Jamie King: Producing Between the Buried and Me, his single session workflow, managing band psychology

urmadmin

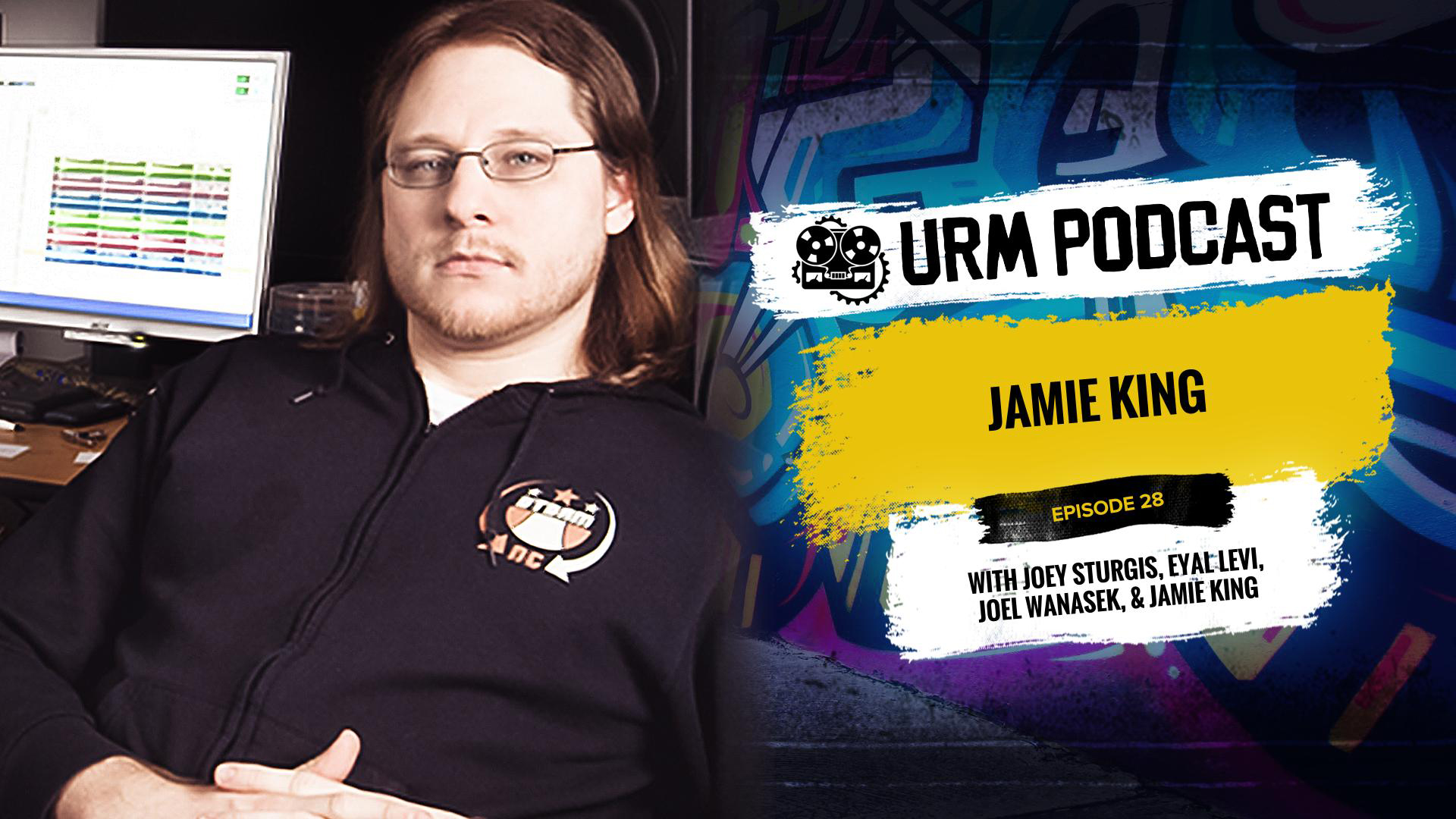

Producer and engineer Jamie King is best known for his long-standing relationship with progressive metal titans Between the Buried and Me, having worked on nearly their entire catalog. Operating out of his North Carolina studio, The Basement, he has become a go-to producer for technically demanding and forward-thinking bands. His credit list includes acclaimed albums from The Contortionist, Scale The Summit, and Wretched, establishing his reputation for capturing complex musicality with clarity and power.

In This Episode

Jamie King chops it up with the guys about how he built his career from the ground up, starting in his parents’ basement and becoming the go-to metal guy in his area. He shares the full story of how he linked up with Between the Buried and Me and managed to keep that relationship strong even after they got signed. Jamie gets into the nitty-gritty of his workflow, including his unusual method of tracking an entire album in a single Pro Tools session and the pros and cons of being self-taught. He also discusses the delicate art of managing band psychology—knowing when to facilitate their vision versus when to step in, and how to deal with artists who want inhuman perfection. From specific mic techniques for drums and bass to the ongoing debate between real amps and digital modelers, this conversation is packed with real-world advice on adapting your process to serve the song, the client, and the ever-changing landscape of modern production.

Products Mentioned

- Avid Pro Tools

- Fractal Audio Axe-Fx

- Kemper Profiler

- Line 6 POD

- Joey Sturgis Tones Toneforge

- Mesa/Boogie Mark V

- Boss ME-50

- Marshall JVM

- Neumann U 87

- Shure SM7B

- Shure SM57

- Shure Beta 52A

- Sennheiser MD 421

- Celestion Vintage 30

Timestamps

- [1:57] How Jamie started his long-term relationship with Between the Buried and Me

- [3:23] Why being the only local engineer who “got” metal was a huge career advantage

- [5:44] Keeping a band’s loyalty after they get signed to a label

- [10:04] The pros and cons of being a “facilitator” producer vs. an interventionist one

- [11:05] The upsides and downsides of being a self-taught engineer

- [13:30] Unlearning bad habits from the analog days for a digital workflow

- [14:16] Jamie’s unique workflow: recording a whole album in one Pro Tools session

- [17:47] Pros and cons of the single-session workflow for editing and mixing

- [21:20] How he learned to cut EQs more in the digital realm vs. boosting in analog

- [25:17] The debate over committing to sounds vs. keeping options open

- [29:20] The psychology of “good enough” and not getting lost in perfectionism

- [32:10] Famous mistakes on classic rock albums (like Guns N’ Roses)

- [33:02] Deciding between a natural drum performance vs. heavy quantization

- [38:10] How to handle a band that isn’t skilled enough to achieve their “natural” recording goals

- [40:06] How Joey and Joel handle artistic disputes between bands and labels

- [44:39] Jamie’s creative input (or lack thereof) on BTBAM’s complex songs

- [49:45] Micing techniques for snare, including using a side mic

- [55:44] The divide between younger bands (amp sims) and older bands (real amps)

- [59:06] The surprisingly simple clean guitar chain on The Contortionist’s album

- [1:02:55] Jamie’s approach to tracking a huge but clear bass tone

Transcript

Speaker 1 (00:00:00):

Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast, brought to you by Mick DSP professional audio plugins. For over 15 years, Mick DSP has continued producing industry acclaimed and award-winning software titles. The podcast is also brought to you by Slate Digital, all the Pro plugins. One more monthly price, and now your host, Joey Sturgis. Joel Wanasek and Eyal Levi.

Speaker 2 (00:00:31):

Hey guys, welcome to the Joey Sturgis Forum podcast. I'm Joey Sturgis, and with me as always is Joel Wanasek and Eyal Levi, and today we have a special guest, Jamie King, the man, the legend. Jamie King is the man, the legend,

Speaker 3 (00:00:46):

The redneck.

Speaker 4 (00:00:47):

Thanks for being with us, man. I've been following your work for well over 10 years at this point. I think for real. I think that I heard that early between the Buried and Me stuff, maybe 2005 or something.

Speaker 3 (00:01:03):

Gotcha.

Speaker 4 (00:01:04):

Yeah, so I'm stoked to have you on here. I've been a fan for ages and I just want to say that I love the most recent between the Buried and Me, the way it sounds so natural and big and just sounds like a real band yet modern.

Speaker 3 (00:01:21):

Yeah, it has a lot to do with Y's. Rin also, so he's actually the guy who mixed it.

Speaker 4 (00:01:26):

Yeah, but you had to record it. He's a great mixer too. We're actually having him coming on. Awesome, awesome. Love it.

Speaker 3 (00:01:32):

We'll definitely have to check that out. Well, I'm definitely honored for you guys to have me on. I mean, like I said, I look up to and respect and reference all your works oftentimes to try to get tones for stuff that I do, so

Speaker 2 (00:01:46):

That's awesome. And I just want to say that congrats on Snagging one of the coolest bands to record, I

Speaker 3 (00:01:53):

Think. Oh yeah, yeah, I got lucky on that one.

Speaker 4 (00:01:57):

That brings up a question that a lot of our listeners bring up. I'm going to just phrase it my own way. I've noticed that a lot of producers who work with bigger bands tend to have found that one band that got big and that helped spawn their career. Not that they wouldn't have had a recording career anyways, but usually there tends to be that one band. How did you end up meeting them? How did you cultivate that relationship? What kept it going? How did you keep them coming back to you?

Speaker 3 (00:02:29):

I was doing a live sound I guess in the late nineties or whatever, early two thousands, and I did sound for prayer for Cleansing, which was Tommy and Paul's band before between the Bearing to me, and they had heard my band, my old band Swift or my recordings, that band, which was the band I did in my first multi-track recordings and at the time it was the first local stuff that was even kind of listenable. The audio engineers around this area were just terrible or just not affordable at all. So I think that was the key thing. I mean, I think the main aspect is I was young and into the style of music they were doing and understood the tones that they were going for. Back in the day, a lot of local engineers, they were just older guys who could afford the expensive equipment back in the day and they just didn't understand metal or younger generations of music.

Speaker 4 (00:03:23):

We had Kurt Baloo on here a couple months ago and he basically said the same exact thing that you just said, that the way that he got his career going was by filling that niche because the guys with nice studios in his area didn't understand the style at all, so either your options were go to a horrible, horrible place or go to one of these super nice places and both were going to get you a bad result. So he just figured he was going to fill that niche.

Speaker 5 (00:03:54):

Well, I'll echo that too. That's how I got started. There was no, I mean if you wanted to pay 70 bucks an hour, you would get what would be the worst local band recording you've ever heard in the town that I'm from.

Speaker 3 (00:04:04):

Exactly.

Speaker 5 (00:04:05):

And I was the only guy that could do metal. So if I was charging like 25, 30 bucks an hour at the time, you kept me booked because no one could really do that kind of music and if they could, they were so outrageously priced that it just wasn't affordable for any bands.

Speaker 3 (00:04:21):

Yeah, that's exactly, that's why between the Barry, he chose to record with me. I think I was working on my parents' basement doing live recordings with a dad. Some of the cheapest stuff that you could get at the time. It is all I could afford, but I could keep, my rates were, I think I started at 10 bucks an hour and then maybe we were like 15 bucks an hour and it was all live recording, so there was no production going into it. It was just like bands would come in record for two or three days and the whole total bill was like three to 500 bucks, so obvious demo quality type stuff, but at the time, kind of more raw type productions were kind of in vogue with the new metal movements and the dirty metal stuff that was going on. That was kind of the sound at the time. So I kind of had to step up my game as the demand for more produced products came into vogue or whatever.

Speaker 4 (00:05:14):

That brings up the question then, if that's how you were starting and that's how you met them by being the guy in town that could fulfill their needs, I guess how did you manage to keep that relationship going though? Because I mean, we all know that lots of times a band will work with one guy that's affordable and local, but then once the record label gets into the picture, they get moved over to the producer of choice from the label, but you manage to keep the relationship going.

Speaker 3 (00:05:44):

Yeah, I think there's a number of factors. I think with between the very, obviously we're on the same page musically, we have a lot of the same background in terms of what we listened to coming up and between The Berry and Me are really into surrounding themselves with positive people, people who they enjoy spending time with. It's about the life experience, a large part for them. And there's the element that I'm close by Blake, the drummer lives up the road. Dusty doesn't live too far. Tommy Paul used to only live like an hour and a half from here, so there's that element. The first record with Victory Records or whatever, they did go up to Boston to record,

Speaker 4 (00:06:24):

So it did happen.

Speaker 3 (00:06:25):

I did the first live style record, which was that record came out originally with Life Horse records in Germany and Victory bought that contract out. Obviously they wanted someone who could do more of a produced product, so they sent 'em to Boston to record, and Bt Bam basically cited that as a nightmare experience for them because the guy they were working with, even though he was a super talented engineer, he just didn't understand the music and we tried to talk them into keeping bad takes and didn't understand the tones and basically wouldn't do anything they asked him to do. He just did his own thing and they just didn't like that they knew I am the type of guy who will try to do it what they want to do.

Speaker 5 (00:07:03):

I think that's a great point, Jamie, because I've got a very strong opinion on this because I used to develop a lot of bands and then earlier in my career, a lot of them would get picked and they would go work with some expensive guy and they would always come back to me for their next record and be like, yeah, we hated it. When you develop a friendship and a bond and a certain level of trust as well as a creative balance with that band where you can complete each other's musical sentences, you know what I mean? You just have a chemistry with them.

Speaker 3 (00:07:31):

Exactly.

Speaker 5 (00:07:31):

That's built over a lot of work together. You just know each other as people. You know what to predict, you know what to expect, and that's not something that you can usually get with a band when you're doing one record with them for the first time. So if you've done a bunch of recordings over a period of years with a band that all of a sudden they get signed, then they go to some new producer, they're going to be totally out of their element in comfort zone and they may not get the best result. So I think it's always cool when a band takes a producer with them if they go up the ladder to a major label or a large indie or something like that, and they fight for the team that help get them there because those are the people that they created some sort of magic that gathered the investors in the first place in the project, and that's just one of those things that drives me nuts because you can't replace that magic chemistry that exists with a band. It just is not something that happens right away on day one. It takes time.

Speaker 2 (00:08:24):

Yeah. Another thing that happens to me is I'll work with a band. The album comes out and the fans sort of have whatever their expectation is, and some people will say, Joey ruined this or he changed the band. It's like, no, the band actually came to me and was like, Hey, can we be more like this other band that you did? And I'm like, well, if that's what you need and that's what you want, I guess you're paying me so I have to kind of do it.

Speaker 3 (00:08:53):

Yeah. With me, the client's, the boss, and the reason I take that approach is I got into recording for my own band because we were just talking about just a few seconds ago that I got into recording just because there was no one in the area that was willing or able to give me the tones and things that I wanted. So even though there was studios I was going to and paying 90 bucks an hour and these guys just would not give me the punchy kick drum I wanted or the metal guitars that I wanted at the time, the alternative was huge or rap rock or whatever. That was key for between the berry to me, and they had a specific, very specific vision and they're really big on sound and the way they sound, and I think that's why they come to me. They keep going to people and those people tend to try to steer them in other directions and change their material and for a lot of bands I think that's needed in a positive thing. They need that direction and they need input and they actually want it. But for BT, bam, basically they just want a facilitator or someone to maybe add to what they're doing but not necessarily change it. And I think they know I'm that dude and we hang out and have fun together and I'm local and like I said, in a lot of ways I just feel like I got lucky that they actually like me.

Speaker 4 (00:10:04):

I've noticed that there is, there's some modern metal producers that are really, really good, but they kind of do the same thing every time no matter what the record is. So if the band is terrible, they do the same thing and if the band is great, they do the same thing, which I think is a mistake. I mean, clearly if the band is terrible and they're going to that producer, the producer is doing the right thing by putting them through the surgical reconstruction process, but if you have a band of great musicians with a very defined musical vision and personality and character, may as well do what you can to bring out what they want. They don't need you to fix them, they just need you to, like you said, facilitate them. So here's a question. You said that you started with live recording and things started to pick up a little and you realized that you needed to up your game some, but there weren't many resources back then. There are now, I think. How did you go about getting better?

Speaker 3 (00:11:05):

Yeah, it was tough At that time there wasn't YouTube and other resources of that nature. There were no local engineers I could shadow or anything. Most of what I've learned and most of the, I guess if you call 'em skills or whatever I've developed or just from trial and error, like reading

Speaker 2 (00:11:24):

Amen, brother.

Speaker 3 (00:11:25):

Yeah, I just had no choice. Unfortunately, I don't recommend it because it takes forever. It is taken me 10 years to get where I am now and it's still not where I want to be, but

Speaker 5 (00:11:34):

If I can jump in, there's one major thing about being self-taught that I think is really cool is you develop a very unique sound that way much quicker than you would if you were to shadow somebody and kind of quasi steal other tricks.

Speaker 2 (00:11:48):

Also, a unique understanding. It's like your labor, you connect with it on a super deep level because someone didn't tell you how to do it, you didn't read a book that told you how to do it. You've literally figured it out on your own and I think that's super strong.

Speaker 4 (00:12:07):

Yeah, I got to say though, I feel like even if you do have the good fortune of coming up under somebody or having those things, those positive influences in your production growth, you still got to put in the work either way.

Speaker 1 (00:12:23):

Yeah,

Speaker 4 (00:12:23):

I mean just because someone says cut some nasty frequencies on guitars doesn't mean that you're going to automatically know when there's too many of them or too little of them on a guitar tone. These are things that you need to figure out for yourself anyways, but it does help, I think to have someone tell you that this is something you need to be listening for. Creative Live or YouTube existed 10 years ago. I would've been so happy. Oh,

Speaker 3 (00:12:48):

Absolutely. Oh my God,

Speaker 4 (00:12:49):

Right.

Speaker 3 (00:12:50):

Yeah, I mean having gone through it, I've been doing this for a living for 15 years. There's a lot of bad habits and things that I developed using the wrong gear for the wrong sounds and things of that nature that if I knew then what I knew now, I think I would be further along now. So anybody listening out there, I recommend them check out the creative live stuff or try to shadow someone or get in for an education session with the people who are in the know and at least get the solid foundation for the production style and the sounds that you're going for and then try to develop your own sound from there. I think you do develop your own kind of sound through self-teaching and learning, but you can also develop a lot of time consuming bad habits and things like that. I really personally like I'm still unlearning. I started with mixing board and a rack of gear and a couple of ADATs and there was a kind of different approach and I had to change things. I started in with Pro Tools early, but it's more of an integration type of approach of just editing and still mixing on the board and things of that nature. And I mean there's so many more options in the digital realm now and if

Speaker 4 (00:14:02):

You don't mind sharing, what are some of the things that I guess you've had to unlearn but at the same time, what are some of the things that you've done wrong? Technically wrong, but that actually are pretty cool. I'm sure there's some happy accidents.

Speaker 3 (00:14:16):

I record all my sessions in one session, pro Tools, I've learned how to streamline things, so that works for most of the stuff that I do. I feel like that's maximum efficient.

Speaker 2 (00:14:27):

Hey, I want to say man, that's really cool to wanting to do it. I think I tried it a couple times to do a whole session in one project. I never figured out how to actually get it manageable, at least in Cubase. So I'm curious at least for Pro Tools, what are some of the things you're doing to make it

Speaker 3 (00:14:47):

A lot of what I do, it is got a lot to do with just sharing a bunch of tracks and things, just grouping things and keys and things like that. Most of the people who do a lot of, I guess a lot of MIDI stuff, soundscape production, things like that, a lot of those people will do it outside the session and that's kind what I do. I think I saw in Joey's creative live class where he does things in separate sessions and imports in and things of that nature and that can help keep the Pro Tools session from being crazy. As far as Pro Tools is definitely, I don't think it's the best. I don't think thing for the mid stuff usually I do most of that stuff in a different session and to import any keys and MIDI stuff or so I'm not running a bunch of MIDI stuff or instruments and things like that that'll take up a lot of CPU.

Speaker 2 (00:15:38):

I see. So it's kind of like you have an additional layer by having this Master Pro Tools session that everything ends up being piled into not necessarily the session that you work in and record on and edit in, but it's where you kind of toss in all the little pieces at the

Speaker 3 (00:15:54):

End. Yeah, basically it's like I have a session, it's just all the waves and then any many, many information is generally speaking, bounced worked in another session and bounced in. I don't do a lot of bands that have a lot of that stuff and when I do, oftentimes they just bounce out the stems themselves of the keys or the individual key tracks themselves and I'll just import it and process the actual wave and stuff. So I think that helps and I just started that by accident because with A DAT, you just record until the tape is run out. I didn't realize that most people track separate songs on separate sessions. I just started it from with Pro Tools I just going into,

Speaker 2 (00:16:35):

Hey guys, well half this song ended up getting cut off on this tape, so let's go grab another tape and finish the other half. I have been there,

Speaker 5 (00:16:44):

I used to do it all in one session too and then I went and I did a record with Joey where I had produced and engineered and he had mixed, and I walked in with my session and he's like, what the hell is this? Why didn't you drop these all into single sessions? And I'm like, oh yeah, that's kind of a cool way to do it. I never thought about that, so he converted me over 2008. I've been doing it that way ever since

Speaker 3 (00:17:04):

I've learned. I don't think there's any rules. I think just whatever works for you. You know what I'm saying? For a lot of the bands I am recording lately I get a lot of clients that are big fans of Between The Bury Me of course, and a lot of these people are trying to do concept records or records that flow song to song and it really helps to have everything in one session just because the client knows exactly how the songs are going to flow and you can work with everything in context and there's no guesswork. And plus just little things like I never have to close and open up the session. I can open up one session and leave it open all day and we can just keep recording. I can bounce from song to song and there's no closing and opening things like that, copying over settings or any of that kind of stuff. It helps things be a little more consistent, easier I guess.

Speaker 5 (00:17:47):

I was going to say, I think it's really awesome from mixing and tracking, where I always hated everything in one session is when you're editing drums and you've got 4,000 little cuts in Cubase, we do this thing called slip editing, which is, well there is Beat Detective now, but it didn't happen until Cubase six or something like that. Everybody in Cubase would just cut and then slide the audio within the block and you have 50,000 cuts on a screen and then you bounce everything down and it gets kind of slow on the CPU and can lag a lot or if you're doing a lot of MIDI production and stuff like that you guys are talking about that can really bog you down and be a pain in the butt when you've got 400 open VST instruments and you're still tweaking sounds.

Speaker 3 (00:18:30):

Exactly. Yeah, I mean there's pros and cons to both.

Speaker 4 (00:18:33):

Hey guys, Al here and I just want to take a moment to talk to you about this month on Nail the Mix. If you're already a subscriber, thank you so much, we appreciate the hell out of you, but if you're not and you want to seriously up your mixing game, then you might want to consider Nail the mix. This month we have a guest mixer, Mr. Kane Chico, and he will be mixing Face Everything and Rise by Papa Roach and when you subscribe you get the multi-tracks that he recorded and produced, you download them, you can enter a mix competition with prizes by mc DSB, you get an Emerald Pack version six, that's like a $1,600 software package plus the winner also gets one year of everything bundle from Slate. So really, really good prize package for our mixed competition winners. We've also got a second place package that rules and yeah, if you join Nail the Mix, you also get bonus access to our exclusive community, which is other audio professionals and aspiring professionals just like you who just dork out on this stuff all day and night and love spreading knowledge. It's troll free and so whether you knew or experience, it's a great place to just come talk about the thing we all share, which is a love for audio. So once again, if you haven't subscribed to Nail the Mix yet, this might be a great month to try. You get to learn how Cane Chiko mixed the number one single face everything and Rise wipe Papa Roach, just go to nail the mix.com/papa Roach, that's nail the mix.com/papa Roach.

Speaker 3 (00:20:24):

So both ways, just whatever works for you. I think I've just developed some workarounds to deal with a CPU thing like with doing drone quantizing, I'll just do a couple minutes at a time and consolidate the files and get rid of the unused files as I go and that just keeps the machine from being bogged down and I don't think any of that affects the sound at all. It is just workflow stuff that I personally, I'm kind of glad I do it. I feel like it works well for me and just little things like that. But as far as things for sound, as far as mistakes and stuff like I mess with the wrong mics on guitar tones and on guitar amps and on drums and things and wrong micing techniques and stuff like that, and it's just really cost me a bunch of time trying to figure out how things work. Plus from the analog days of running into a mixing board and ada, so I used to EQ things going into the recorder with analog boosting and cutting can yield some positive benefit to the tone. But in the digital realm, I feel like a bunch of boosting EQ and stuff actually just makes things harsh and I had to learn to cut more so in the digital realm as opposed to the old school boosts in the analog realm. So yeah,

Speaker 5 (00:21:38):

I'm with you there.

Speaker 3 (00:21:39):

It is weird how I really feel like they're different ones. Even the emulators, they feel different and act different with the actual signal than the digital.

Speaker 4 (00:21:49):

I think it says a lot though that you've taken the effort and time to learn how to adapt to the new system because man, a lot of guys who started analog, they don't adapt to the digital realm and it's possible to get great results in the digital realm. You just have to treat it like a different beast like you said, but hey, that's why you're recording cool stuff and still a relevant guy out there because adapted to the modern age. So here is something that I'm wondering back on the one session for everything. I know a few guys who like to do a single session have gone back and forth and I'm a pro tools guy, so this is why I'm wondering the times where I like to mix in a single session, it tend to be when it's a more homogenous sound on the record.

(00:22:38):

If I'm doing a death metal band and there's not much variation between the songs, they don't all have a completely unique arrangement, then it makes a lot of sense to me. You can keep it super consistent and once you get a song mixed well, you're good to go. But when you start to get records where every song has drastically different arrangements, I find that it's a lot harder to work in one session. But I know that a lot of the bands you work with do have drastically different arrangements in every song. So do you have any other suggestions for keeping the pro tools session from getting too crazy besides just print the synths in another session and just bring in the waves? Do you have any other workarounds or is it just trying to get things as consistent as possible, like cleans on a clean track?

Speaker 3 (00:23:27):

Yeah, I think that's every once in a while if there's something with just total different instrumentation and things of that nature, I'll make another session and then work out of there and then balance and import and things of that nature. Particularly with interludes, intros, outros, that type of thing. But yeah, usually it is just things. If one song has a tambourine, I don't create a tambourine track, I just make a percussion track stuff that's processed commonly. You might bust it and run a common bus compressor verb or environment simulation or something of that nature. I might route those. My keyboard tracks, I usually label just key one, key two. I don't go through and label like string what it is. I might label the actual waveform what it is, but I don't create whole new tracks. I think that just keeps everything to a minimum.

(00:24:17):

As far as the CPU usage and things of that nature, I'm really simple. I mean I don't do a lot of processing usually. I try to keep, the sound is pretty stripped down in terms of how many plugins even I'm using. I'm just not a big fan of running 10 things on a snare drum or whatever to get the snare drum. I usually want it to sound like a snare drum, just maybe eqd and compressed a little bit for consistency. So that in and of itself, I guess that fundamental choice to keep the processing to a minimum I think also enables me to use less CPU. So I guess it just depends on how much you're doing in terms of in the specific plugins. We all know like guitar harmonic distortion base plugins or whatever for some reason just use insane amounts of CPU. So maybe bouncing those things out can help sometimes using a sand amp on base or amp farm or something like that, bounce out that stuff so you don't have to actually run it in the session. But

Speaker 2 (00:25:17):

Aside from CPU, what do you think about bouncing it out just for the sake of commitment? Because I've learned that by bouncing the sound down and pretty much getting rid of the source, it's enabled me to get things done. Whereas before I would have analysis paralysis and have way too many options and just never decide,

Speaker 3 (00:25:38):

Oh yeah, like I said, I have OCD to a degree or whatever. And that's one thing I've had to learn to try to let go more so over the years I'm always thinking things could be better and better and the truth of the matter is oftentimes it's true, it can be better, but like you said, you can't get things done. So I think I just as opposed to bouncing stuff out or committing for that reason or whatever, I just, in my brain, I just like, okay, it's good. We'll come back to it. I'll see if it's important later once we get everything done. But I could definitely see that because I'm OCD and it is tough to let go and things of that nature, but I do try to tend to leave things as flexible as possible and not committed as possible. I always keep the direct signals for guitars, for amping. There's always the option for re-sampling drums or changing EQs. Always keep any mini information so in case we need to change the mini sound and just because I know how clients are and I'm really big on trick,

Speaker 2 (00:26:35):

I'll tell you when I talk about this commitment thing, it's true, it's what I do, but at the same time I just do a save as. So I'll do right before I'm about to commit, I'll do save as give it some kind of name where I'm like piano source or a string section source and then save as again the next version of the song, bounce it down, get rid of all the stuff, and then if I need to go back, I can open up that save as session and make a change and stuff, but I try and avoid that the plague

Speaker 3 (00:27:09):

Me also it just how clients are, I mean when they come into the record, they're like, Hey, we want to sound like this. And then by the end of the record, they've changed their mind because the new record come out that they want a copy and emulate and I'm like, dude, that sounds nothing like what we tune the drums for. So there's an element that you have to kind of deal with there. So

(00:27:31):

I'm with you. Like I said, I try to get a really good idea of what the client wants to go for and try to commit to those sounds and try to get them to commit to the sounds and to anybody listening out there just to always save everything. I back up everything in triplicate because I've heard horror stories of people losing stuff or not being able to change tones and things like that. I think you guys have a level of expertise with guitar tones and stuff that I just don't have because a lot of times I'll get a tone. I think it's rocking by itself in the mix or whatever, and then I start mixing. I realize the tone's just got too much gain or not enough, and I generally work with real amps and things of that nature, so I often have to re-amp and things of that.

Speaker 5 (00:28:10):

I'll tell you a secret, none of us actually knows what we're doing.

Speaker 3 (00:28:16):

Sure. It absolutely sounds like your geniuses.

Speaker 5 (00:28:18):

We all think exactly like you do. I mean, I've never cut a guitar tone in my life where I've been like, this is awesome. When I get into the mix, I'm always like, damnit, I screwed this up and I need to fix it. Yeah,

Speaker 4 (00:28:29):

You're not there for the two weeks that I want to blow my brains out and we reamp things for the 25th time.

Speaker 5 (00:28:38):

Okay, we'll just pretend we never had that conversation. Everything we do is perfect.

Speaker 2 (00:28:43):

That's the beautiful thing about all this is that you work so hard on a three minute song, no one hears the 30 days it took to get there. Oh, I know. It seems like a magic trick. Whoa, this song's awesome. You do all this. Well, it took me about 30 days

Speaker 4 (00:28:58):

And I made everyone hate me in the process and my dog won't even talk to me. It

Speaker 5 (00:29:03):

Still sounds terrible to me.

Speaker 4 (00:29:05):

So yeah, I feel like every guy I know that mixes and produces goes through that mental game and at some point they either like what they've got or they have to move on

Speaker 3 (00:29:18):

Because

Speaker 4 (00:29:19):

Someone's going to kill 'em.

Speaker 3 (00:29:20):

I've come to the realization that it's got to be to a certain point or whatever, but some of the best records on are the bestselling records, most successful, some timeless classic records. I mean, there's flaws on them. They're not perfect from the engineering standpoint. Things like not saying that that gives you an excuse to not try to your best to get a killer record or whatever, but holding up a record for a year just because of some tones or takes or something like that is kind of ridiculous when you really look at it in reality. It's just a lot of times things that we hear is not something that the average listener's even going to ever hear or care about. So try to learn to be reasonable about and try to get the clients to be reasonable. Some clients don't care enough about what it sounds like and some clients, they just get too nitpicky about stuff. I'm like, dude, that doesn't matter to anyone and it shouldn't even matter to you. I don't even know why it matters to you

Speaker 5 (00:30:14):

If the snare drum has 0.5 DB of a boost at eight k more, your mom when she listens to the song, isn't going to like it anymore or less either it's a good song or it's not.

Speaker 3 (00:30:26):

Exactly. Yeah, I mean it is a tough thing. There's a lot of psychology goes in with dealing with the clients and it is just dealing with yourself. I think as an engineer, there's a mixed guy or producer, whatever. It's just trying to balance that what it makes sense to really focus on the content, the material at the end of the day, is the song good? Is the take solid? Is the tone solid? Is it perfect? In my answer, in my situation, it's usually never, it's almost never perfect. We got lucky every once in a while and get a killer tone on something or a killer take here and there or whatever. That's just perfect for the part or whatever. But most of the time it's just like, I always feel like it could be better, but I don't know. I have a tough time taking the whole laying approach. Most of my clients don't have that budget to even come close to that. Anyway.

Speaker 4 (00:31:11):

Lang takes it to a ridiculous level.

Speaker 3 (00:31:14):

Yeah, I mean, but that might be what translates into the money. I don't know. But

Speaker 5 (00:31:18):

I think a good lesson for anybody is go dig up, and this exists on the internet with a little bit of Google searching, but you can find stems and things like that from old records. I'll give you an example. I remember one time I was at a bar and I was drunk and I was by one speaker and there was one of the Appetite for Destruction songs from Guns N Roses. I don't remember which one, but it was one of their biggest songs. I was sitting there and I was like, man, the guitar playing on this side sucks. I can't believe there's all these mistakes. And I'm sitting there analyzing it and I mean, I'm totally wasted, but I just couldn't believe how bad the guitar playing was and I never noticed it. And I'm a guitar player, I've listened to those songs a thousand times and I love them and I've never even paid attention to it. So if you want to blow your mind, just dig into some old stems and listen to how amazingly interesting some of the performances are on some of the best songs that have ever been written.

Speaker 3 (00:32:10):

Oh yeah, sweet Child of Mine, Adler goes to the ride on the first hit by accident as a drummer. I noticed that, or Blake actually pointed it out to me from between the Berry Me, it's supposed to be on a high hat, and he hits the crash and goes to the ride once and switches back over. I'm sure you guys have heard of it. Drummers do that and it's in the song. It's like, who missed that? That's insanity. But at the end of the day, does it matter? No, it drives me insane. My OCD, I'm like just, I would've been like, dude, you got to retract that, but apparently they used didn't even care or notice they were probably all high. So

Speaker 4 (00:32:45):

I'm sure that there was some of that involved. So I guess that makes me wonder, what level of edits do you impose on the drums and how much of it do you try to get through the natural performance, and I guess how do you deal with drummers that aren't up to snuff?

Speaker 3 (00:33:02):

Yeah, it completely dependent on the drummer and the production style that the band wants. Usually when I'm working with a band, I tell people, I usually don't like to try to copy any styles or any particular record or whatever, but let me hear some records that you kind of dig the drum sounds on or the overall production, and that'll dictate which way we go about things. If somebody brings in a more produced product that's sample blended or sample replaced or whatever, then I know automatically, hey, a lot of the more modern produced stuff, it's definitely quantized or the drums are straight up programmed. We're definitely going to quantize. So I don't even, while we're tracking, I'm not even concerned about subdivisions and how tight it is to the click or any of that stuff. I'm mainly just listening to the symbols and making sure they're clean and dynamic.

(00:33:44):

But if a band comes in, they're like, Hey, we want to be natural. If they bring in somebody like a mast on record or whatever, or a Curt record that is obviously real, just natural, primarily natural drums, then it's going to be more important during tracking for me to make sure they're close to the click and dynamics are solid and sound and stuff like that. We're going to spend more time tracking. So further than that, it just depends on the drummer. Some drummers come in, they're like, Hey, we want to sound like a Mastodon or something like that, but they're not subdivision solid enough or dynamic enough. Then basically I'll have to take the route of doing more quantizing and sample blending, but I'll try to keep that more natural. I just use the actual kit, the samples from the actual kit and things of that nature and try to just really make it sound as organic as possible. So it is really across the board. It just depends on what the client wants. Honestly, with Blake from between the, he's a monster. We use his real performance takes because he plays dynamically. He subdivisions are solid, quantizing is really, it is there, whatever for sinking reasons and things like that with keys and program material, but it's more loose than I would do say on with some more modern slick metal type production I attempt or whatever, where I would just go hard on the quantizing.

Speaker 4 (00:35:05):

With drummers like Blake, I tend to, well, I've never recorded Blake, but when recording Badass drummers like that, I try to just get the performance out of them and then manually edit anything that needs it. I try to avoid beat Detective in those scenarios as much as possible. Maybe if there's a pattern kick part that needs to be perfect stylistically, then I'll do that because let's face it, nobody can actually play it to the level of perfection that some of those parts need to be at. So on those parts, I'll do it a little bit, but I still, yeah, I know what you mean. I am pretty easy handed about it with a great drummer.

Speaker 3 (00:35:48):

Yeah, it is one of those things, it's like for me personally, I like a record to sound like the band on their very best day, like an idealized version of what the band sounds like, meaning that everything's on time and in tune. Everybody happened to play on stage and just nail everything to the best of their human ability.

Speaker 5 (00:36:05):

I feel like that's a good quote to frame on a wall and put up or something like that. I think that's a really golden nugget. I love it. I think that's a great piece of advice,

Speaker 3 (00:36:16):

But there's a lot of bands who they'll bring in references and they want to sound better than it's humanly possible, and I don't think there's anything bad. There's Fear Factory, they sound like a factory, so they use triggers and everything is quantized, and it's just like there's bands out there who should sound mechanical or with sugar. I mean, they're unbelievable, but you can't have a loose masu. That wouldn't even, to me, that style of music calls for a level of precision to get the idea across that it is probably difficult to achieve in a live court type of situation. So I mean, it just depends on what the client wants and needs to translate what they're doing properly, and it's an opinion at the end of the day,

Speaker 4 (00:36:58):

But in the Fear Factory or Shuga context, that's an artistic choice. That's deliberate.

Speaker 3 (00:37:03):

That's

Speaker 4 (00:37:04):

Not because

Speaker 3 (00:37:05):

They can't do it. They obviously can do it. Yeah, that's my thing. It's like I've had drummers that's just like you said, if the drummer can do it. Sometimes I've had drummers who are fantastic and they want to really produce, and they're bringing me references of like, dude, that's quantized, that's program drums and things of that nature. I'm like, I try to talk like, dude, your drummings awesome. It can sound great, natural. It's try to capture the real performance. To me, rocking Metal has traditionally been a performance based art, and there's a certain energy and emotional connection or something that happens when you're actually capturing and using as much of the performance as possible. But having said that, there's some bands that sound best or some styles of music that sounds best with it, more perfected, periphery. That stuff needs to be super perfect and that's what makes the most impact for that style. So it's just a production call that it's a decision that you make or whatever as you're going along based For me, it's a decision I make based on what they want and what I think is best for their product and record.

Speaker 4 (00:38:10):

So how do you deal with it when you know that they're not capable physically of doing what you want or what they want, but they're hardheaded about how to get there, meaning they want something that's inhuman, but they want to keep it natural, but they're not good enough to keep it natural. How do you approach that without causing World War iii?

Speaker 3 (00:38:32):

Well, I mean, again, it comes back to the way I look at it. Whoever's paying for the record is the boss. If the label is paying for the record and they expect me to deliver a product, I feel like I have a little more leverage with the band. I usually try to side with the band on something, but if they're like, Hey, I want 32nd no kick drums here. I'm like, dude, I know you can't do that. I try I to talk 'em out of it. I mean, I really do. I mean, I don't like doing the whole Dragon Force guitar stuff where you slow the guitars down and speed 'em up. I'm like, dude, it's not going to sound anywhere close to that when you play it live.

Speaker 5 (00:39:02):

Oh, I hate that so much.

Speaker 3 (00:39:04):

Punching in is one thing, but it's just like there's awesome things that you can do with a computer to make something sound cool or whatever, and it is always been done. Even it is done with cowboys from hell, from Panera where they actually recorded a quarter step down and tuned it back up to standard, close to standard production reasons to sharpens transient and things like that. So there's reasons to do stuff or whatever, but I don't mind using the technology to save time and to idealize things to a bit like tuning vocals and things of that nature. But I don't want to tune a person's vocals to a note that they can't possibly ever hit or speed up guitars or kick drums to levels that I just know that this player cannot do literally. I generally try to talk 'em out of it and use reason like, dude, you're going to have to do this on a night to night basis if you become successful possibly. I rarely recommend against that, but at the end of the day, if they're paying, I mean, I have to do what they say. If the label's paying, then I am be like, dude, no.

Speaker 4 (00:40:00):

I'm curious. How do you guys, Joey, how do you deal with artistic disputes between the label and the band?

Speaker 2 (00:40:06):

It's a tough one, man. I usually just try and if I'm sided with the label, then it's pretty easy, but if I'm sided with the band, I will just ignore the label and just, it's not like they're going to fly over here and force me to make the song the way they want it

Speaker 5 (00:40:26):

At the end of the day. I think that requires a certain amount of clout too, to be able to get away with.

Speaker 2 (00:40:32):

Exactly. I couldn't have done that on day one, no way. But if I don't bounce the song out the way that they want me to bounce it out, then who else is going to do it? The other thing is I always have a contract that protects me in that way. There's something called a master, and what that really is, is it's referring to the song. I have Creative Freedom over my masters. So if the label really, really wanted to push something super far to the point where we're just not going to use this, we want want to have this section of the song longer and I'm refusing to do it, they still got to pay me for that song, and then they also have to pay someone else to go remake the song from scratch, which we all know is not really going to happen because let's face it, who wants to go do a whole nother recording session just to make a section of a song longer?

(00:41:18):

So a lot of times I'll win if I really, really feel like it's worth fighting for. However, I do pick and choose my battles, and I know there's sometimes where it's just pointless to even argue over something like that. But between the label and the band is definitely a tough one. And I try to just be on the band side because bands hop around from producer to producer and bands hop around from label to label. You're not really doing a lot by having some kind of alliance with the label. It's better to be friends with the bands. I think.

Speaker 3 (00:41:49):

To me, it's the band's art. Exactly. If the label has legitimate claim about something, to be honest, I've never had a label that cares that much. Of course, I deal with smaller labels than you guys do generally speaking or whatever, but most of the labels are like, cool, 10 tracks enough minutes of audio. Sounds good.

Speaker 2 (00:42:08):

I think the bigger the label, the less, it just depends. It's a different styles of music working with Rise, I'll say Rise is amazing when it comes to Creative Freedom because they sign bands on the basis of like, okay, this is what this band is, we're not going to change it. We're not going to say anything about what they do creatively. And that's kind of how it goes down. I mean, you make the record, it sounds dope, and then you turn it in and they're like, thank you, and that's it. But then there's other labels that like to micromanage everything and

Speaker 5 (00:42:40):

Oh God, I hate that the radio stuff, especially in Rock and Pop is like that. They're very much popular this week on radio. Oh, we need to do that. So whatever you guys have been working on the last three months isn't good enough. Write 10 more songs.

Speaker 4 (00:42:55):

I've dealt with both extremes in big labels and small labels. I think it comes down to the individual personality of the a and r guy and whoever he works with directly over at the label.

Speaker 5 (00:43:08):

I will say this, the most supportive label I've ever worked with. I think one of them on the large scale side was when I did The Fuel by Ramen Atlantic Vinyl Theater and their a and r guy, Steve Robertson was awesome because yeah, he weighed in, he had an opinion and they had some specific arrangement requests, but they let us do pretty much whatever we wanted to do, and it was awesome because the band was very adamant about, this is our sound that we've created over years and this is our team and we want that. We don't want to go to anyone else. This is the kind of record we want to make. And they were really, really supportive of it. And I mean, he even let me master the record, he was like, do you want me to send it to Ted Jensen? I'm like, yeah, that would be cool.

(00:43:49):

I'm like, I already mastered it, but I'd kind of like to hear what Ted is going to do with it. And he was like, oh, I think it sounds great. I'm like, alright, well then keep it. So I was pretty amazed because it was my first major record like that. It is awesome when you have a really supportive a and r guy that you can actually talk to and have a good conversation where it's not like you feel like you're on the defensive as a producer and you have to justify everything you're doing because this track came out by this band on radio four days ago and the record that you're working on now sounds different now. They think it's dated or you know what I mean? I've had some ridiculous situations like that before.

Speaker 4 (00:44:25):

Oh, absolutely. So Jamie, we've got some questions from the audience. I'll just get started with them. So Austin Schaeffer's asking for a band between The Buried and Me. Do you track them to a click and do you have much creative input on their songs?

Speaker 3 (00:44:39):

Yes, I do track them to a Click usually between a Buried and Me, and they're one of the more idealistic bands you could ever work with because they actually track the whole album before they come into the studio themselves. So Blake usually has all his tempos and stuff worked out and click tracks and he just comes in and we just track to what he already has. So basically he's rerecording the drums to get the best possible takes. But yeah, as far as creative input, honestly don't have a lot. There might be a tempo adjustment that I might suggest or harmonies. Usually my input with the Bt Bam is trying is just direct them with tones and that work for layering and harmonies or textures and things like that. They're really, since, I guess the colors record, they've been really into doing a lot of layers and things of that nature, and so that's usually where my input comes in. But as far as the bones of the songs, as far as the drum parts, the bass parts, the guitar parts, I don't really have a lot of input. I used to help Tommy a lot with the vocal harmonies, but he's really coming to his own as a vocalist and he's pretty much writing all his vocals and harmonies at this point.

Speaker 4 (00:45:44):

I think one of the best things you can do as a producer is understand when it's better to just get out of the way.

Speaker 3 (00:45:50):

Some bands, I really try to help give structure ideas and things like that, but with what Between The Bar Enemy does it's extreme progressive type material, there's no rules what I'm saying. There's no like, Hey, you got to hit with the hook within the first 30 seconds and all that you do with a commercial single. I honestly don't work with a lot of those type of clients, so unless what they're doing just sounds bad or not good, then I am really big on, let me hear what you're doing as we go. A lot of times, most of the clients I work with, they don't do any pre-production sessions or anything like that they did back in the most. Clients honestly don't even send demos even though I request them. So a lot of times I'm hearing a song for the first time while they're tracking it, so I just let 'em record it and put it down how they have it, and then we'll go back and make modifications and tweaks at the end or whatever. If I feel like there's something that can be improved. And luckily as I've gotten on in the years and I've been doing this for a while, more people are more open to my ideas and early on I would just try to recommend stuff and they'd be like, no.

Speaker 4 (00:46:53):

Yeah, it takes a while before I think someone's built up their name enough to where people just inherently trust them.

Speaker 3 (00:47:01):

I think those beginners out there, it's like, so don't get discouraged if you know you're right about something.

Speaker 5 (00:47:06):

Sometimes the band has to fail on their own and learn from that mistake. So if you show people the result, sometimes they will resent you, but if you help them figure it out, they'll respect you for it. So you got to be careful with psychology, but sometimes they just have to fail. It is what it is.

Speaker 3 (00:47:23):

A lot of psychology goes in this. It really is. I mean, as far as getting along with the band or the artist and helping the band get along with each other and helping the band get along with the label. Going back to what we were saying with the labels, I always encourage the band to keep the label happy and especially early in their relationship, the label can do a lot for them if they decide to oftentimes, and the bands just usually are just, I hate the label. They're not giving us any royalties, which is true, but it's just like, dude, you still want them on your side. You want them to make that phone call or sign that check for the tour support or whatever. So it's just at least entertain what they're saying. Anything that you can stomach of their ideas, try to entertain it. Ultimately a big cog in the business as far as making a living, playing music and the more successful the band is, the better for us as engineers, of course, that's what drives Ark business, and so I try to help the bands material wise or whatever, try to make recommendations that might help them be more successful as far as its tone wise that might make them more successful as far as interactions with each other and the labels that might make them more successful. I try to make recommendations where I think I have some insight.

Speaker 4 (00:48:42):

Yeah, I think that's really, really important. So AJ Vienna is asking, when tracking drums, how do you handle the micing and recording process? And also with bands like Bt Bam and Scale, the Summit and Wretched, did you try to track them dry and then sample rooms, or do you throw up room mics?

Speaker 3 (00:49:02):

I usually throw up room mics. I mean, usually a lot of the projects I do, I do out of my basement here, and it's a small room, and so there's not a lot of room, natural room ambient. So almost always supplement with some sort of convolution reverb to emulate a large space. But with a last, between the bearing me, we recorded a nice studio and so we actually had a nice room to actually mic up and capture the sound. But yeah, I always record the room mic. So yeah, I'll mic each individual drum. The kick, I'll use a mic, two or three mics and the snare, two or three mics and each Tom and the symbols that usually either, depending on their symbol setup, I usually try to at least capture stereo pair of symbols, the hat and the ride and stereo room and a mono far room usually.

Speaker 4 (00:49:45):

Just to go a little deeper into what you said, what are some of your favorite snare mics and miking techniques? You said you use three or four and I also use three or four, but I also know some guys that just bottom and top. So I'm curious, what are some of your go-tos on snare?

Speaker 3 (00:50:02):

Yeah, that's kind of a recent thing. I mean, usually it's just top and bottom for sure, but every once in a while I'll add a side mic. I've seen that and actually laughed when I saw that. I'm like, why is he Mike in the side? But I was like, I'm going to just experiment with that and it is particularly useful in terms of when you have to really hard gate the snare. And I usually have a challenge of getting the symbols out of the snare if we're trying to use a real snare sound and just to add a little bit of body back to the snare drum without a bunch of symbols in it. It's kind of a strangely useful thing.

Speaker 4 (00:50:39):

I've actually done that same thing and I've also found that saturating the side mic sometimes can be really, really cool.

Speaker 3 (00:50:47):

Yeah, compressing it hard and doing weird stuff that you can't really do with the top mic because of the hat bleeding things. I've got these little, I can't remember what they're called, but there's just covers to help reduce symbol bleed, but if you put it on the side mic or whatever, it really, you get a pretty clean snare body sound or whatever's kind of an interesting thing. And every once in a while I'll kind of put a condenser in the room, kind of more aim just to capture the snare.

Speaker 4 (00:51:11):

We were actually talking about that yesterday on the podcast. One thing I like to do, it's not a condenser, but hang an SM seven B right over the snare, pointed right down, but above the overheads. It just, it's a really cool trick.

Speaker 3 (00:51:25):

Yeah, I'd like to try that. Yeah, like I said, I've seen people do crazy things and oftentimes it's just I start with the basics and see what we have. If I'm satisfied that it just depends on the snare drum, the player, and obviously, like I said, if you're going to more sample blend or sample replace route, then doing a bunch of that stuff is unnecessary. I want to see if the player's good first. He's just playing raw with dynamics and stuff like that. I'm just like, I'm going to have to do sample blend or replacement anyway, so it's like I'm not going to put a bunch of mics and things of that nature.

Speaker 4 (00:51:59):

I've definitely got my limits with that too, because I like to go crazy with Micing and spend a long time on tuning and getting shit just perfect. But there's times where you do all that work and that it's tuned. I work with a great drum tech because I don't trust the drummers to tune well and I know when stuff is right and then you get the drummer on there and no matter what you do, it just doesn't sound that great. And so I've kind of learned to understand those situations

Speaker 1 (00:52:31):

That

Speaker 4 (00:52:31):

I'm not going to settle for something bad, but I know that the majority of the sound is going to come from the samples and so I won't take all the time in the world. I mean, I'm not going to have out tune drums or anything dumb happening. So what about Tom's? You said you like to throw on more than one mic?

Speaker 3 (00:52:52):

Well, generally I don't, yeah, I don't do the whole top and bottom thing. Normally I'll just use one on top or whatever the Tom's or whatever.

Speaker 4 (00:52:58):

Oh, okay. Lots of guys don't seem to bottom Tom's mics.

Speaker 3 (00:53:02):

I've done a few mixes where people have done and I haven't found 'em really, I guess not necessarily that they're not useful, but they're just not necessary for the Tom sound that I usually go for, I guess. So I guess that's just it. I mean I just haven't found a way or need to use it. To me, a snare is a really important part of the sound. A lot of times the Toms are just kind of, I've had bands I'd spend hours micing up their Toms and they hardly use 'em on the whole record it like I've had people come in with these monster kits and double base and not even touch the other kick. It's just like, okay.

Speaker 4 (00:53:39):

I always make a point of addressing the structure of the kit before we get going. Unless it's like a dude from a super old school band who's been playing the same enormous setup for 30 years and there is no way that he's going to reduce it to three times. No way. It's not happening no matter what you say. So don't even bring it up. So something that Giovanni Angel is asking is what was the toughest situation ever for you in a tracking session?

Speaker 3 (00:54:10):

I think mainly there's a few clients that I've ever worked with before that are just assholes, honestly, just totally uncool people and I hate that. I would rather work with a cool dude that's not a good player than work with an excellent player that's just a total asshole or whatever. It's tough for me. I've developed an anxiety disorder, a people pleaser. I want to try to make everybody happy by nature. I know that's difficult and a lot of cases impossible, but with some people it is just really impossible. It's just definitely the people they come in, they're like, yeah, I'm not really feeling that and blah blah. I'm like, dude, we not even, it's not mixed. It's you like you told me yourself, you've never recorded before in a real studio and then you're trying to tell me how to do my job.

Speaker 5 (00:55:03):

Armchair mixers. Oh God, I hate.

Speaker 3 (00:55:07):

So I'm not going to point out any specific people or projects or whatever, but I've had that happen and it just, it's horrible. I mean, it causes damage to my soul for some reason. I wish I didn't let it do that, but it just really hurts when somebody is just an unbridled asshole for no reason.

Speaker 4 (00:55:27):

Yeah, I concur on that. So here's another thing that Giovanni Angel is asking is in the bands that you've worked with, do you see more digital amps or tube amps? And especially these days, what are you seeing more of?

Speaker 3 (00:55:44):

Oh yeah, of course these days they're like, oh sweet, you got an ax effects. Let's use that. And that's a big thing with the younger generation, but I've also got a stack of heads and the older generation, older guys come in, they will not plug into the X effects. So

Speaker 5 (00:56:00):

I hear that.

Speaker 3 (00:56:01):

Yeah, it's split between the two camps. Yeah. But I've definitely seen a lot. To me, you can get great sounds with the pod. You've got Joey's tone forged down and you've, there's a lot of plugins that can sound fantastic and obviously the Kemper units, NAX effects can sound great if you tweak 'em. But I also love the sound of real amps. If you've got a really amp with some good tubes in it and great sounding cabinet and things like that, there's some magic that happens there. And it depends on the project. I think with the plugins and with the amp emulators and profilers and things, for some reason you get a little more definition easier I guess with those amps. It is tougher to get that kind of definition and articulation and percussive quality out of a real amp that you get with those things. And sometimes you need that percussive sound or whatever that definition for the style of music that the band is a really modern articulate, alternate riff type stuff. You guys know what I'm talking about? I'm sure listening's probably too.

Speaker 2 (00:57:08):

Yeah, it's the air.

Speaker 3 (00:57:10):

Yeah. But then like I said, you get more of a rock band or whatever, something just seems more large to me with the real amp deal. I don't know, maybe it's just an old school or whatever. But

Speaker 4 (00:57:20):

No, I think there's definitely a place for both. I think you can get great or terrible results out of either. Yeah. Takes

Speaker 5 (00:57:26):

A lot more skill to mic and amp though than it does to dial in a patch preset in my opinion. So it's easier to mess up. There's a bigger learning curve I guess is my point with there's

Speaker 2 (00:57:36):

More variables too,

Speaker 3 (00:57:37):

Just moving the mic a fraction of an inch or whatever on the speaker cab means everything. It's just crazy stuff like that. But I mean I think it takes a lot of skill to get a real amp or a plugin to sound great too, because you have to have the ear and you have to know what frequencies are there that are weird and things of that nature. And I don't know, there's challenges to both realms and there's a skill to be developed both ways. And I think I try to just do both whatever the clients feel comfortable with, whatever the production style kind of calls for that kind of thing or whatever. So I don't think there's any right or wrong there.

Speaker 4 (00:58:14):

I think the most important thing to just understand going in is that you have to approach them differently. Just like we were talking earlier about EQing in the box or out of the box, it's different. It'll do different things

Speaker 3 (00:58:27):

Absolutely.

Speaker 4 (00:58:27):

Because just different and Amps versus Sims, you can get great results out of both, but you shouldn't approach them the same way because even though you're using an IR and a microphone emulation, it's not going to behave the way that a cabinet and a microphone behave. It's just not, it's a whole different thing. So just approach it differently. Approach it like you're learning a brand new skillset. So Greg Hink is asking, I'd love to hear about some of the vocal processing and clean guitar tones on the latest contortionist album.

Speaker 3 (00:59:01):

I'm trying to remember.

Speaker 4 (00:59:02):

Talented band. I've worked with them too. Very talented. Yeah,

Speaker 3 (00:59:06):

It's got a lot to do with them just being awesome as far as players and things like that. But strangely enough, I think we used the Mesa Boogie Mark five for all their tones. I think even the clean, we just kind of switched the channel like, Hey, sounds great. And they got some ivanez or whatever from Ivanez that had coil taps or whatever. I think all the clean tones or most of 'em had, we used a split coil just pass the pickups or whatever came in their ivanez and we actually just ran 'em through an old school boss me 50 multi effects pedal.

Speaker 4 (00:59:36):

Those are good

Speaker 3 (00:59:38):

Dude. Like I said, I used to have all the separate boss pedals and all these pedals and then a kid came in with one and I sit down an ab beat. I'm like, this sound exactly like the pedals. Why do I have a whole shelf of pedals when I could just get this? So I just sold the pedals and got that. Most people would want, pedals usually have some cool stuff when they come in the studio that they want to use, but they didn't because I think they have ax effects as they use live or something like that. Or they did at the time and they were just wanted to kind of try to use a real amp and they just say, Hey, that Meis looks cool. And I think we plugged in the Mesa and the JVM, the Marshall and I've got an old PV Ultra and we just tried some different combinations and they just ended up liking the Boogie.

(01:00:17):

They just wanted to kind of, I guess a more organic sound or whatever for the new More Rock or something less mely and that the Boogie just has that big fatter sound I guess that they were kind wanting to go for on the record. So that's all we did for cleans, honestly. It's just mess around with that pedal with some occasional chorus and reverb and the Mark V into a Mesa cab standard with Vintage 30 with an SM 57 in the middle somewhere. And then vocals, we use my Norman U 87 into my Vintech or whatever, which is like a Neve clone.

Speaker 5 (01:00:50):

I love an 87 into a Neve. That's a great combination. One of my absolute favorites.

Speaker 4 (01:00:55):

Hey, that's the exact same chain I used on that guy as well.

Speaker 3 (01:00:59):

Yeah, I mean it just seemed to work with his, I tried, I got an SM seven and I got a couple other Mikes that I trial all people and that would just seem like the good combination for Mike's voice or whatever. So we just went with that. As far as effects and stuff, we did all kinds of stuff. I mean it was just basic compression overall. Mike's just a fantastic vocalist, so tuning his vocals was minimal.

Speaker 4 (01:01:20):

Yeah, I think that people need to understand something really, until you've worked with a great vocalist, you may not get it, but he sounds great without any of the fancy stuff. You can get him sounding almost album ready straight in. That's when I got his voice coming through. It was like, okay, this is phenomenal. So from that point on, it was just how do we want to dress this up? And I'm sure it was a similar thing for you. A lot of guys haven't had the opportunity to work with someone that good, so they're thinking more in terms of what do you do to get that magical sound. But it's him, he's great.

Speaker 3 (01:02:02):

And unfortunately that's rare in this style of music in particular have somebody who can sing and pitch and who has a great tone and great feel naturally. But yeah, so I mean literally just put some different verbs on him here and there and some echo and delay. And we had some cool fun vocoder moments where we'd actually build vocoder sounds with him actually singing the seconds and things of that nature. And we mess with some little toy megaphones and just fun stuff like that. Just little tone modifier type stuff or whatever. I think I have a couple vocal pedals, like a TCL electronics thing that does some vocoder robot sounds and just so we messed around with a lot of ideas like that

Speaker 4 (01:02:41):

Sounds about right to me. Something that Dmitri Jablonsky is asking, please share some techniques you would use to track and mix bass to achieve the huge bass sound, but still make it really stand out in the mix.

Speaker 3 (01:02:55):

I'm probably not the best guy to ask us. You guys would probably get bigger bass sounds than I do, but generally what I do, I'm still a big fan of the actual bass amp sound or whatever. I just feel like it kind of blends in the mix a little more organically. Like you get with direct bass or whatever you get, you get the extended low wind. It just doesn't happen with a real amp in the mix. I dunno, it's kind of a preference thing there or whatever. But normally I'll just mic up the amp peg or whatever the bass player uses. I usually mic a beta 52 off axis on one of the speakers and then blend it with a Sennheiser 4 21 on axis and usually blend those pretty evenly on the cab itself. And then in the mix, oftentimes if somebody wants, I oftentimes do parallel processing where this is a pretty common thing where somebody will maybe cut almost like a crossover type situation where you'll cut the lows on one track and run some drive or distortion on one of the tracks. And then the other track you preserve more of a full frequency sound or just the lows only you can compress and mix those differently separately. Very similar technique what other people do. And if you wanted to extend a low end, like I said, you could always add in the direct signal. Any guitar is a bass. I record, I always record direct signals as most people do.

Speaker 4 (01:04:09):

I don't understand why people don't, sometimes it's no extra effort. I mean other than setting up another channel, do it.

Speaker 3 (01:04:17):

Yeah, it drives me insane when I get something to mix and there's no DI's just for potential quantizing needs just even if you just use it to see the rhythms to make sure everything's kind tight or whatever. Every once in a while you need something you need to tighten up and all you have is the distorted track or whatever. You can't do it. It's just like you're guessing. It's just yeah, absolutely. Everybody just track direct guitars, please.

Speaker 5 (01:04:40):

We will find you and hunt you down. Yeah, there's

Speaker 4 (01:04:43):

A law I wish there was. Well, the thing that bums me out is when you get something to mix and a guy is like, I want my, and I'm not talking about Eddie Van Halen hitting us up or something. I'm talking about some guy who's just real personal about some angle amp he's had for 17 years or something and the tone that they send you kind of sucks and there's no DI's, and it just kind of worked you into a corner where even if the tone he sent you was good, it would still be helpful to have the, because at least you could edit it or fix it or blend it with something who knows. Absolutely. A bunch of reasons to have a di even if you're going to use the tone that's given to you.

Speaker 3 (01:05:28):

Yeah, like I said, I mean there's been countless times where I got a tone. I think it's sounding awesome even in initial tracking, but you start layering up stuff and you realize it's just too thick or too much distortion or even not enough, it's too weak or whatever and you have to go back and reamp it. And it is just a safety net thing for me and it's useful for quantizing purposes if needed. And like you just said, there's no reason to not do it. Not that difficult. Just use the track.

Speaker 4 (01:05:56):

Totally. Dude, that's all our questions from the crowd and that's what we got, man. I want to really thank you for coming on. It's been great talking to you and we love your work.

Speaker 5 (01:06:06):

Yeah, Jamie, you've been awesome. Thank you,

Speaker 3 (01:06:08):

Man. You guys are, like I said, you're the masters, so I watch your classes and things on Creative Live myself and I'm trying to steal all your sounds and techniques.

Speaker 4 (01:06:18):

Oh, and let me just say that people listening, you should also check out Jamie's Creative Live. You did it between the Buried and Me and it was all about how you guys worked together and the most recent record, right?

Speaker 3 (01:06:32):

Yeah, yeah. Well it was actually Tommy from between the in his solo record.

Speaker 4 (01:06:37):

Oh, okay. Sorry.

Speaker 3 (01:06:38):

But yeah, so we just went over some of the things we did for that record and yeah, we covered some pretty interesting stuff in there Might be some useful information. Yeah,

Speaker 4 (01:06:47):

I thought it was a really cool creative live for sure. So well

Speaker 5 (01:06:50):

You go check that out audience if you're listening.

Speaker 4 (01:06:52):

Yeah, definitely. Go check that one out. So. Alright, man, well thank you very much

Speaker 3 (01:06:56):

And thank you guys so much.

Speaker 4 (01:06:58):

Really appreciate it.

Speaker 3 (01:06:59):

Thank you guys so much. And yeah, I'll talk guys later.

Speaker 1 (01:07:03):

The Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast brought to you by Mick d Fs p Professional audio plugins. For over 15 years, Mick DSP has continued producing industry acclaimed and award-winning software titles. Visit mc dsp.com for more information. The podcast is also brought to you by Slate Digital. All the pro plugins one low monthly price. Visit slate digital.com for more information. Thank you for listening to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast. To ask us questions, make suggestions and interact, visit urm.academy/podcast and subscribe today.