limit creativity?

- [50:17] Dealing with modern musicians who aren’t as skilled as players from past eras

- [56:06] Bob’s “secret sauce” for success: Relentless energy and great songs

- [57:36] “What’s the cure for a shitty snare drum sound? A hit song.”

- [01:00:28] Getting a killer drum sound by recording in his dining room

- [01:05:07] Why he’d rather have his teeth pulled than record to analog tape now

- [01:07:21] The importance of adapting to new technology to stay relevant

- [01:10:49] Bob’s number one piece of advice for aspiring producers: Say “yes” to everything

Transcript

Speaker 1 (00:00:01):

Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast, brought to you by Focal Audio, the world's reference speaker. For over 30 years, focal has been designing and manufacturing loud speakers for the home speaker, drivers for cars, studio monitors, for recording studios and premium quality headphones, visit focal.com for more information. And now your hosts, Joey Sturgis, Joel Wanasek and Eyal Levi.

Speaker 2 (00:00:30):

Hey everyone, I'm back. I've been gone for a little bit. Okay. Welcome back, Joey. Thank you.

Speaker 3 (00:00:36):

We are having so much fun Without you, you had to just come back and ruin it.

Speaker 4 (00:00:40):

I know, I know.

Speaker 3 (00:00:41):

I'm kidding. But I don't know.

Speaker 4 (00:00:44):

It is interesting having you back though. Welcome back. We did four episodes without you.

Speaker 2 (00:00:48):

Well, I appreciate you guys carrying the torch while I'm gone. And for those of you listening, if you're not well aware, this is the Unstoppable Recording Machine podcast and we are talking to someone who is legendary in the music scene and we're very grateful to have him on the show, very thankful for his time. His name is Bob Marlette. Welcome to the show. Bob. How are you doing? Thank

Speaker 5 (00:01:10):

You very much. And by the way, just so we're clear, legendary just really means old, really good. It just means you've been doing it long enough that they got to put a new term on. Oh yeah, he's legendary.

Speaker 4 (00:01:24):

I'm going to read some of these credits off for people who don't know and then we can argue about the legendary Bart, Rob Halford, John five, David Lee Roth, black Sabbath, quiet Riot, Rob Zombie, Atreus Saliva, shine Down Seear and more. I could just keep on listing them, but those of you listening to get the idea, Bob's worked on a lot of awesome shit. So once again, thank you for being here.

Speaker 5 (00:01:49):

My pleasure. My pleasure, gentlemen. It is funny because it is like when I hear the list, it's like somebody will come up to me and it's like, oh man, you did that record in 1982. I love what it's like. Hell, I can't even remember yesterday. You want me to remember serious details from a record I did in like 79 or 80? It's pretty funny.

Speaker 4 (00:02:18):

Do you ever hear stuff that you worked on and it sounds familiar, but you can't quite place it, and then you realize that, oh

Speaker 5 (00:02:24):

Yeah, you

Speaker 4 (00:02:25):

Realize you worked on it, you produced it. Oh

Speaker 5 (00:02:27):

Yeah. That actually, that happened in the movie theater. We're watching the Talladega Nights and we're watching this movie. I

Speaker 3 (00:02:37):

Watched that this weekend. That's crazy.

Speaker 5 (00:02:40):

I went to the, because my wife and son and the three of us were in the theater and watching and it gets to the big finale race scene and it's just rocking and all that. And my son nudges me and go, dad, listen. And I go, huh. And he goes, dad, listen to the song. And I went, oh shit, I did that. I love moments like that, like wow, it's cool because more times than not, as you guys know, when we have objective listening, we're listening with our little analyzing brain hat as opposed to, wow, that just makes me feel good. And that's one of the things that's tough to maintain when we do this for a living is the listening for pleasure versus listening for, oh yeah, I hear the wheels turning on that. They use this compressor or they use that EQ or, so it's nice to have that sort of listening, just a purely fun and objective.

Speaker 4 (00:03:51):

How often do you actually listen just for fun?

Speaker 5 (00:03:54):

Almost never. I know after that whole beautiful thing, it is like, eh, not really.

Speaker 4 (00:04:04):

It's hard to do.

Speaker 5 (00:04:05):

It is. It is hard to do because part of it is listening to things where you're not using it as a reference point. Because most of what we listen to, we're listening with a reference point. We're listening, we're being our track or our mix or whatever against another song. And we're always listening like that. And it's like there's one of the few bands that I actually listened to for Pure Pleasure is a Scottish band called the Blue Nile, and I just love the hell out of this band. It's a band that their first record, I think they made in 1981 or 82, but this beautiful, you just hear the Scottish mirrors and it's so beautiful and it's like, I love that record. There's not really a lot about it that you listen and you go, oh, they did this or did that. Because it sort of predates a lot of things and I love that record. Sorry, I go on and on now and again, so you just slap me if I lose focus. So yeah, thank you.

Speaker 4 (00:05:16):

I feel that way about movies too though. When you're watching a movie, you shouldn't realize that you're watching a movie. You should just be in it When you're listening to music, hopefully you can try to not listen to the production and just listen to the music, but it's hard to do.

Speaker 5 (00:05:35):

Yeah, it's the idea to transcend all the other stuff. And it is funny because that's actually my real relaxation at this point in my life is actually film and tv. The thing that it allows me to sort of transport my brain out of my universe into another one. I think that's what I love. And this last year I was actually trying my hand at scoring. I scored the new Rob Zombie film and had a lot of fun doing that too.

Speaker 2 (00:06:09):

I'm looking forward to watching that. Same here.

Speaker 5 (00:06:12):

But as always though, it's the truth is it doesn't matter what you do, the grass is not greener. It's like

Speaker 2 (00:06:21):

That's a good point. That's something that I think we spend a good amount of time trying to express. At least I do. It's like it, once you get into the big leagues, things only get harder and the stakes are higher and things are more complex, which is fine. It's just,

Speaker 5 (00:06:40):

You're right. I mean, as we were talking about earlier how it doesn't matter what you do and how many years of experience or success you have doing this, there's always somebody that is going, do you think this snare should be a little brighter? There's, that's the nature of it and it doesn't matter. And I really sort of saw that because I had this sort of, I guess esoteric view of film and music and film that I was going to sort of transcend earthly handcuffs, the barriers into this wonderful abstract film. But then you realize it's exactly the same deal you're having to fit this into that make it work so an audience relates to it. So essentially it's all the same parameters apply. So

Speaker 4 (00:07:35):

Yeah, while we're on the topic of film scoring though, I know that lots of our listeners, maybe they don't get into actually making film scores, but a lot of 'em are very attracted to film scoring, to composers and to that whole world. It's the kind of thing that a lot of people say they want to do one day. What are some of the challenges? There's got to be some unique challenges to that. What are some of the things that someone who maybe has only been producing bands wouldn't expect is challenging about scoring a film?

Speaker 5 (00:08:08):

Well, first of all, I think I went into it because remember, I started out actually as a keyboard player. That was my, I know a lot of people think I was a guitar player or bass player. I play so much guitar and bass on records, but I was technically, I was a keyboard player. That's what I came up as. So I went into it with this really sort of glassy-eyed, altruistic sort of like, oh my God, this is so great. I get to look at film and then find the emotional relationship and then translate that into musical color. And I had all these wonderful ideas of what it was going to be. And then the reality set in is a contemporary scoring for film for the most part is a director and a music supervisor taking cues from other films and putting him in a temp and sort of saying, yeah, that's what we want. And then sending you that chunk of music with already pre-designed emotional content and bumps. And so it was a lot more sort of physical labor of saying, I got to make this bump land exactly at frame number, whatever, and a lot of things like that. So I was surprised to a certain extent, I was hoping for a lot more sort of esoteric, beautiful experiences than I got a lot more technical like, oh yeah, we need to make this happen.

Speaker 2 (00:09:52):

I heard when Trent Resner was scoring the social network, he was making tracks that weren't necessarily timed to the video. He was just kind of exploring sound. And once he reached a certain point, the director started cutting scenes directly to some of the audio stuff that he was doing. So the audio was actually starting to lead the movie a little bit. I don't know if that's something you've experienced

Speaker 5 (00:10:19):

Actually, that had happened to me years ago when I had written a song for a film about last night, the original one with Rob Lowe and Demi Moore, and I had written a song in that, and Ed Zwick was the director on that. And that was in a case where I had written this song and then he was like, oh, the film, we played that track outside in the rain when we were filming it to get the emotion, and then he cut it to that same kind of deal. Again, though I think it really is more about as always, a creative flow. In the case of trance work, I could see how they would do that because I think the director in that could be influenced by a track and a mood that sort of created, in this instance, this was more of, I don't know if you've seen any of Rob Zombie's films, but from my understanding, he really does.

(00:11:22):

That guy, after having done a record with him, that guy's really clever. He knows what he wants, he knows how he wants it to be, and it's pretty specific. And as you were saying, my dream was to be that I could sit down and create this beautiful Shaw shank esque, beautiful textural layer of things and then let it sort of develop and morph. But in this instance, it was a lot more specific about fitting into exactly what Rob had wanted. But again, though, ultimately my dream is to do a film that's a little bit more like what you were describing with Trent, do

Speaker 4 (00:12:07):

You think it's affected by the fact that Rob's a musician too?

Speaker 5 (00:12:11):

Absolutely. Absolutely. I think that's very much so, because again, I really respect him because he is a guy who sees the big picture, and it was pretty interesting making that record with him. There was such a, for me, it was really unexpected. I went into it thinking how it was going to be this kind of heavy sort of thing. And then day one, because John five and I had written probably 20 ideas that we demoed here in LA and we get in day one and Rob's like, well, don't really like anything I've heard so far to see. John's face was brilliant. I mean, he just was like, what? And to me, I was like, okay, well, this is interesting. And then the first thing he played us is this really sort of eclectic captain beefheart slash weird Tom waits track, and he was like, yeah, this is cool. And I'm like, holy shit, that is cool. And then he said, let's do something like this. And I'm like, okay, cool. Game on. And that's why it was so much fun doing that record. It was like there literally wasn't any pre-designed concept on any, but it was just literally walking in and him throwing an idea out, and then we built a record on that. It was so much fun. We had a blast.

Speaker 4 (00:13:48):

So is that normal when you make records for the artists to come in with that much of a vision, that's actually a good vision?

Speaker 5 (00:13:57):

No, it's incredibly rare, and it's wonderful from my standpoint because then that is a record that's driven by an artist, and there's nothing better than a record that is truly driven by a strong artist who has a vision and has an ability to see a big picture of what they want. Sadly, it usually isn't like that, sadly. It's more of a case of when the band walks in and it's like somebody says, man, I love what you did on this record, man, can you make it sound just like that? And that's when it gets kind of sad sometimes. Then it's just like, dude, it's like that's why I fight for each record to try to have as much of its own identity. That's one of the reasons why when you really see my body of work, you'll see it'll go from Leonard Skinner to Rob Zombie, from Alice Cooper to Cheryl Crow, Tracy Chapman, a Black Sabbath. It's like, that's what I love most about doing what I do, is that I really liked it every time out, change it up as much as I can. The problem is when you have a certain measure of success, there's people that say, okay, well let's get Bob to do this because he did the last three bands that were huge doing this thing, and then there's an expectation of you delivering that same thing. So

Speaker 3 (00:15:34):

How do you reinvent yourself in that situation? Because I mean, I've always been a very branding focused producer. So an artist will come in and I'm like, all right, guys, what can we do that's different, but that's in line and et cetera? I'd really focused a lot of my energies on making bands interesting and having a unique selling proposition. So how do you go in when a label comes to you or an a and r guy and says, okay, I love the last three records you've done. I want you to make one just like it, and you're sitting there, well, this band isn't that, but I've got deliver. How have you always handled that, right?

Speaker 5 (00:16:05):

Well, number one, the good news is, like I said, I started out as a keyboard player, but I was also a songwriter from day one. So if you look and you'll see how many songs I've written over the years, and the one thing that I have learned about years of doing this is that an a and r guy doesn't necessarily want it to truly be in the box. He just wants it to be fucking great. So to him, he just wants success and he wants great, and if it can be at least somewhat original, they're happy with that, so long as it's good, and it fits fundamentally the genre that the band is and makes it work. So I think there's more wiggle room than we think doing what we do. And I'm a guy that likes to wiggle. It's like I really enjoy challenge it.

(00:17:10):

You have to understand my job is twofold or actually threefold, essentially, because my job essentially is to be an advocate for the audience. My job is to get the audience to understand what it is that's going on, helping the band articulate to the audience what it is they want to do. But the other ingredient in my career is that I got to love doing it. I got to have fun, or I'm just going to go sit and watch tv. I'd rather sit and watch TV than do something that's boring and stupid and not interesting. So that's why I make sure I challenge myself first, and then I challenge the band, and then I make sure that between myself and the band, we are relating to the audience in a way that they can assimilate the information in the right way that connects. People will ask me, well, how is it that you could go from Laura Brannigan, Rick Springfield, Tracy Chapman, Cheryl Crow to Rob Zombie, Marilyn Manson and Shine Down, and all those kinds of bands. And it's very simple. It's exactly the same. It's all the same. It's music. It's just figuring out the language that you need to speak so your audience relates to it. And so if I'm working with Tracy Chapman, it's making sure that that visceral connection is there, that the audience can go, oh my God, listen to I got a fast car. They go, oh, and if it's black, that it just feels mega and huge and just crushing. So it is just figuring out what it is, what is it, and then connect it to the audience.

Speaker 4 (00:19:15):

So do you have a technical way to figure out what it is, or do you have a routine prep work that you do, or does it just come to you like a light bulb turns on?

Speaker 5 (00:19:27):

I'm pretty lucky. It just kind of boom, boom. Yeah. Like I said, whether you want to call it luck or just a discipline of years and years of doing it, even when I was a kid, I was the guy who always was home practicing, and I just loved music so much. I just listened to everything. And I grew up in a very interesting eclectic household and just we honored creativity and ideas, and that was sort of the beginning of the nurturing of everything. My parents were just spectacular about pushing creativity and individual thought. And back in the sixties and seventies in Nebraska, that was a rare, rare thing. So trust me, I am a blessed, blessed man, but yes, for the most part, I don't have, it's not this huge process. It's more like, oh, I know what this ought to be. It's like, and boom, there it is.

Speaker 4 (00:20:36):

I think. Sounds like the huge process was all the years that you spent getting music into your DNA.

Speaker 5 (00:20:44):

Oh, absolutely. A hundred percent. And the cool thing about growing up in the time period that I did was when I was a kid, it was sort of the beginning of FM radio. So when you listen to the radio, the playlist was so eclectic. The playlist could be Frank Sinatra, led Zeppelin, Crosby, stills, Nash Young. It could be then go immediately to anything. So when you listened, you didn't categorize in your head what music was. Nowadays, when you're listening to generally to a specific serious channel, or you're making your selections on Spotify or Pandora, whatever, you're listening to things that tend to be inside the box that you sort of put yourself in. So whereas I never made, there wasn't ever really, oh, I only listen to this. It was quite the opposite. It was try to be as wide and as open as possible. That's why as a kid, I went from to Coltrane to ZZ Top to Miles Davis. I mean, it was such an eclectic sort of way of looking at it. And so that's why to me, music isn't a singularity. It's just this sort of wide, it's all music, it's all the same.

Speaker 4 (00:22:27):

Do you find that, I guess with the way that radio has evolved into things like Spotify, I mean, I know that radio still exists, but the evolution of how people consume music has kind of taken it to where you get everything on demand. Do you think that that's kind of killed people's versatility a little bit?

Speaker 5 (00:22:49):

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. Because there was a guy, and I always forget his name, there was a guy in the eighties that came in and he was one of the first guys to figure out what if we only play this kind of music on this radio station, then we can appeal to this advertising demographic or advertising group that really needs to target this demographic. And that was the beginning of us being in a box, because all of a sudden, the radio station would only play this kind of music or this kind of music depending on who they were going for for their advertising dollars because they needed to clarify to an advertiser, Hey, this is who our audience is, and if you want to reach that demographic, here's where it's at. And that really put the box around younger kids because they started, how remember those corn shirts, the band corn?

(00:23:59):

You remember how big a deal that was? Like you saw that kid with the corn shirt, and it's like he was saying to everybody, this is me. I'm badass, I'm cool. I'm wearing a corn shirt. But that was just essentially the tip of the iceberg because then it's like that guy would only listen to that kind of thing with his friends. And when I was a kid, you loved Led Zeppelin, but you also listened to everything else. It's like part of it was the Beatles really did set us on the course for showing us how to do it the right way. Okay. People forget Beatles were a boy band. She loves you. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I want to hold your hand, but how quick did they go from that to Sergeant Pepper? So three, show three.

(00:25:01):

Yeah, exactly. Well, one of the other problems, and again, I may be going on here, but this is another thing that is a pet peeve too, is nowadays you make a record, you push the hell out of it, and you work that record for three or four years. Well, Beatles made how many records in between that first one. And Sergeant, I always said that was what I felt one of the problems with one of the artists I worked with a while back, Amy Lee from Evanescence, and I said that was one of the problems that they had was there was probably four years between the first and second record. Well, what happens to that demographic in that four year period? They go from being a 15-year-old girl who is sitting in her bedroom listening to Amy Lee to a college kid, and what happens when you go to college, everything changes. As opposed to saying, you make that record when she's 15, then you make another record that grows a little bit and it grows and it keeps growing. So you're evolving with the audience. And that's what the Beatles were so brilliant at

Speaker 4 (00:26:26):

Their whole career was what, seven years? Yeah.

Speaker 5 (00:26:29):

It's

Speaker 4 (00:26:29):

Insane,

Speaker 5 (00:26:30):

Staggering what they did and the music that they made, and it was just like, that is absolutely breathtaking what they did.

Speaker 4 (00:26:39):

Yeah, I mean, they were together longer than seven years, but from the time that they broke, I believe all those albums elapsed time, seven years, something like that, it's kind of insane.

Speaker 3 (00:26:49):

That really puts it into perspective, you know what I mean? Just think about the average album lifecycle now and how much weight a band puts into an album, and then several years go by and you're like, what are you guys doing? Oh, we're working on a new album still.

Speaker 5 (00:27:03):

Yeah. Well, I mean, part of the problem is remember an album back in the day was, I mean, I saw a real interesting McCartney blurb thing, and he was talking about this is that they'd write a song and then they'd go in the afternoon and George Martin would be, what do you got for us? It's like he'd go, Hey, I got this little thing. What do you think? It's like, great, let's do it. It was a finished record within two hours. That was it. It was done. So it's not like today where it's like the band comes in and six months later we have the record. It's literally that moment. It was that moment. It's like, let's do it.

Speaker 2 (00:27:53):

I think they had the right idea.

Speaker 5 (00:27:54):

Absolutely. In more of, I tell you, I got one of the, for me, one of my most amazing moments and experiences with, I was producing Alice Cooper at Henson Studios and McCartney was in the room next to us, and I was working on something. I was in the room and McCartney comes over to say hi to Alice, and Alice wasn't there, and I was just sat with McCartney for about half hour or so just chatting, and I was like, oh my God. Well, let me rephrase. The first thing I had to do was remember to breathe because the second, yeah, I'm so jealous. The second that he walked in the room, I was like, I mean, what he meant not just to me, but to society and life in general, what he had. And I just was like, holy Nikes. And he was the coolest beyond cool, great guy, funny, and it was just so spectacular. But for me it was that opportunity to go, Hey, did you really, it's like all of those things that you thought about and never got to know until that moment,

Speaker 4 (00:29:19):

And did he actually answer?

Speaker 5 (00:29:21):

Yes, he did. And he was very, very cool and very forthcoming with just about everything. I mean, it was just a very cool, but let me just say though that probably the best moment of all though was a few days later, I was standing right near the office and there was probably four or five, maybe six people hanging out at the front of, and one of them was Randy Jackson, my buddy from American Idol, because Randy and I had worked together a lot with Neil Sean back in the day, and we're all hanging out chatting, and McCartney comes out walking out of Studio A and he looks down the hall and he sees us all standing there. We all just froze, Randy included. We're all like, we're like, oh my God. And he turns down the hall and looks and sees me, and he goes, Hey, Bob, how you doing, buddy? Good to see you. And then he turned and walked off, and all of the other people standing there just looked at me, went, oh my god, Paul McCartney knows who you are. That was seriously, what a moment for me that was just like, it was just like, oh my God. It doesn't get any cooler than that.

Speaker 4 (00:30:38):

Yeah, that's amazing. I'm seriously jealous.

Speaker 5 (00:30:45):

There's been a couple of those moments. One was when I was producing Tony ioe from Black Sabbath, and we had Brian May guesting on guitar, and I'm sitting at the console and Tony i's on one side and Brian Mays on the other side, and I'm like, geez, don't these guys know I'm just this kid from Nebraska. It's like, so yeah, I've had a of cool moments over the years.

Speaker 4 (00:31:14):

Where do you go from there?

Speaker 5 (00:31:16):

Well, the sad thing is, and you guys know this as well as anybody who is self-employed, the truth is, is the second a moment happens whenever you have a number one record or whatever, a huge hit the second, you have about 10 seconds to enjoy that moment. And then it's all about, okay, what am I going to do next? What's my next thing? How am I going to beat this? And I think that sort of sums up my view anyway of I'm competitive, but I'm competitive primarily with myself. I try not to be competitive in that ugly kind of way, but just I love to push myself to always, what's the next thing? What's the coolest? And again, I just turned 60 and this Red Sun Rising record we had back-to-back number one songs, and the truth is this last one was pretty special for me to have number one records at 60 years old. For me, it's like that's pretty cool to stay intense and relative and current at 60 to me was that felt good. That was one that I actually spent a minute and soaked it in as opposed to just next thing, next thing. So that was cool. So

Speaker 3 (00:32:52):

How do you keep on the cutting edge? Since technology is always changing, markets are always changing. I mean, what's cool three months from now is going to be completely different than what's cool now, and every single demographic and niche market has its own life cycle and changes, and it's so hard to keep up with everything going on, neither less a single genre. What's your trick?

Speaker 5 (00:33:11):

Well, number one, I mean, I do try to stay from a technical side of it. I do try to stay as contemporary as possible. I try to make sure, and this is not a dig in any way to some of the engineers from the other time periods and stuff, they sort of brag about their time period and their technology of that moment, but haven't evolved. And my thing was, I've been making records in, let's see, seventies, eighties, nineties, 2000, 2005 decades I've been making records. And in those time periods, they've all had sort of evolutionary growth and spurts that, and what I've tried to do is make sure that I always was on the front edge of the new technology, and so I never felt like I got caught with my pants down. I was like, oh, I don't know that technology. I've always tried to be first in line to try new stuff, but granted, there's a point where you realize, okay, I need to understand what piece of gear is pivotal in a transitional change, in an evolutionary bump. What is a pivotal piece of gear versus the minutia? You can't get stuck spending a whole bunch of time on things that aren't part of the evolutionary jump. So it's making sure that you're smart enough to see the difference between, oh yeah, that's just another program, but it probably is not going to be around that long, versus like, wow, that's something that will be used every day. And that's a key piece of gear that really has an effect on things. So

Speaker 2 (00:35:05):

It's important to stay on top of what you determine as to be Pivotal gear or pivotal software, which I agree with. I think now especially more than ever, we're getting thrown so many things like

Speaker 5 (00:35:22):

Just

Speaker 2 (00:35:23):

15 minutes on Facebook and you'll see 10 ads for 10 different software things. So it's like, what do you pay attention to?

Speaker 5 (00:35:32):

Exactly it. It's realizing now what's going to change my life? What's going to be something that's like, wow, I want that piece of gear. That's something that really is going to be, but don't forget, I mean, part of the deal is once you have jumped made the leap, you also realize the similarities in a lot of things. So when you look at something, you go, oh, okay, I understand the fundamentals of this, even though some of it's just literally it's protocol or what is it about this piece that, oh, okay, but so many pieces of gear in terms of even software, if you run Logic, if you run Nendo Pro Tools, whatever, they all have such similarities. Pro Tools is my main sort of system that I run, but I also have an entire second system here where I do sound design and all the soft sense in a different a Mac guy, but I have a PC system that's running New Window that has all of these other pieces of gear and we run, essentially it's having a system that is completely fully loaded with everything you've ever dreamed about, plus all of the gear in the studio, the essential outboard gear stuff too.

(00:37:03):

And as far as music goes, recognizing who's the one that's actually, it's almost the same recognizing the band that's making an actual leap. Generally the way it works is one band's the actual leaping band, and then there's a whole bunch of other bands that are being influenced by the band that's making the leap. And so it's understanding the same principle, the same concept of saying, okay, well who is it that's really being fresh and doing new stuff? And then who are the guys that are listening to the guys that are making the new step? And it helps a lot because there just aren't enough hours in the day to listen to everything that you should or want to listen to. You just don't have enough hours in the day. So you have to be careful. Definitely. You have to be careful that you're listening to the right things and that you're not getting caught up and listening to something that is just derivative of what the new thing is.

Speaker 4 (00:38:12):

Speaking of new things, not new anymore, but it was new once I read that you were a consultant with the original Pro Tools design team, and just wondering what that experience was like and how it feels.

Speaker 5 (00:38:25):

Actually it was before that. See, I'm even older than that. It was actually way earlier than that. It was a program called Sate by Hybrid Arts, and that was the actual, they were one of the first ones out of the box with that technology. And I did beta testing on that. I also actually did a lot of the beta testing on flying faders too. There was a studio in Hollywood that I worked at a lot, and Flying Faders came in and put a system in there, and we traded that system for daily updates on software issues and stuff. But I don't know quite how that Pro Tools thing started, but it actually was predated pro tools.

Speaker 4 (00:39:21):

So that's a myth out there about the pro tools thing.

Speaker 5 (00:39:24):

Yeah, that is a myth, but I would say that all of us were included in that concept. It wasn't a direct hands-on thing. I was with the Sym Mate and the Flying Fader stuff. This was more of, there was just a brain trusts of people that were all like, Hey, dude, what should we do here? I think part of where that came from was both the Sym mate, but also I was the first one in the US to really work on the CMI Fairlight. Do you remember a box called the Fairlight? I

Speaker 4 (00:40:03):

Do, yeah.

Speaker 5 (00:40:04):

And I was the first one in America because the first people to ever get it in the states was the village recorder. And this probably would've been 1979 or 80, somewhere around there. And the owner of the studio, Jordy Hormel had brought it back from, I think it was created in Australia or wherever, but they had brought it back and they had this giant box, and they were all like, shit, now what do we do? So I had worked there a lot and I was really good friends with all the house engineers and the tech staff there, so they called me up, I was a keyboard player. It's like, well, let's get Bob over here. He will figure it out. And so that was more of a case of us just sort of, let me say, that to me was really that epiphany moment for me because I played a lot of instruments, but I was limited in my mind to the degree of accuracy and the precision that I wanted for performance sakes.

(00:41:14):

And that was that first moment where I was like, oh, wait a second. So I can play a bass sample, I can play a kick drum sample and I could build drums. And that was a real pivotal, and I remember that it was yesterday. It was like, holy shit, this is the new world. This is the new world order. Because this sort of before that, I had friends that one of my buddies, Carl Richardson, who had produced with Albi Gluten, all the Bee Gees records, and he was telling me about, he invented one of the earliest drum machines, and he had figured out if you took a click, that old black metronome with the little light on top, and he wired the output of the light to a solenoid motor with the electrical pulse and then mounted it on a thing in front of a kick drum, and that was the bee gee sound. That was actually, it was clicked with a solenoid motor with that beater head on it hitting the kick drum. That was the early,

Speaker 4 (00:42:29):

That's the original drum machine. Wow.

Speaker 5 (00:42:31):

Yes. Yeah,

Speaker 4 (00:42:34):

So it's actually a drum machine.

Speaker 5 (00:42:35):

Yeah, literally a drum machine. Wow.

Speaker 4 (00:42:38):

I had no idea. That's so cool.

Speaker 5 (00:42:42):

That's the beauty of all of this back in the day, especially because we'd just be sitting around a room and somebody go, God, I wish we could do this. And then there was some brain guy in the corner going, if we did this, we could probably make that work. And they were like, dude, let's do it. And then we'd sit around and figure out how to make it work. And I just love that sort of creativity, and that's one of the things I think is tough today because we all sit around, we want to have the next idea, the next big idea, but it is just so tough because there's so many ideas and so many things, and it's difficult. That's a tough one.

Speaker 4 (00:43:35):

Do you primarily work inside the computer now or do you do the hybrid thing?

Speaker 5 (00:43:42):

I have dangerous audio and I do a breakout, but it's a modified breakout. It's not a console as much as it is just a breakout box essentially. But even that nowadays I'm actually thinking about, I want to figure out how to do both. So I can just go back from being, I want to be able to be completely in the box and then have also the ability to break out. But also I still, part of what I still love is having all my needs and the APIs and focus rights and things. I mean in my 1176, you can never go wrong with that and the stressors and stuff, and I don't want just the UADs or the ways plugin versions. I like old school combined with new school. I mean, that to me is really the best of both worlds. It allows you to have all of the tech, I mean essentially probably where I'm going to head in the very near future is to be completely in the box, but creating all the inserts where I can just grab an insert and boom, there it is.

Speaker 4 (00:44:59):

Do you feel that, just based on everything you just said about how creative it was before the computers took over the world of music, do you find that working with computers limits your creativity, or do you feel like it boosts it? And I'm just curious. We have a whole generation who don't know anything but working on computers.

Speaker 5 (00:45:24):

I actually think it boosts, and I'll tell you why. Because the problem a lot of times was in the old days, I would have the idea, but I couldn't facilitate the idea. Nowadays it's like I'm not particularly limited that much. I have the ability to kind of come up and create whatever I can dream of. I can sort of my next biggest thing, and this is going to be one of the truly next biggest quantum leap, I feel limited by the stereo width of a track. My next biggest thing is when are we going to get our jacks to our brains so we can go directly in,

Speaker 4 (00:46:14):

I'm sure at some point.

Speaker 5 (00:46:15):

Yeah. Well, that's what I'm saying to me, and I don't know if I'll be able to live long enough to see that, but that's the true dream for me is escaping the bounds of our sort of physical limitation. So it only becomes a cerebral one. So everything is, so remember when we were first messing with 5.7 0.1 mixes, and that to me is ultimately it's being able to mix directly to our brain. So sorry, my sci-fi part is taking over, but I think that is probably the future. So actually you mix for the brain and you mix with a completely new concept. But trust me, the cool thing about it is I'm sitting here talking about it, but there's some dude in a lab who's going, we could do that. It's like, so that's a beautiful thing.

Speaker 4 (00:47:20):

I'm sure there is. I feel like at some point that's where it's headed. I've read things about that too.

Speaker 5 (00:47:27):

Yeah, I mean, my thing was it's like I just wanted to live long enough to be able to, because talking about being able to download our consciousness and all things, and I just want to see if I can live long enough that I can get, so I can be able to download myself. Some of that is purely egocentric, but some of it's like, wouldn't it be cool to be able to bypass our limitations? I just think that would be pretty cool. An

Speaker 3 (00:47:56):

Army of

Speaker 5 (00:47:56):

Yourself get shit done. Actually that is true because as I get older, I realize something I really want to engineer a little bit less and mix a little bit less and hand things off. The problem is though, is like I know what I want and I know how I want it to be. And sometimes it's frustrating to, dude, that's good, but it's not, ah, let's try this. So yeah, that would be the advantages in having that is the ability to clone like that. Then I could, Bob, why don't you do this? And I was like, I'm already on it. So you edit drums,

Speaker 3 (00:48:41):

I'll track vocals and you mix,

Speaker 5 (00:48:43):

Dude, see, that's it. It's like all together, boom. There it is. Love that.

Speaker 3 (00:48:50):

I'm already signed up and in queue, so

Speaker 5 (00:48:52):

I'll tell you who to call. Yeah, exactly. Yeah, exactly. Make that happen. Just

Speaker 4 (00:48:58):

Imagine what we could get done if that was possible.

Speaker 5 (00:49:01):

I know, but

Speaker 4 (00:49:02):

Here then, yeah, I'm sitting here thinking it through,

Speaker 5 (00:49:04):

Right? But then the next problem is do we really need to hear all that extra music? Because that's the next curve, I think is one of the things that we didn't talk about that much, but it's kind of been important is back in the day, singularity was more important. The individual was so much more important because we didn't have the same level of saturation. Now there's literally thousands and hundreds of thousands of bands and artists, and every single day it's like, my daughter sings, right? It's like, oh, really? And so to me, that was one of the beautiful things about back in the day, you really did have to be good. You really had to be better because it was so much harder to get there. And that was some of the beauty about it was that I love the fact that you actually had to make your dream come true. Today it's a different world. It's a different

Speaker 3 (00:50:17):

World. So how do you deal with the new world and when the musicians aren't really bringing the thunder and struggling and today's crop isn't quite as good as the old crop, how do you deal with that as a producer?

Speaker 5 (00:50:27):

That is truly one of the most toughest issues and problems that we're facing every day, is the dumbing of our music, the dumbing down of our music. And that's really what it is. And it's very frustrating because having lived through time periods where it really was about being special, and even the worst guy was still much better than a good guy in today's world. And so the hardest part about today is back in the, I would say in the nineties and late eighties and stuff, when the guy couldn't cut it, we made a phone call and we got another musician who was badass who could come in and nail it. All those records that you hear that you were like, oh my God, I love this record and that record. And then years later you find out, oh yeah, actually that wasn't their drummer, that was Mike Baird or whoever.

(00:51:31):

It was like all these other drummers that would show up and guitar players and bass players. And nowadays, my son who he actually, my son played drums on the Red Sun Rising record. My son is totally a badass player, and between him and myself, we pick up the slack sometimes we just simply have to edit. And my son's actually my main assistant now, and he does all the pro tools editing, but he also programs and plays and everything. And so in this environment, I try always, I really try to have it be the band themselves. I try for it to be as organic as possible because that always just for the most part, that leaves you with the best product, something that's real and organic, but which in these situations rise all the time. In this case, then we have to do whatever needs to be done, so

Speaker 4 (00:52:41):

You just get it done.

Speaker 5 (00:52:43):

Well, that's one of my, how possible. Yeah,

Speaker 4 (00:52:46):

That's what we do.

Speaker 5 (00:52:47):

Yeah, that's one of my lines that gets used all the time is like, I don't care how we get there just so long as we do.

Speaker 4 (00:52:54):

Well, it is what it is. I mean, back in the day, they had session musicians as a regular thing. Nowadays it seems like the producers are taking on more of that session musician role.

Speaker 5 (00:53:07):

Exactly.

Speaker 4 (00:53:07):

Interestingly enough,

Speaker 5 (00:53:08):

Absolutely.

Speaker 4 (00:53:09):

But I feel like that element doesn't seem like it's really changed. There's always been that safety net of somebody available who is that much more badass an instrument than the band members just in case.

Speaker 5 (00:53:24):

Well, yeah. I mean, this is not new. I was a session player back in the

Speaker 4 (00:53:31):

So you were the guy?

Speaker 5 (00:53:32):

Yeah, I was the guy that used to get the call to come in and fix. And back in the day, it's like the same thing applies today as it did back then. It doesn't matter how we get there just so long as we do, because at the end of the day, my job is to deliver the record. So at the end of the day, however we get there, we just got to get it done. And you're right, it really hasn't changed much since the old days, whether it was the producer or it was the stable of players that he knew or the top dudes. There were lots of guys that just got a lot of work. They look at, did you ever see the movie Wrecking Crew? That was such a great example of this very thing that we're talking about, and that was in the sixties. I recommend that movie highly. Actually, it's interesting because my son's grandfather, my ex father-in-Law Bones, how he's in that film, he produced The Mama's Pop is Fifth Dimension, Elvis, the Turtles Hurdles, just a gazillion of huge bands. And one of his bands, the association, they were talking about that very thing with the wrecking crew. He was being interviewed about calling them up and having them come in and do the record. So yeah, it's pretty interesting

Speaker 4 (00:54:57):

Actually. I'm going to watch that now. My curiosity has peaked.

Speaker 5 (00:55:01):

Definitely. Trust me. Yeah, you're going to want to see it. It is really interesting how they just talk in the, that's the way it was, man. You just came in, played the record, didn't think about it, did it. And what's crazy is one of the most prolific session bass player in the sixties was a woman, Carol Kay, people don't realize it, but from these boots, these boots came walking, and that's her playing bass on that. And from Hawaii 5.0 and all this stuff, it is so worth seeing the movie. It's very clever,

Speaker 4 (00:55:42):

Very cool wrecking crew.

Speaker 5 (00:55:43):

Yeah.

Speaker 4 (00:55:44):

Cool. I'm going to actually check that out tonight.

Speaker 3 (00:55:47):

Yes. So if you had to attribute all the success you've had in your career to three specific things, what would they be in your opinion? Well, the three bands or three artists or just three things that you do. Routines, rituals, habits, attitudes, anything. What's the secret sauce?

Speaker 4 (00:56:04):

Mindsets?

Speaker 5 (00:56:06):

Probably number one. I'm kind of crazy maniacal for energy. It's like I want to feel that record coming out of those speakers. And that's one of the things that I try to always sort of keep an eye on is that feeling that I'm being punched in the face emotionally, whether it's an acoustic soul alternative artsy fartsy record, or the most crushing heavy record. I just want to emotionally feel like I'm getting punched in the nutsack because that's really what, whether you listening to James Taylor or Mega Death, it doesn't matter. It's about feeling the energy come across that. And I am absolutely maniacal about songs and every artist that you'll ever talk to that I've worked with over the years is like, I'll tell you this, and this is, I say it to every single band, but it's the same line and it works every single time because it helps them understand it. I'll start by saying, what's the cure for a shitty snare drum sound? Great song. Thank you. Thank you. A hit song because who the fuck cares what the snare drum sounds like if the song's a hit?

Speaker 3 (00:57:36):

Thank you for saying that because every month I feel like I say that about mixing. I mix a lot of songs, Bob, I'm like The 500 club a month. No,

Speaker 5 (00:57:46):

I know. Sorry. A year. Yeah, you the man. I know that. Yeah,

Speaker 3 (00:57:51):

That's great. It's just all about it doesn't fucking matter because you hit play and either your mom likes it or she doesn't. I mean,

Speaker 5 (00:57:59):

Let's be honest. That's exactly right. It's so true. And that's the preach is that, Hey, guys, you know what, yes, we all care what the snare sounds like, but at the end of the day, the snare is not what gives it longevity and the snare, it's like the snare. It is just a thing in there. It's all about the song and then understanding, making sure that the singer sings the song with the passion and the energy and is connected emotionally to it. And if you get those two things right, you'd be surprised how easy this business is. It really is. If you dial those two things in, you'd be surprised how everything lines up for you.

Speaker 3 (00:58:54):

I hope everybody listening to this goes back and rewinds and listens to you say that 15 times. It ingrains it into their skulls because that is tattoo. The best advice I think I've ever heard.

Speaker 5 (00:59:04):

Well, like I said, there are few advantages to doing this for 40 plus years, and that's one of them is realizing really where to put your priorities. And it is like if you really make sure the song is in place, the artist is connected and singing and basic fundamental engineering skills. And the beautiful thing is nowadays the playing field has leveled out so much because we all have essentially access to pretty much the same thing. So that's the good news. Back in the day, we were limited because not everybody got to go into the studio and they didn't get to go into Henson record plan or wherever. It's like they didn't get to go into those rooms. But nowadays, dude, I move, my setup is in my house. Everything you've ever dreamed about in your life is sitting right here in my house. So it is like the playing field has pretty much leveled for most people because even just a good pro tools rig with a bunch of plugins that gets you to the starting gate, then it's about the song and the singer,

Speaker 3 (01:00:28):

I'll tell you something, I noticed when I came out to your place, Bob at Nam, and we hung out. I was actually shocked to walk into your kitchen when I had to use the bathroom and there was the drum set all micd up, and I walked back into the studio and he was playing, and it sounded fucking awesome. So there you go. You can mic drums in your kitchen if you know what the hell you're doing.

Speaker 5 (01:00:45):

Well, that was a beautiful, happy accident. It's like I was doing this kind of quirky small alternative record, and it's like I just wanted to do kind of a cool small drum kit overdub thing. And I was like, oh, you know what? Let's go in the dining room. Let's go into the dining room, put some mics up, see what happens. And I heard it back and I went, my dining room sounds fucking amazing. I love it. It does. Okay, great. So then as always, then I had tie lines put in and it's like I had cameras and all this shit put in because whatever I do, I usually take too far anyway. But anyway, the point is is that now, because I never set out at this studio my environment to have a drum room, I always still like going to Hanson and wherever to track drums. But then I realized that my drum room sounds great, so okay, I'm never leaving the gates anymore. So now it's like I don't even open the gates. I just stay at home. So it's all good.

Speaker 4 (01:01:57):

Speaking of drum rooms, what type of live rooms do you prefer? Or does it differ from record to record? I

Speaker 5 (01:02:04):

Mean, I would say this, I don't super small rooms and I don't super big rooms. I tend to always like a room that's kind of in the middle. But for instance, I realized something. It's really more about the angles and just the energy of the room because my dining room, we have nice hardwood floors, we have a vaulted ceiling and we have this giant brick fireplace in the dining room and all this brick and stuff. So it's these weird angles combined with the hardwood and the stone creates this great, not a lot of weird bogie reflective. It's all kind of, and that's kind of in general what I like in a room. I don't like it too small, but I really don't super big rooms because to me it's just all it is is energy kind of going out and dissipating and not sort of collecting the energy and getting it on the mic. So

Speaker 4 (01:03:17):

Big ass rooms become totally uncontrollable, in my opinion.

Speaker 5 (01:03:22):

Yeah, it's one of those things that somebody go look how big my room is, and that's just more work. I'm going to have to close it down to not have all that fucking extra noise floating around.

Speaker 2 (01:03:37):

I actually had my first drum room, well, my first drum room that I owned was in my dining room of my house, and it had a fireplace in it, and it had some pretty open doorways. The doorways were probably around, I would say five feet wide and nine feet tall. So it actually was perfect for recording drums, oddly enough.

Speaker 5 (01:04:01):

Yeah, well that's the same concept is here, is that it's weird because it has more to do with kind of an openness and a non square, not sort of non-reflective walls and stuff. So it's really more about that. It's the angles and the quirkiness that make it sound so cool. One of the coolest drum rooms ever is Townhouse Studio two, which is now an apartment building in London, but used to be one of the coolest rooms. That's where they did everything from Zeppelin and Stones. And that's, remember in the air tonight, the Phil Collins, that's where they recorded that. And it was was a hardwood floor, weird angles, really high ceilings and lots of brick. And it's surprising how that equation equals great drum sound. So I love that. I think that's cool.

Speaker 4 (01:05:02):

Question, just out of curiosity, do you ever still record the tape?

Speaker 5 (01:05:07):

Funny you should mention that. As a general rule, I would rather have all of my teeth pulled then go to tape, but I just did the new airborne record in Australia, and that was one of the things the guys were like, dude, we want to go to tape. We want to old school, just make it badass. And I'm like, really? And I got talked into it and it sounded great. And it's more to do with the hassle than it is. The quality is great. It sounds great. I mean, it definitely has its own thing, but it was more of, at the end of the day, it was something that really worked good for them. It was just an organic thing that was like, yeah, this is badass. And plus, I had Mike Frazier come in and engineer it for me, and that guy's badass, and it was a perfect storm of all things tape and him, and so it all worked nice.

(01:06:14):

But as a general rule, no, I would definitely not. I don't like tape, but part of it is philosophically tape adds things. Tape moves things around, and every time it passes by the heads, it's losing stuff. And my theory is that my job as an engineer is to be able to engineer into the sounds all I tape, hard drive, whatever. It's just the storage medium. That's simply the place for me to store what it is that I've engineered. So that's why I tend to prefer pro tools now. It sounds so good. It just comes back exactly what I put in, and that's what I really want. I don't want it to be altered, otherwise I would change the sound to be that.

Speaker 4 (01:07:10):

So you're sick of a storage medium that's degradable.

Speaker 5 (01:07:13):

Yes. Thank you. Perishable. Yeah, well played young man. Well played. Yes, that's exactly right.

Speaker 4 (01:07:21):

I just think it's really, really interesting because we've talked to lots of people at this point on this podcast, and I just find it remarkable how much you've adapted to the world, and I really think to the new world of audio technology, and I really think that that's part of a big reason for why you've stayed so relevant, continued to evolve. We've talked to some guys who haven't necessarily felt the same way about it, and a lot of their hits were maybe in other decades and didn't continue on and stuff, but I think there's something to be said for embracing the future. You can't fight it. It's coming.

Speaker 5 (01:08:06):

I was going to say, for me, the main thing is I was never afraid of it. I was never afraid of anything, and because I felt that that was one of my responsibilities as a producer and someone who made music is I wanted to be the opposite of afraid. I wanted to embrace the unknown, and that's where the fun is at. But understand something, the reason why I can be like that is because I'm able to back it up with years of songwriting and playing and engineering, and so there really isn't a lot that I can't do. So that really helps in the attitude of being bold and fresh is that I know it's going to be okay. I know I'm always going to pull it out, so it doesn't matter what we do. I'll be okay. It's going to be okay. The

Speaker 4 (01:09:02):

Medium's just a medium.

Speaker 5 (01:09:03):

Yeah, they're all, it's just realizing that it's just buttons to move and push and fade until I get what I want, until I get it to sound the way I want it to sound.

Speaker 2 (01:09:18):

I really love the practical approach or the practical way of thinking about this industry or this thing that we do because so many people get caught up in having the coolest mic or the coolest compressor, but who gives a shit?

Speaker 5 (01:09:33):

Yeah, the person

Speaker 3 (01:09:35):

Who owns it.

Speaker 5 (01:09:38):

You know what? You're absolutely on the money about both those things because the guy that gives you the biggest speech about a particular box is the guy who owns that box and he's telling you about his box that is the secret to his shit. Well, the truth is, there isn't any secret to what I do. I just wake up in the morning and I go out and I make music. There's no, no magic bullet to any of this is just make music, have fun, love it, be passionate about it. It's all good. I mean, there it is, right?

Speaker 1 (01:10:14):

Boom.

Speaker 5 (01:10:16):

Boom. Shots fired. Yeah, actually, that's one of my terms that I use a lot. Boom, because that's just it. What else is there? It's a mic drop. Thanks. Boom. Yeah,

Speaker 4 (01:10:28):

See you. Thank you. Goodnight. One last question because we're coming here to the end of our time for this is do you have any final bits of advice for audio engineers or songwriters or film scores or session players or just anybody trying to make a living in audio and music in 2016 and on?

Speaker 5 (01:10:49):

Actually, I do, because that's a question that I get asked fairly frequently, and it's pretty simple. My theory is say yes to everything. Say yes, no is really not. It shouldn't be in your vocabulary. It's say Yes and then figure it out. It's like people ask me, it's like, dude, man, you did that record. That was the dumbest record ever. Yeah, but you know what? It may have been the dumbest record, but now it's part of who I am, and it's okay, and it ain't no big deal. I don't get really caught up in trying to be super cool or have everything that I do be so badass that it's like if you say yes to everything, that's how you build up a life of music and creative ideas, and those are the things that end up at the end of the day helping you be truly great at this is the fact that you've done it enough times in bad situations and good situations and weird situations. I've always said part of what makes me good at what I do, the therapist, part of who I am is that being the teacher, the therapist, the songwriter, all of those things. If you say yes to everything, that means you're learning, you're evolving, you're working, you're making it happen. Do not sit around your fucking bedroom all day waiting for something to come to you. Go out and make it happen. Go.

Speaker 2 (01:12:40):

Yeah, especially as soon as something does come, don't say no. Yeah,

Speaker 5 (01:12:43):

Because I see people that it's like, well, I didn't think that was cool. At this point in my life, I can say no, but that's not how I started. I didn't start out by saying no. I started out by saying yes, and I think that is so important. Don't get caught up in the wrong things. Don't try to fucking be so cool that you're trying to OutCo the next dude. Embrace everybody. Embrace the different ideas, all that stuff. I don't want to sound like a hippie, but I do feel the importance of just keeping open, be open, be creative. It's like how many times have you been in a room where some guy is like, yeah, man, that R just is really fucking gay. It's like, and I'm just like, how about you? Shut the fuck up. Shut up.

Speaker 2 (01:13:43):

Love it.

Speaker 5 (01:13:44):

You do something. You do something that's worthwhile, then you can talk about something, but right now you got to earn that right to say anything. So anyway, sorry, I got on my soapbox again. Sorry,

Speaker 3 (01:14:01):

Bob. Thank you for coming on. That was absolutely amazing and I'm hoping we can do it again. Sometimes we know you are super busy, but that was quite an enlightening hour.

Speaker 5 (01:14:10):

Well, it's my pleasure, gentlemen, and I hope I've been helpful in some way. Like I said, part of my job at this point in my life is passing as much knowledge on as I possibly can to people and do everything I can to make sure that I am able to earn all the amazing things that have come my way, so thank you guys.

Speaker 4 (01:14:33):

Thank you so much for coming on, man. All good, my

Speaker 1 (01:14:35):

Friend. The Unstoppable Recording Machine podcast is brought to you by Focal Audio, the world's reference speaker. For over 30 years, focal has been designing and manufacturing loudspeakers for the home speaker, drivers for cars, studio monitors, for recording studios and premium quality headphones, visit focal.com for more information. To ask us questions, make suggestions and interact. Visit urm.academy/podcast and subscribe today.