BEAU BURCHELL: Mix Translation, Printing Stems Correctly, The Story of the Saosin CLA Mix

Finn McKenty

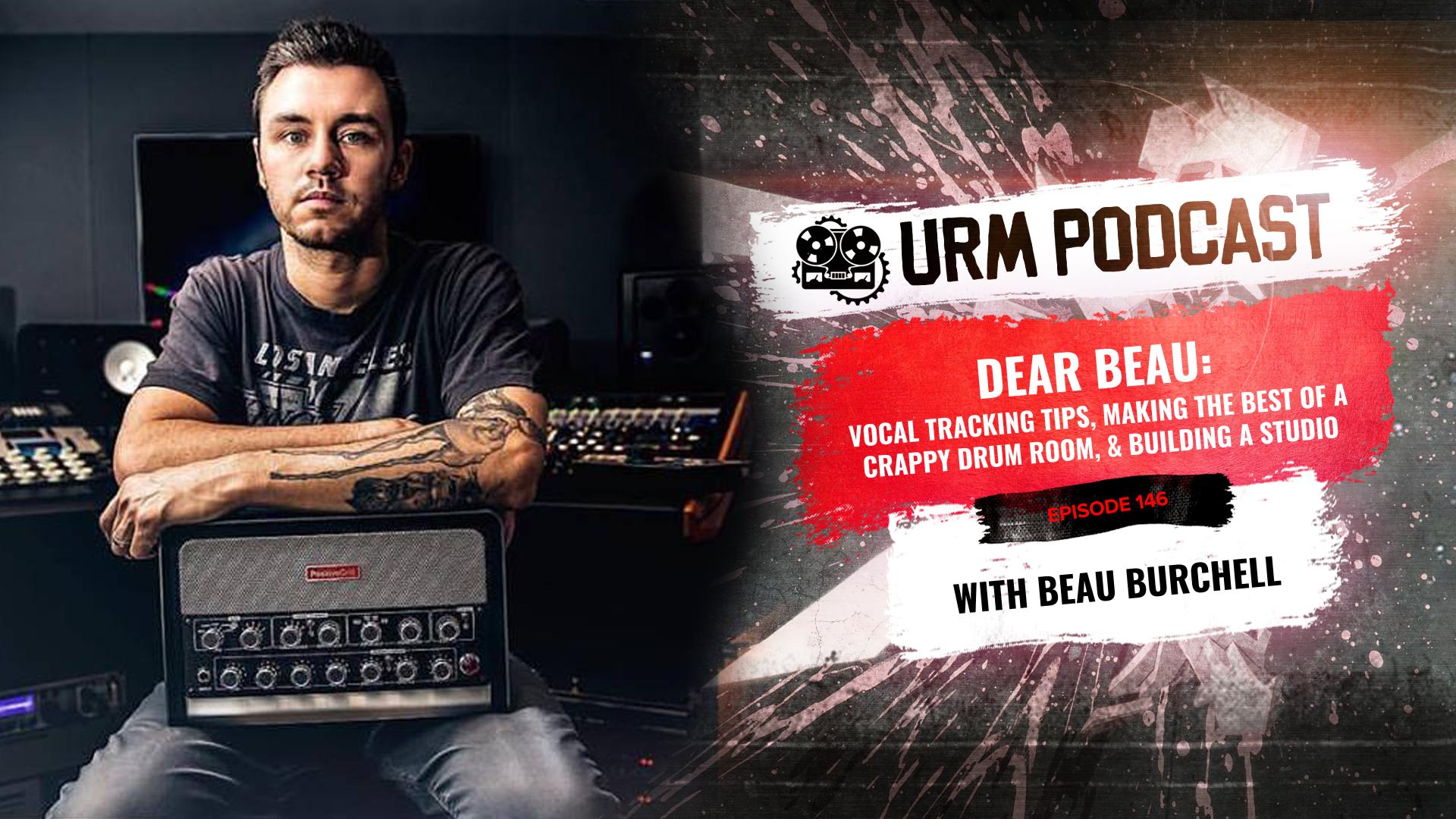

Beau Burchell is a producer, mixer, and guitarist best known for his work with the influential post-hardcore band Saosin. Operating out of his Los Angeles studio, he has produced and mixed for a wide range of artists including Senses Fail, The Bronx, Hundred Sons, and Middle Class Rut. Known for his meticulous approach to tones and modern production workflows, he brings a ton of real-world experience from both sides of the glass.

In This Episode

In this “Dear Beau” Q&A session, Beau Burchell hangs out and answers a ton of your production questions. He gets into some seriously practical gear and workflow talk, breaking down how he uses the Kahayan amp switcher and his go-to Axe-FX bass preset. Beau shares crucial advice on printing stems—including why you need to commit your two-bus processing—and explains how high-end converters can sometimes mess with your mix translation. He also tells the story of getting the self-titled Saosin record mixed by Chris Lord-Alge and offers a ton of pro tips for real-world scenarios, like recording drums in a crappy room, building a studio from the ground up, and checking your mixes for harshness and phase issues. It’s a super chill but info-packed episode full of actionable advice for dialing in your own process.

Products Mentioned

- Kahayan Amp Switcher

- Fractal Audio Axe-FX

- Tech 21 SansAmp

- Apogee Duet

- Apogee Symphony I/O

- Apogee Big Ben Master Clock

- Lynx Hilo

- Antelope Audio Interfaces

- Universal Audio Interfaces

- Waves LoAir

- Waves Renaissance Bass

Timestamps

- [0:05:50] How the Kahayan switcher improved his amp tracking workflow

- [0:11:24] Breaking down his Axe-FX distorted bass tone

- [0:15:50] The right way to print stems with two-bus processing

- [0:18:01] A horror story about a mastering engineer and incorrectly printed stems

- [0:23:02] Why high-end converters can sometimes make mix translation harder

- [0:28:07] The story of having Chris Lord-Alge mix the Saosin record

- [0:35:47] Tips for recording drums in a less-than-ideal room

- [0:39:55] Using a sine wave generator to learn a new control room’s peaks and nulls

- [0:45:22] The challenges of designing and building his own studio

- [0:58:48] Getting big, low-gain guitar tones using Axe-FX and input filtering

- [1:03:22] Beau’s vocal tracking and comping process

- [1:09:21] Deciding which tracks to use when mixing a session from another producer

- [1:11:15] Why he often doesn’t use the kick out (NS10) or mono room mic

- [1:15:56] The difference between making music and being in a band

- [1:18:43] Using the mono phase-flip trick to check your side information

- [1:22:47] Using a massive high-shelf boost to check for harshness

- [1:25:34] How to check your sub-bass content without a subwoofer

- [1:27:54] Advice for live sound engineers trying to land a good touring gig

Transcript

Speaker 1 (00:00:00):

Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast, brought to you by Drum Forge. Drum Forge is a forward-thinking developer of audio tools and software for musicians and producers alike. Founded on the idea that great drum sounds should be obtainable for everyone, we focus on your originality, drum forge, it's your sound. And now your host,

Speaker 2 (00:00:20):

Beau Burchell. Welcome. Welcome back to the URM podcast, Beau Burchell here doing another Dear Beau episode, thank you so much for writing in and asking me questions. I love, love, love talking about audio dork stuff. So this is super fun for me. Dear Beau, episode number two, pretty cool. We have a crap load of questions, so I'm going to try to not have too much diarrhea mouth and try to keep this episode under, I don't know, maybe an hour and a half maybe. That would be nice, right? Although I would like to say I had a pretty great day today. You guys that are mixing records and having things be released, whether it's on Facebook or band camp or wherever they're being released or on iTunes, whatever, it's always a really cool it feeling when all of the work that you and the band and everyone put into making a record and then that record finally comes out.

(00:01:22):

And I guess it's always nice when it gets a positive response from people. So I had that happen today. There's this band called Hundred Sons that I mixed a record for and the single came out today and it's doing pretty well. Everyone's psyched on it, and I'm especially happy with it because for me, that's, if you listen to that, the song's called Last Apology, and if you listen to it, it's got a fairly, what I would call kind of a high to mid tuned snare drum. And it's not normally something that I gravitate towards. I normally am drawn towards kind like a beefier snare or a medium tuned snare, but that I feel like is kind of a little more of a high kind deftones type snare. And whenever you're working with stuff that's a little outside your comfort zone, it's always just, I get a little bit nervous. You don't have that comfort of knowing like, oh yeah, this is where my snares would punch and it feels great. So anyways, that came out today and it, it's really nice that people are enjoying it.

(00:02:31):

Also, I'm working on this census fail record right now, and that's just going fantastic. And then I just finished mixing another middle class rut song, and the reason why I'm bringing this up is because there's that speed mixing course that URM is doing, and I read some of the outlines and was having one of those aha moment, oh yeah, I forgot about that. Oh yeah, I should really try to focus on that tonight. So anyways, it was kind of cool. I set a stopwatch on how long it took me to mix this song. Granted middle class rut, if you haven't heard them, they're a very simple band and they have, it's just drums and guitars. There's no bass, which also presents a little bit of a problem because you don't have that constant sub low end, so you have to figure out ways of making it happen.

(00:03:23):

So anyways, but yeah, so I time myself tonight and even though I wasn't supposed to really do prep work and mix at the same time, I just said Screw it and went for it. So I mixed prepped the song. It took me 20 minutes to mix prep the song, and then it took me 30 minutes to mix the song. I sent it off and the only note I got back was potentially doubling the chorus, which means basically I killed the mix first round, which is always a great feeling also. So anyways, all in all, I'm having a pretty awesome day today, so I'm pumped.

(00:04:02):

One other thing I'd like to mention, because when you're talking to friends about this stuff, it's always just kind of cool bringing up stuff. So for instance, today, how easy it was for me to mix that song, I have another friend, and earlier today we were FaceTiming and he was just kind of having issues mixing a track that he had produced. And one of the hardest things about mixing a track that you've produced is you already know what went into it. So he was having a problem with the kick drum and the snare and basically just everything that involves mixing because he knew that he had already added, let's just say five DB at say six K on the snare drum when he was mixing it, I told him right away, I was like, man, I think the snare is kind of dark. I think it can kind of pop a little more.

(00:04:58):

It's darker than your usual snare. And his reply was, well, I'm already adding three DB to it. And if that was anyone else's tracks that you would get, you wouldn't care how much you were adding to it. You would just say, man, this snare is dark as crap. I got to add 20 db to this thing. So yeah, it was just one of those things where we both kind of sat there and we were like, dude, I think you're really fallen victim of trying to mix your own stuff and you're just, you've set rules on yourself that shouldn't be there. Anyways, I just thought that was kind interesting. And just a little fun tip to share with you guys that when you are mixing other people's tracks, you kind of have an advantage because you don't know what they did going into it, but at the same time you kind of do want to know what was going into it in case they're asking you to preserve some of the character.

(00:05:50):

Anyways, ramble over. Let's jump into it. First question, Michael Bivens. Hey Beau, thanks for doing another podcast. Could you talk a little bit about how the Kaha switcher has improved your workflow? What were you doing before during tracking and how has that changed? I'm designing an AMP rack with all my heads and a Creactive load box, and I think it would make a great centerpiece. Thanks and have a good one, Mike. Well, Mike, I mean, I'm going to sound a little bit like a high-end audio switcher sales rep right now, but this thing is awesome. So I have, lemme just move a little bit. So I'm looking at it right now and what I've got going is, the way it works is it's almost like the internet or a cell phone for your, it's like one of those at t commercials connecting the world, but it really is.

(00:06:49):

So before I used to, I had a patch bay that I made. It was all quarter inch connectors that would all of the output, the speaker outputs of my heads would all go to a female quarter inch jack on a single space rack panel that I had made. And then, so there was eight female quarter inch panels to connect the speaker outputs. And then I had four female speaker outputs that would then tie into my ISO booth to where I could have four cabinets set up there. So what I would have to do is I would have all of my heads on, but on standby and then whatever head I wanted to use, I would have to, because I always take a di whenever I'm tracking, in addition to whether it be ax effects or AMP or whatever it is I'm tracking with, I always take an extra clean di.

(00:07:40):

So I would have to go out of my DI box out, I guess the through DI box then into whatever head I was using. So I would have to patch the guitar into that head, and then I would have to patch the speaker output into whatever cab I was doing and then turn the cab off of standby because when you're using the quarter inch cables panel, which now looking back, I should have been using something like a speak on connector to where the two, I guess it would be positive and ground where they never actually can cause a short, but because just the way the mechanics of a quarter inch cable work is when you insert it, there is a certain point in there where the sleeve, it's like the tip and the sleeve are both touching or they connect and cause a short for a split second.

(00:08:29):

So anyways, so that's what I would have to do. Now with this, everything's plugged in. All of the inputs to the guitar heads are plugged in, all the outputs, the speaker outputs are all routed back into this box. All of the two, the speaker cabinets are routed to this box and it's all just push buttons right on the front and whatever head is not being used doesn't receive signal from the guitar. Therefore, the amount of load that the load B or the phantom load or whatever it's called inside of this unit, it's a very small load because the head is just idling. So it's amazing. So imagine if you had four different amp sims on your track and you just bypass them all and then you just wanted to, okay, how does preset one sound boom, how does preset two sound, boom, boom, boom, boom, and it's that fast.

(00:09:26):

I can actually go through this setup faster than a plug than different plugins because if you really get down to clicks, I just click amp number one and then I click AMP number two. Whereas on a plugin, unless it was all within the same plugin, I would have to deactivate one, then reactivate the other. So it's actually one click faster than even doing it in plugins. And then on top of that, now I have the micro robot in there, which I think I'm going to get another micro robot for my second cab. So I like to have one cab with vintage thirties and one cab with greenbacks in there, and then I can choose depending on the part. Anyways, yeah, so far I've only been using it on the census fail record, but so far it's just been awesome, especially when you really compare an amp with zero.

(00:10:18):

It's as fast as changing a channel on your amp. It's that fast. So where you don't have that five seconds of patching in a different amp and then your ears adjust and you can't tell the difference, it's literally boom, boom, ab, you're done. So you can flip through. I've got 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 amps all on right now and just ready to go and I just plug it in done. So yeah, it's been awesome. So if you are thinking about building one, I would definitely say go for it. And if you want to send one my way, then I would love that. Yeah, thanks Mike. Next question, dj. Hey dude, I just finished listening to your episode and really enjoyed Hope It's the first of many. Yeah, man, me too. Apologies if you've answered this before as I haven't checked out the live mix video. But if not, could you elaborate a little bit in terms of the amp or distorted bass tone on the silver string track?

(00:11:24):

I really liked it. Yeah, I cover this in the live mix, so you should watch it. But basically what it is, is I feel like everything we do now is just stolen from periphery. And when I say we, I mean the collective audio community. I mean they're just so good. But anyways, yeah, essentially it was for a while on the ax exchange of the ax effects, there was a nly bass setting that he had done. And I think in his setting it starts with, so the guitar di goes in, and if you're familiar with ax effects, you'll kind of understand the blocks. And hopefully if you're not, then I won't sound like I'm talking about rocket science right now, but anyways, the way it works is you have this grid and there's blocks. So the way it works is it goes in your clean, DI comes in, and then that gets split to two different blocks.

(00:12:25):

Then let's just call your top row of blocks is going to be like our base or sub channel. And what does that get? I think there was a compressor on it, and then it goes straight to the base head and then I forget the rest of his. And then the other amp that gets split down to the second row was a filter that kind of chops out all the bottom end. So it's not making that flubby sound that you would get whenever you track a bass through a guitar head. And then from there it goes to a Marshall style head into a Marshall style cabinet with a 57 or whatever he was using to mic it. And then those get combined at the end, and I think he was even doing some extra multi-band EQ or multi-band compression inside of the ax effects. But I just decided to kind of dumb that down and give myself something that I felt would work almost everywhere.

(00:13:27):

I can use this kind of setting. Now that I have on, I've used it on, let's see, there's this ages record called weightless, and they spent a lot of time getting their base tone, and then I asked the band if I could do an AB with this tone that I had here, and unanimously everyone in the band chose this X effects preset without it. I was like, oh my God, that's got to be the real amp. It sounds insane ed, but nope, it was my X effects Anyway. So what I've got is DI comes in, signal gets split, the top row is just the, it's like the AD 200, it's like the orange sim, and then that goes to a four by 12 cabinet micd with a, and it's like the Yamaha Subick speaker, and then that goes out to output one, which is like your left channel.

(00:14:27):

And then now going all the way back to block one, it gets split down to row two, and then first block is going to be a high pass filter, and that'll lop off some of those bottom end so it doesn't make your Marshall style head all farty. Then I've got the Friedman brown eye on there going into a marshal, and that comes out channel two. So ultimately what I've done is a similar thing to what a lot of the guys are doing where they take the clean sub track and then duplicate that and only put a San Z or distortion on the mids and high mid and high end of the base. So I've kind of done a thing like that, I guess in its simplest terms. So if you have an X effects, you can experiment with doing something like that. But I just love the way that the subick mike sounds. It is just really full and a little more harmonically rich than just using a clean DI bottom end.

(00:15:39):

Elon, is it Elon? Elon Benita. Man, I feel like we have so much interaction and I'm always buting your name, hopefully that's right. Elon Benita. Hey, Beau, one question about routing. You said you have an easy way about printing all your stems at once with your routing. Could you expand on that? I may have either used poor English or not known exactly what I was saying if I did say that because I can't print them all at once. Basically, it makes it very easy when I do my stems because now if you've seen my template for my bus, my busing system that I have, so what I do is all of my drums are always going to my drum bus. All my bass is going into my bass bus guitars to guitars programming to programming vocals to vocals, and then all the band elements go to a band bus.

(00:16:38):

So what it does is as soon as I want to print my instrumental mix, I just mute my vocal bus. As soon as I want to do my drum stem mix, I just mute everything except for the drum mix. So unfortunately it's not a fast way of doing it, it's just a really nice way of knowing that if you've routed everything correctly in your setup, when it comes time to do your printing, your stems, it's a very easy systematic way of just going down the line from top to bottom on my busing. Okay, first up, drum stem, done print that in, and then that gets printed down below in the session returning from my two bus outboard compression. So for me, I have a two bus compressor and EQ that goes on my entire band mix. So what I would do, and I'm using that as a hardware insert, so what I would do is I would just create a new track called drum stem, bass stem. The input of that track would be the return of my two bus compressor and eq. Hopefully that makes sense to you guys.

(00:17:50):

That's how I do it, and it's very nice, and I would say it's very important that if you do have any two bus stuff going on on your two bus, you need to make sure that that stuff is there when you print your stems. Because I did run into a problem of this where I printed my stems for a record and then a mastering guy that I've never used before, and it was, I guess the label wanted to use them or something, and this mastering guy just tore me apart and made me look like an idiot in front of the label. What his argument was is that he went to the label saying that in order to master the stems, first off, I don't even know why they wanted to master the stems, that just sounded stupid to me. But regardless, they wanted to master the stems and he was going to charge them an entirely new mastering fee to master the stems.

(00:19:00):

And his reasoning was is that the stems when combined don't sound like the mix that I had him master. So therefore he can't just throw his settings on my stems and master them. He's going to have to do entirely different EQ moves and compression moves. And what I had done is I had tried to do it the easy way and just assign ox sends from each one of my buses and then print all of my stems at once. But that's great if you're going to be combining those yourself, but if someone else is combining them, they don't have that extra little bit of top boost or bottom boost that's on your two bus, so you're missing out on that. So anyways, yeah, this dude went to the label and he was like, sorry, man, this guy is going to cost you, or I need this much more money because the mixing engineer printed this in wrong.

(00:19:57):

And then of course the label's coming to me like, what the hell man? Why are you costing us extra money? And then I had to explain to him that, no, this guy's an idiot, but I'll redo it to save you guys money. I'll be cool about it. So anyways, I was probably in the wrong, but also that guy was just an idiot. Anyways, whatever you're doing, if you have stuff on your two bus and that's how you're submitting it to be mastered, make sure you have that stuff on there when you print the stems too. Otherwise, you might get that call one day five years later and they're asking you to export the stems, but you don't have that piece of gear or you don't have that plugin anymore and now you're kind of screwed. You'll definitely get one of those guys that's going to be a stickler for, oh, it sounds different. It's like a half db, too quiet at eight K, and it's like, dude, just EQ it.

(00:20:52):

Okay, next question, John. Random tangent, cdo, for whatever reason, this worst moment of sales in history, man, this is like in 2010 and we were touring on our second lp. We had got moved over from capital to Virgin, lost everyone at the label, and we were kind of like the redheaded stepchild at Virgin and they had no idea what to do with us. The original plan for us at Capital was kind of treat us like Metallica and try to get as big as we could and let the mainstream world come to us if that would happen naturally. The people at Virgin didn't figure that out, and they kind of dropped all their rock bands except for us Red Jumpsuit Apparatus and 30 Seconds to Mars, which they were both radio bands and we were not. So they had no idea what to do with us, so they had to just try to push us to radio.

(00:22:03):

And I remember one show our very worst show ever, we had to, it was like in Middle America somewhere, and we played a Qdoba Grill at lunch, and it was by far the most embarrassing thing. Well, I don't know. I've done a lot of embarrassing things, but one of the most embarrassing band things I've ever had to do was play a Qdoba Grill at lunch to five people and have no one care and just keep telling everyone they're mad at you because the guy making their burrito can't hear that he wants no corn on it or something. You know what I mean? It sucked really bad. Anyways, sorry John, but Keto reminded me of Qdoba. I don't know how I got there, maybe because the Q Anyways, Hey Beau, thanks for doing nail the mix and especially a big thank you for all the detail you went into.

(00:23:02):

The drum section was probably the biggest knowledge bomb we have ever had on nail the mix, so thank you. I have two questions for you briefly on nail the mix, you were talking about converters and how the apogee took something away when you heard your mixes back on other systems, I'm currently using Apigee duet, but curious, what interface would you recommend to someone in the three to $500 range, if any? Okay, so what I guess, let me clarify that. So what I meant by that is the Apogee stuff, I have a duet and I use it for lots of mobile recording stuff. When they used was looking for a new guitar player. I was doing their monitors for maybe like a year or two years. So I recorded all of their rehearsals for the people that tried out and every day I would give them to the guitar player and it was like, Hey, here's, I think the Apogee Duet sounds great.

(00:23:58):

I did a whole thing with the Bronx on the Apogee site. You can see a recording that we did with nothing but with a microphone into the Apogee, what is it called? I think it's called, not the Ensemble, but the symphony, just using their onboard preamps and converters and it sounded fantastic. My issue was that converters like the Apogee and Burl and a lot of those super high-end converters that kind of give you that extra five 10% while you're listening back to the A conversion, I find that if you're listening to that extra 10% and then comparing those convert, let's just say take a mix that you just worked on, load that mix into pro tools, hit play on pro tools and in your iTunes at the same time on your monitor controller switch back and forth between the two, you should hear a pretty big difference on, well, not pretty big, I'm definitely exaggerating, but I can definitely tell which one's which.

(00:25:08):

And when you're using those types of A or D to A converters, it's mainly the D to A, because the A to D is great, it's just the D to a that gives you that extra little bit of sheen that is not there when you play it on a regular system. So that was my problem with it. I would be listening to it and then I would import my mix into iTunes and listen to it compared to some other records and it was like, man, I'm missing that extra little bit of extra thump on the bottom and the sheen on the top. I'm missing that now. So that was a problem for me. And converters are a pretty big part of a sound. I did a record for a pretty famous producer named Michael bein Horn, and we had tracked the record on Apogee at the time. They were the DA 16 Xs and the ad 16 Xs, that's kind of like the previous version of the symphony rigs now. So we had tracked the record on that, and then I had taken the files back to my studio and I use the links converters. I just did the edits and then bounced out just kind of like a rough and sent that to him instantly. Sorry, if you can hear my dog snoring in the back.

(00:26:34):

He is like this 150 pound great Dane that just sleeps on my couch all day long and he loves to have band guys in here screaming at him and wailing on guitar. Anyways, yeah, so I did the rough mix for him, sent it out mind you didn't change a thing. All I did was just do the edits, like tune some vocals, tighten up some drums, et cetera. Sent the mix back from him. And mind you, there's no analog here. None of the plugins are different or anything. And immediately he had said something sounds off about the mix. It doesn't sound the way that the other refs, we've been printing at the other studio sound, what's different. And so ultimately it was the clocking. So what I had to end up doing is we bought a big Ben clock and we clocked my converters to the big Ben and then all of a sudden the character of those converters came back and then it was there. He was happy. So yeah, they can make a difference. But to answer your question, I think the duet is badass. I mean, I own one, they're awesome. I think that there's also the links, Hilo or Hilo, but I don't know what the price is on that. That's the only other one. There's also the antelope stuff and then UAD makes some pretty good ones, but I think you're set with the duet, man. I would stick there.

(00:28:07):

Okay, next question, sander Saddam, hey boat. What was it like getting CLA to mix the self-titled sales and record? Did you get to meet him and any cool insight into what he does or did on that record? Thanks. Yeah, what was it like having him mix the record? It sounds good. It sounds great. I will say, of course, my biggest gripe was at the time we were living in Orange County and his studio was in Burbank at the time, so it's about an hour drive ish, maybe hour and some change from our house in Orange County to the studio in Burbank. So his mixed session starts at around 10:00 AM which means we have to leave our house at nine and sit in traffic, but you can't just leave at nine because you have to be there at 10. So we had to leave at eight to make sure we were there by 10 because the last thing you want to do is, okay, big major label record, the band's supposed to be here and you don't want to be showing the label that you can't even show up to your own mix session on time.

(00:29:22):

So me and Chris go up there and we get to the studio. Everyone there was super nice. Chris comes out of a secret door somewhere, he is got a cup of coffee in his hand or something and he's like, Hey guys, nice to meet you. Thanks for coming up. I'm really excited. He was super nice. Hey, this is Shelly here, or whatever her name was, and she's going to be taking care of you guys today, so anything you guys need, just let her know. And oh, I think she just baked some cookies too here. Yeah, have some cookies. These cookies are great. That's her, that's her thing. And I was like, okay, great. This is cool. Then as we're, it's like that perfect opportune moment, as soon as we put a cookie in our mouth and start chewing and we can't speak, then it was like, I feel like it was so methodically planned out.

(00:30:14):

It's something that he does, but I could be wrong, but it was like as soon as we put the cookies in our mouth and we couldn't talk, it was like, well cool. Well, I'm going to go mix the song and I'll call you guys when I'm ready for you guys to come listen to it. So I'll see you in about two hours. And at first it didn't really hit us, but then after about 15 minutes, me and Chris were just like, wait, so you had us drive up here in traffic to be here at 10 and then you're going to tell us you don't need us till noon? Why would you do that to us? That sucks. And anyways, I even asked if I could go in there and it was very much like a no, you can't go in while he's mixing, which I definitely get because that's how I did a lot of my learning.

(00:31:02):

And I would've been for sure asking him questions like, Hey, why are you doing this? Why are you doing that? And I probably would've definitely gotten his hour and a half mix probably to somewhere around the three hour mark, so he would've hated me. But all that being said, we went and had lunch and then got back to the studio. He was ready to play us the mix. Me and Chris walk in, he hits play on the speakers, and I mean, it sounded awesome right from the get go. No real, no real notes other than like, Hey, we want to maybe have the background vocals up a little bit because we all sing. And I think that's kind of a unique thing about our band, which he was cool with and he was cool, but I think he also secretly didn't want to because it was very much like, yeah, could we get those up?

(00:31:52):

Alright, sure. Hold on. And it was like, I forget his, Chris maybe was his assistant's name was also Chris, I think. And maybe it was like Chris, but play that. Alright, cool. Let's go from the chorus. Let's pump these up a little bit. Alright, yeah, I think that's good. Alright guys, anything else jump out at you? And then I, of course I'm like, yeah, I think it's on the song collapse. And if you listen to that song right from the very beginning, the drumbeat is kind of like boom, boom, boom, boom. And you can hear what sounds to me. And now what I know is out of phase snare samples in there, and I mentioned it at the time, but maybe I was being a little too polite and acting like I didn't really know what was going on. And maybe that was the issue, I don't know.

(00:32:40):

But I had said, Hey, can we investigate maybe the snare drum because it sounds like maybe there's something weird going on. It's not really punching. Maybe it might be the bottom snare. I don't know. And then he kind of looked at me and then he just played a little bit of the song through his small little boombox that he had, and then it was just very matter of fact like, Nope, sounds fine, anything else. And right then I kind of got the hint that, okay, well we can only really ask for level up or down maybe, but anything else he's not really willing to touch or investigate. That was a little bit of a bummer. But I understand he does kick ass, so I can't really have too many bad things to say about him because he did a great job. So yeah, part B of your question, any cool insight into what he does or did on that record?

(00:33:36):

Thanks. Yeah, I mean, again, I've told the story before when we were tracking drums for that record, I had expressed some concern about the Tom tracks having way too much symbol bleed in them. And Howard the producer, assured me and made up this ridiculous story about how like, oh dude, you don't know what you're talking about. Chris Lord, algae, the bleed coming in. Our Tom Mikes sounds so fantastic that he actually uses our Tom Mikes as symbol mikes and I was just like, oh my God, you must think I'm an idiot. That's the most ridiculous thing I've ever heard. Anyways, skip to about six months to a year later, I get the multi-tracks back from Chris Lord algae. They've got all of his samples and everything on there, and what do I see? First thing I open up, I go to the Tom tracks, they're completely chopped out in the same way that if you have the silver string tracks the way the Toms were just completely chopped out.

(00:34:42):

So it was pretty, that was kind of funny. I was like, oh, you fucking asshole. I knew it. I knew I was right. But all that being said, yeah, I mean he still does. It's funny, I open up that session of his sales and mixes and if you watch his mix with the masters thing that he does, I think he mixes a muse song or something. It's funny, even down to the kick and snare sample, they're still coming up on the same track. It's like, I want to say it's like 41 and 42 or something. It's up there. But it was funny looking at that, watching the Muse session and then having the SAOs in the session up, looking at how his organization was still the exact same, exactly the same. There was actually no difference. I think the only difference was we didn't have the extra band submitted snare sample on there. He just used all of his own.

(00:35:47):

Okay, Eduardo Alexander Pando Desde, your question. Hey Beau, what's your approach to gorilla recording drums in a not so great drum room, specifically with the overhead, since they are the thing I struggle the most when I try to record anywhere else that is not my home studio. Thanks. And greetings from Mexico. What up Mako? I would say, yeah, I mean if you're trying to go gorilla, I think usually the biggest problems are coming from a crappy drum room is reflections that you don't want. So I mean, obviously the jerk answer or not jerk, but there's the dorky internet guy that's like, well, why would you record in a crappy drum room? You should just record on a great one. Okay, well, that's not the answer here, but if you have a good drum room, I would really ask them to do it at your home studio.

(00:36:42):

But okay, addressing your question, I would say build some gobos that you can take with you, even if they're small ones or decent sized ones. Bring them with you and put gobos all around the kit. Maybe bring some extra, you see those. Actually a great idea would be make the acoustical treatment in your studio kind of modular so that the base traps or the whatever trapping you have going on in your room is movable, and then you can bring those with you while you're at another studio. That would be a good two in one solution. You can build those as almost as if they're gobos, place 'em around your room for bass traps and then bring 'em with you, place 'em around the room as you're recording drums because you're really trying to just eliminate crappy reflections coming back and causing phase and weird buildups in your overhead mics.

(00:37:46):

So that's what I would say. Try to get the cleanest tones you can eliminating any crappy reflections if they are. But one other thing that I've been doing, I've had good luck with is if you're using your kit, if you have a house kit, then I would really suggest finding the ranges and notes that kit sounds great at. And basically if you know that the close mics on your kit are going to sound banging if they're punching and hitting in the right frequencies that you enjoy, or if you're going to be layering it with samples and that kit, the frequency or the pitch of those drums lines up or it responds well to the samples that you're going to be using, that's half your battle right there. So like I said, something that I had luck with was finding the tuning ranges that I really enjoy.

(00:38:51):

I recently went to a studio where I had not been before and the control room was, they just didn't have, the isolation was not great. So as I was tracking, I kept thinking like, man, I don't know if I can trust this control room. Something sounds a little weird, but in the back of my mind, I knew that my drum kit sounded awesome. And as you guys know, if you have an awesome sounding kit that's tuned up perfectly, you can kind of bowling ball microphones up to the kit and it's going to sound great as long as the guy's playing well. So I kind of went with that mentality, but I did the first thing. Another thing, another little trick. The first thing I would do is when you go to a new studio, listen to your reference tracks to kind get to know the room, but then also also take a sine wave generator and start down 20 hertz and just slowly sweep up and you'll be able to hear the room and where you're sitting.

(00:39:55):

Start to uncover all those peaks and nulls that are at your listening position and make note of those. Because if your snare is tuned and the fundamental is at let's just say 150 hertz, then if you have a big null at your listening position at 150 hertz, you're going to try to tune that snare differently or you're going to be moving mics, you're going to be doing everything you can to try to fix what you think is a problem with the drums, but it's actually a problem with the control room. You may end up making compromises that fix the problem in the control room, but then when you get it to your place, now all of a sudden you have this snare drum with and maybe all of your mics, you've positioned them somehow and there's so much 150 hertz hurts. So again, that sine wave generator is a pretty big pro tip, I guess going into a new spot, learn that room real fast.

(00:40:54):

It'll point out all the big peaks and nulls way more than a reference track. And the reason why that works better than a reference track again is because if your null is at, let's just say your null is down at 70 hertz or 80 hertz, and the kick drum that you're listening to for your low end type of thing is the fundamental is around 60. So you're not going to hear that there's that null at 70. So you're kind of tricking yourself into thinking that the room sounds good when in fact it doesn't. So again, learn those nulls. That would be probably even more important than bringing the gobos. Either that or bring a great pair of headphones that and then just turn the monitors off. Okay, next, Rodney, Rodney, Alton ba Dear Beauw. Hey dude, first off, thank you so much for the incredible month you brought to nil the mixed community.

(00:41:53):

In May, I think everyone was able to take away something that month. I sure hope so. I had a great time. Back to Rodney. First and foremost, thank you for inviting me to your studio to sit in and watch you work your magic. I took so much away from my visit to your studio in LA and we'll never forget it. Since my visit, I've learned that I am for one, mixing entirely too loud. Hearing how quiet you worked has opened my eyes and I'm eager to make these adjustments. Awesome. Yeah, I mean, I don't think I mix too quiet, but apparently compared to some people I do, I mix at about, what is it, 80, 75 or 80? I'd have to check anyways.

(00:42:38):

I think it's 75. No, it's got to be more. I think it's 85. Anyways, I have a mark on my monitor controller where I listen to, and I also have a noise meter right next to me at all times just so I can kind of double check and check myself to make sure I'm not listening too loud. I think it was actually CLA that said that one time, he's like, when you're mixing, you're working and you're not really listening to music for enjoyment. I guess you're mixing because you're working and you're trying to make something awesome and you're creating art or you're creating a technical side of things. But if you're listening loud, you're listening for selfish kind of like enjoyment. It's like, yeah, this sounds sick, cool, pump it up. But if you're listening quiet, you're forced to mix and work hard at it.

(00:43:32):

So something that I took away from, I kind of expanded on that and took this from a lot of the film scoring guys. They just stick one level and they don't touch it the entire time. So what that does, and the reason why I like it is because when your ears respond to music differently and they respond to sound differently at different levels, so as you raise and lower the volume of your monitors, the frequency response of your ears actually changes. So you can think that maybe you have enough bottom end when it's loud, but then when you turn it down now, because the bottom end is not accentuated in your hearing, that now you're focusing on mid range. Well, your mix should translate at every volume. It shouldn't matter how loud it is or what you're hearing. I and I get the argument that you're using the curve of your ears to hone in on certain frequencies.

(00:44:36):

I get that, but I just don't really subscribe to that. I like having one volume mix the majority of my song all the way through and then maybe check it really low, check it on a couple different monitors, and then check it loud, but only for a split second. I don't kind of blasting my hearing out too much. Yeah, so that's my opinion on it. Rodney's question. My question is actually about construction of your studio. I had a similar idea of building a small cottage or cabin, similarly similar to what you had. I'm just curious as to far as what dimensions and any guidance for going that route. Thanks again for keeping me up. Thanks again and keep up the good work.

(00:45:22):

You know, there is another question about this. I'm going to tag team these two, Patrick g Graff also has a question about the studio. Did you design and build the studio yourself? If so, what resources did you look up and read about to build the space out? So to answer these questions, Rodney, my studio, so it's a two car garage, but it's a big one. It's the biggest one I could build on my property. It's 20 by 30 and you need it to be huge. So you have to kind of build these things purpose built, because when I was building this, everyone thought I was crazy. I had 10 foot ceilings in a garage, and we're trying to pass it by the city. And it is so funny because LA is so, so weird, and the rules are just so stupid and everything you have to, all the hoops you have to jump through.

(00:46:15):

And you guys, I'm sure every city is like this, but I mean, it's so ridiculous to give you an idea of how ridiculous it was to build a new garage. And granted it is an old part of LA and I'm kind of just south of Hollywood. I'm in the thick of it, but in a little tiny five block little oasis, and it's all houses that were built in the early 1910s to 1930s. So my house is 1922, and the driveway is so small, you probably couldn't fit a truck down it. It's tiny. It's built for the Model T car to drive down that driveway. But now, so the rules are if you tear down your garage, which my garage at the time was pretty much just like a little shotgun shack or a large a king size outhouse, if you will. And to tear that down and then build a new one, the new codes for whatever reason, you have to build a retaining wall like a cinder block wall at the edge of your property. And I guess the reasoning for this is because some lady was driving down her driveway, granted it's like a very short driveway. So someone's driving down their driveway car somehow blows up and catches the neighbor's house on fire. So now of course, they pass a law that says, oh, well, we should definitely make everyone have this cinder block wall that separates their driveway so we don't burn other people's houses down.

(00:47:54):

Great, okay, fine. I can understand the logic behind that. But my neighbor has built onto their house illegally almost all the way up to the property line. There's like they're about a foot away from the property line. So they did not adhere to the setback rules, they just went for it. I don't know if this neighbor did it or the people that own the house before them, but somehow their house is one foot away from the property line. So I go to the Department of building and the Department of Planning, and it's so stupid how it's set up. So there's the Department of Building and Planning, I think, and then there's the Department of Safety. So the Department of Building and Planning says, you need to build a wall. Great. I get the plans to build the wall. I'll checked off. Now I take it over to the department of safety.

(00:48:44):

And the department of safety says, oh, sorry. Well, you can't build a wall because your neighbor's bedroom window is going to be blocked by this fence, and it's a fire escape. Technically, her bedroom window is a fire escape. Okay, well, do you want me to build the wall or not? I'll do whatever you want, but just tell me what to do. So almost six months go by of these two departments having a pissing contest of who's going to win this argument. Meanwhile, I'm sitting here just like, dude, I'll build the wall. I'll build, what if we do trap doors that she can open from her side, like little trap doors that she can open in case there's a fire? Oh no, we can't do that. Nope, nope. So anyways, long story short, we finally ended up just going to in a different city to get approved for the plans and just did a total dumb guy plot plan and pretty much drew the whole thing on a napkin and said, yeah, I just want to build a garage over here and this is what I'm thinking.

(00:49:51):

And the guy signed off on it, so it was so ridiculous. Oh my God. Yeah, it sucks. You want to build a big spot as big as you can, and I think every big studio owner will tell you, even if you have 10,000 square feet to work with, eventually you're going to say, I need more space. So, oh, that's where I was going with this. So throughout the planning, right, it's like I wanted to do 10 foot ceilings inside my garage because that way when I build my separate kind of pods that is my control room and iso boost shell inside of my garage that way, my shells would be nine feet, and then I could have a foot of trapping inside of the room of base trapping on the ceiling to bring my ceiling down to an eight foot ceiling, which feels normal. I feel like lower ceilings just feels a little claustrophobic to be in a room with five guys all day every day.

(00:50:52):

So that was important to me. So like I said, planning ahead, but it was just funny because as we're doing these 10 foot ceilings in here, the inspector guys are 10 foot ceilings in a garage, huh. That's a little, that's interesting. And then of course, the contractor's like, oh yeah, he's an avid kayaker or canoe rider or something like that. It's like, yeah, he wants to be able to park his cars in his garage and have his canoes still on his garage, so he doesn't want to have to take 'em off. It's like, oh, okay, that makes sense. All right, got it. Or then there's this other rule we had to do where it was the backup rule or backup radius or something like that. And since our lot is kind of a small lot, trying to turn around a car in the allotted area in our backyard is kind of tough, but we were able to get through it by saying that one of our cars, so for a two car garage, one of the cars has to turn out and be able to make a two point turn to get out down the driveway, and we actually used the turning radius of a smart car, so we were able to get in there and it's like, Hey, man, the rules just say you have to have the turning radius of your car has to make this turning radius to be able to get out in this space.

(00:52:08):

This guy wants to buy a smart car. So that's the turning radius we're going to use. I found that really hilarious. It was kind of a dumb thing. But anyways, yeah, I did end up building most of the construction myself. I had a couple friends helping me full on just trying to make it so the neighbors didn't know very much, and it was like I would have Home Depot just delivering huge pallets of five eights drywall. I would have 'em deliver it as deep into my driveway as they could, and then I would have three friends there with me to hustle up and get everything moved into the garage as we were building everything, and it was pretty fun. And then I have a friend who is a electrical contractor, so he came in and did all of the electrical stuff for me, which he thought was super, super funny and also fun because I also have separate isolated grounds on different circuits, so you know what I mean.

(00:53:04):

It was kind of fun for him to do. Then the room went through a couple different changes between different kind of styles of room. I finally found this type of room, there's a good book by this guy named Philip Newell, and that's kind of the room that I have. So I had a room that had the non environment and with the flush mount speakers in the front of my room, if you go on my Facebook or Instagram, you can kind of see what the room used to look like and there'll be a console in there that I used to have. But eventually my room was just too small to have those huge speakers in here. I mean, it was like dual 15 inch speakers mounted in the wall, and it was huge. So got rid of those, redid the room, had this guy named Herman Virgen out here in LA helped me.

(00:53:53):

He's done a lot of studios out here. He kind of helped me come in and kind of finalize it and dial in the room, and that's where I'm at now. But my control room itself is only about 19 by 16. And if I could do it again, my advice would be don't follow any of the, oh, you need to have your walls splayed or angled or any of that stuff. It's all, I get what people are saying by that. But when you do that, you're just creating more problems in the sense of trying to treat your room. One of the great things about a rectangular room, if you have the right dimensions, it's going to sound great with minimal treatment. So there is a forum that you can go onto. It's the John l Sayers forum, and you can run all your ideas by those guys, and they're just nothing but acoustics and studio building dorks that are just on there, and they just love to help you.

(00:54:56):

You will definitely get some of those, anything you're going to get those answers. It's like, Hey, I'm trying to build my studio in a five by 12 closet. How can I treat it? And people are just going to be like, yeah, that's bad idea. Don't do it. But you can at least find a lot. I would read all of the studio build threads that are in there and try to pick and choose information that's relevant to your situation. But yeah, if I had the idea to do it again, I would probably do the whole garage, like a huge control room, and then maybe build a small ISO booth at maybe one of the back corners or back center of the room to throw for amps in there or figure out a way to isolate amps somewhere, or maybe even dig down underground and make an underground kind of basement area for guitar amps to just live in.

(00:55:50):

Especially with the micro robot, it's like you never even need to go down there now. So anyways, yeah, and then Rodney says, PS my family is now interested in a bidet for those of you, thanks. So for those of you that don't know, a fantastic studio essential is a heated toilet seat and a bidet, and it's just, it's fantastic. I won't even use the toilet in my house anymore if I have to take a dump. I go out to the studio and I walk upstairs and I sit on my heated toilet seat, and then I give myself a nice wash when I'm done. And it is just for all of the crap that we have to deal with as audio engineers, people yelling at us or making just unrealistic demands.

(00:56:41):

That nice heated toilet seat and the H2O wash at the end just makes it all worth it. Also from Patrick Graff question about the phase trick to clean up drum bleed. Why do you EQ the source before you do the phase trick? Is this to help give a difference between two signals, or is it just to save time once you've printed the new cleaner track? So first off, you don't want the signals to be different at all. And if you understand how this trick works, you're understanding that EQ deals with phase. So if you take the track that you high pass and compress, if you take that track and eq it differently than the track that is not high passed and not compressed, that's going to make some phase issues between those two tracks. So if you're going to be adding top end to one, make sure you duplicate that plugin on the other.

(00:57:43):

The only thing that should be different about those two tracks is the high pass filter following the compressor. That's the only difference. Everything else you want the same, otherwise you'll get weird bleed and weird response from it. Another trick that I've kind of been hip to is someone mentioned potentially using a transient designer before the compressor to help quicken the attack, which was a kind of cool trick or even sometimes using limiter. So it is pretty much a trick that'll work every time, but sometimes, depending on the source, you may have to give it some more transient to get there or maybe even knock some off. Eric Howell, he says, Hey man, I love your work. I was wondering what kind of amps you used on the Moose Blood album, and what are some tips on getting that not very distorted tone to be full and powerful enough to drive a mix?

(00:58:48):

I've also got another ax effects question below, so I'm going to combine these two. Matthew buys says, I've noticed over the years of trying to get the perfect guitar tone out of Amp Sims that the cabinet impulses can take a tone from muddy mess to completely usable without even touching the amp settings. What are some of your favorite impulses from the ax effects for the medium gain type of tone that works well with big cords? Or do you prefer to run it through a real cab and mic it up? Thanks. So Matt, I haven't really ran the ax effects through a cab yet because to me, the acts effects is all about convenience. It's about, here's this tone, it's already dialed, it's saved. I know it works. I can use this. Or it's about finding tones that might be more difficult to do in the real amp world.

(00:59:40):

For instance, that bass trick, two separate amps. It's like, well, obviously that's going to be kind of a nightmare to do all of that at once and keep everything totally in phase the way that it is in the X effects. So to answer both of your questions, the trick to getting the low gain stuff but without being super muddy is all about your input filtering. And so for ax effects on those types of tones, like the moose blood stuff, you're not going to believe me, but a lot of that stuff is actually neck pickup or middle position pickup. And usually neck pickup on distorted guitars is almost unusable. It's just so much mud because the tone is just so full and whatever warm, but to me it's just muddy. So the first block is always an EQ block with a big mid bump and usually a high pass filter or a low cut, whatever you want to call it, just hucking out a bunch of that low end that's just eating up the headroom of that amp and then all of a sudden you'll start to notice that the muddy cabinet impulse you are kind of thinking is the problem is no longer the problem because now that muddy cabinet impulse response is actually giving you the kind of bigness and low end mud that would be missing if you had a very clear or pristine sounding cab.

(01:01:21):

So I mean, that's how I like to deal with it and that's how I work with those. That's how I did those. And then you may have to EQ it a little bit more after the fact to on the actual amp, so in the amp block you can actually go in there and mess with the graphic EQ that's on there. And I think that the graphic EQ that's on there sounds, if you're going to add, let's say 4, 6, 8 K up in there to get some brightness, I think that that sounds totally different than if you were to add it after the fact. So trim messing around with that stuff too, and you can cut out some of the, that's actually another good place to experiment too. You can kind of cut out a lot of that 2, 4, 2 and 400 area by using the graphic EQ on the amp blocks themselves.

(01:02:11):

But the trick to, I would say in general, the trick to great guitar tones or getting those types of tones to work is having everything work together. I recently got asked to produce another record based on the drum sounds for that moose blood record. And it's funny because the type of band it was, those drum sounds are not going to work with the type of band that they are. So it's funny, it's all about making the tones work together. I mean, to me that's the biggest accomplishment or the biggest goal that you can have is getting a bunch of cool sounding tones to really work together and make them all feel great. So yeah, sometimes the key to a great guitar sound is actually a cool drum sound that supports it. Or sometimes the key to a making a muddy guitar sound, sound great is maybe letting the base take a backseat, different ways of looking at things.

(01:03:22):

Michael Cooper. Hey Beau, can you explain your joking? Can you explain your vocal tracking approach? I was actually just talking about this with someone the other day and I think there's a couple different approaches. A lot of people kind of from what I hear, a lot of people will say like, yeah, man, sing the song eight times and I will comp it together. I think that personally, I think that that is a huge waste of time and chances are, if they've been rehearsing a song and singing it one way, the thing that you don't like about the first take or the seventh take is going to be in every take because that's just how they've been doing it. So my way of working is I have the singer come in, show me what he's got. We put down, we do one take of sing the song all the way through, show me what you've got. If you don't have lyrics for that section, just give me some Lotty Dody do or just free ball some stuff.

(01:04:18):

We do that. I take a listen to it, I make notes, I present those notes to the singer. We talk about which notes we want to implement. Then we go back, fix just those parts, see how they sound. Obviously there's going to be some things where it's like, hey, you're saying turn off the lights and I want you to say turn off the lights. Just different phrasing things depending on how the drums are moving. Or maybe I might want 'em to say, Hey, this song is kind of like the same chords throughout the whole song. It doesn't really go anywhere. So maybe to differentiate the verse from the chorus, let's maybe have the verse all starting on the one or on the downbeat, and then let's make the chorus kind of come in on the upbeat afterwards to give it kind of a slightly different feel.

(01:05:05):

But we'll keep your melody and lyrics all the same. So sometimes I might give a note like that and the singer might be a little bit confused or I get what you're saying, but I just have to hear it. It's like, cool, let's just try it and then we'll listen back and see if we like it. So that's basically what I do. I do that kind of pre-production all at the same time as I'm going through and tracking. Once we get that done, then I go through and as many lines in a row as he is capable of singing, then we'll do, so we might just do one line at a time. We might do a whole verse at a time. It really depends on the song, how long the verses are, how long the lines are, how much breathing is involved, where the notes are in the song.

(01:05:53):

Let's just say it's a screaming part. We might save the screamings for last because he knows the screamings is going to blow his voice out. He knows that he can't sing high notes, so we'll do the high stuff last, so we'll skip those if there is any. It's all about trying to work to where the vocalist is going to be able to give his best performance and whatever he's or she is, I don't even know why I say she, I mainly work with he's, so whatever they're feeling is the most important to me. So yeah, we might do a couple lines, do those a couple times, and I go for the take that I want. So if I am hearing him saying, Hey, those are my whatever m and ms, then I'm going to say like, Hey, I don't like how you're saying my, it gives me a weird, I'm listening to it in context of the mix, and all I can hear is E, it's like this kind of three K ring that's happening when you do that with your mouth.

(01:06:56):

So can you maybe try to say, can you please give me my and make that kind of more of a ma instead of my type of sound? And I'll work on a lot of those things with them to make them kind of sound their best in the track. Then from there, we may even have to sing that same May 15, 20 times until we get it right. But I'm looking to get a good take to where once almost getting a guitar track, you know what I mean? You're punching in for certain notes and if you can't sing it all, if you can't do it all in one pass, then we'll just get it one for that one thing, and then I'll just treat every line like that. And then once I get the whole main vocal track done, I'll have the singer give me a double of the whole song.

(01:07:47):

I may or may not use it. I kind of treat that like a safety net just in case there's something that when I go to tune it, if for whatever reason I misjudged myself and I thought I could tune a note, but when I tune it, it sounds weird to me. So at least that way I have one extra backup safety net word or a line that I can tune and hopefully that one will sound good. But the majority of the time now I'm so used to, and I know my limits of what I can fix. I rarely end up using it unless I want the double there as some sort of double effect to kind of blur the vocal a little bit. My favorite vocals are always just that nice dry, ultra compressed upfront vocal that just sounds like he's in your face singing to you only.

(01:08:38):

And then from there, once I get those done, I'll tune and time all those, get 'em feeling exactly how I want. Then I'll go through and we'll do all the harmonies. I normally double all the harmonies, so if it's a part harmony, then there'll be six tracks. So I always do a stereo if it's like a mid harmony. So I'll have mid harmony left, mid harmony, right. Those will be hard panned if they're in the chorus for a verse, I may pan them in a little bit so they're not distracting, but I guess that's mixing. You're asking about my tracking process. So yeah, I'd normally double up all the harmonies just so I have 'em and I can put 'em anywhere I want. Okay.

(01:09:21):

K, C, C. When you receive multi-tracks from someone else, how do you determine which to use or do you use all of them? You're awesome. Thanks for doing these dear bows. Thanks Casey. I'm parched is what I am. This talking businesses is no joke. How do I determine which to use? I normally use most of them. The one thing I rarely use is guitar. I got sent files once before and I knew something was a little fishy when I downloaded the files and the zip file was only 200 megabytes and I was just like, what is going on? I opened up the session or I imported everything. The drums were all middy, the guitars were just di, the bass was di, and then there was just vocals. And I don't really like to mix things like that. I like to me that's producing, if I have to pick which drums you're going to play, to me that's producing.

(01:10:28):

If I have to pick which amps you're going to play, that's more like producing and that is a totally different side of my brain than mixing. So that being said, guitar normally don't use those. They'll still be in my session, but they'll be inactive and hidden. The base mic, I'll definitely listen to sometimes if it's a character that's really cool and I want to keep it and the band wants to keep it, let's just say the character's really cool, but the bottom end is kind of farty. So I might just high pass their character of their base mic and then use my low end of my ax effects tone to supplement the low end.

(01:11:15):

The only mics that I feel like I usually don't use is kick like NS 10 mic. I feel like that microphone is always just a bit slow and late sounding to me just for whatever reason, the way I want to hear a kick drum, it's never with that. It's like the Ns 10 mic is always just kind of, it's never loud enough. And then when you get it to the point where you're like, yeah, this thing's starting to slam, then it's too loud and it eats up too much of your mix. So I find that I have better luck with either layering in a low subick sample or using a plugin like low air or low ender to try to get that sub in there. If the other mics aren't giving it to me, that and then the mono room mic in a mix where I'm going for clarity, mono room mic normally gets cut.

(01:12:10):

If I have the option of stereo room mics, I'll usually always go for stereo room mics over mono most of the time. And the reason is because I like to smash my drum room mics and if I have that constant kind of room symbol sound of like that going in my center channel, that's just totally competing with my vocal and everything else in the middle masking a lot of stuff. And I've noticed every time I just mute that mono room mic, all of a sudden the mix opens up and it's just clarity central. So I don't usually delete it, but whether or not it actually makes it to the mix bus is sometimes questionable If they have stereo mics, if I'm forced to use a mono room mic, I'll normally probably duplicate that and then pan one to the left, going to a reverb and then pan one to the right, going to another reverb.

(01:13:13):

And the reason why I'll use two mono room reverbs is because to me that sounds a little more stereo than just assigning the one mono to a stereo room reverb. I think there's something within the algorithm that since you're sending the same frequency to both sides of the reverb, I feel like it just feels more narrow and I don't feel like a difference of left and right. And then for guitar tracks, if they send me guitars that have eight mics on, I'll normally just go back to them and say, Hey man, I need you to print the tone that you guys are working with because right now you're just giving me eight different ways to screw up your tone. And especially if the mics aren't all in phase with each other or there's a weird thing that's happening, well, actually, you guys probably experienced this with the Taylor Larson guitars and the Chuga guitars.

(01:14:12):

So there's all those tracks that you have and there's absolutely no way as an outside mixer to know which ones are supposed to be where. So that's why I make the producer, if I'm just mixing, I make the producer make the call, which is going to go where, tell me where I need, because I feel like my best work is done fast at the beginning of the mix going with my gut. And if I have to sit there and mix four different guitar tracks that are essentially the same guitar, it's kind of that's a part of my brain I don't want to use to use that energy on that. I'd rather it be, okay, well how can I just make this guitar, my two guitar tracks sound better? Why do I have to start implementing other tracks then working on automation between four different amps?

(01:15:04):

It's just, to me, that's a lot of work that is not really necessary for what I would like to be doing. Next up Santiago Romero, did you plan from when you were young to become a record producer and play in a band at the same time? No, I didn't. I had no idea what a record producer was When I was a kid, I would just walk around the house with a broom doing big old windmills on my guitar or on my guitar. I still think it's a guitar on my broom. And I would always tell him, it was like, I just want to be a rock star when I'm older and now I want to be the exact opposite of a rockstar and I want to be the guy that sits here. And I have this kind of joke that I say with a couple different friends and it's like, man, I love making music.

(01:15:56):

I hate being in a band. And what I mean by that is there's so much crap that goes into being in a band and having to make the different parties in your band happy. You know what I mean? And there's so many of those things where it's like, oh, well this guy doesn't really contribute, but I really want to make him feel like he's part of the band. And there's all this stuff you do throughout your band life when you finally look back and you're like, wow, that was a lot of wasted effort on just kind of doing band stuff when I could have just been making music the whole time and doing things that I really enjoy. So anyways, all that being said, I'm making the band seem like, or being in a band in general seem like it's crappy, but it's actually very fun.

(01:16:47):

But I think when you compare it to the whole being your own, I guess that's what it is. When you're producing records and mixing your records, you're judge, jury and executioner, you get the final say on everything. But then when you're in a band, you have five other guys that you have to reason with and you have to keep them happy. And sometimes you get outvoted. Sometimes I get outvoted on mixing whether or not I want something to be the focus versus this to be the focus or if that harmony is good or not. But when I get outvoted in that situation, usually it's because the ban normally has a good idea and a clear vision of what they want, and I actually was wrong. So I actually enjoy those moments when I get out voted because I feel like I learn from those situations.

(01:17:38):

And I guess that's something else too. I feel like whatever situation you're in, you should always find something that you can walk away from it and learn something from, whether it be like, oh no, man, we actually really want that guitar part to be obnoxiously loud. We want that. That's the whole part of this song that we want to stick out. And it's like, oh, really? Okay. I thought the guitar sounded pretty crappy, but I was trying to tuck it and they're like, oh yeah, no, no, it's supposed to be crappy. That's what we love. We really want to accentuate that. I'm like, whoa, okay, that's not what I was thinking, but let's go for it. And then you try it and you're like, that's actually pretty cool. It makes that crappy part now sound intentional rather than you trying to hide it. So yeah, making music's awesome, having to deal with people is what sucks. I shouldn't say being in a band sucks because touring and making music and getting to travel the world is actually pretty awesome, but having to put up with people sucks.

(01:18:43):

Next question, Sidharth Subramanian. Sid, let's call you Sid. I really enjoyed listening to the tips and tricks you mentioned on how to avoid errors slash correct them. Could you elaborate on a trick you mentioned to hear pumping, for example, putting a mix into mono and flipping the phase on the left and right channels. Are there any other similar tricks that you use to check yourself and find errors in your mix? I mean, that's a great one. I like using that to analyze records a lot. I was just talking to someone online yesterday and he sent me a mix to listen to and I was like, man, your snare reverb is just, sounds like it's coming at me from 360 degrees. It's just surrounding me. It's crazy. I'm not sure if he could quite hear it in his listening environment. So I mentioned doing that trick. I was like, Hey.

(01:19:46):

And I think he was referencing like a Taylor Larson mix, and I had noticed something about, I don't know if he does it on all of his mixes, but one of the things that I noticed, or at least that I think I've picked up on is that a lot of his drum ambience is kind of panned in the center. The drum rooms and stuff aren't really that wide. And the way you can kind of check those things is, like I said, you'll take your mix, dump it down to mono, and then flip the phase of one side of your mix. And what that does is it eliminates everything that's in your center channel. So the only thing you're hearing is your sides. I mean, I guess it's the same if you were to use a mid side processor and then just mute your middle channel.

(01:20:37):

But I told him to do that and it was funny. I think he replied back and it was like, oh my God, you're totally right. All the drum ambiance in that song is totally up the middle. It disappears when you do that trick. And then I did it to mine and all I hear is snare reverb. So that's just kind of a cool trick to see what's going on in your side information. You can also do the same thing by using a mid side processor. Even looking at your center channel versus your sides is kind of interesting. But those are just kind of things that I've kind of seen different mastering guys utilize mid side stuff and then realizing the power of analyzing what's there. So that's kind of cool. Let's see, something else. Yeah, so one time I had a dude, I was mixing a record and I kept getting notes back from this singer and all of his notes had to do with, it was kind of like an indie rock band, and a lot of his notes had to do with the shakers and the tambourines and weird percussive elements way up in the 10 to 20 K range.

(01:21:51):

And every time we would listen to them in the studio, it would be great. And then he would take the mixes out to his car and he would be like, man, I don't know what happened. The song is ruined and all I can hear is hi hat, or All I can hear is tambourine and it's just this really piercing top end. So we couldn't figure it out. I finally go, I have him bring his car over. I go sit in his car and listen. Lo and behold, boom, high hat is just ripping or tambourine and shaker, all that stuff, everything up in that range. So what I did is I got back into the studio and tried to kind of mimic the EQ curve of what his car stereo sounded like, and I started trying to figure out a way to make my monitors sound like his car stereo and recreate that problem.

(01:22:47):

What I found was that in his stereo, there was some sort of huge high frequency boost combined with the classic aftermarket tweeters. So what I did is I put a huge 10 db shelf at six k, I think, and what it enabled me to do is really hone in on that really high frequency stuff. And of course there it was poking out like crazy just so I've now taken that kind of one step further and when I check my top end, I still kind of do that thing. And the reason is I want my mix to, and it's kind of the same reason why I don't really low pass guitars too much because if someone hears my mix and they hear it on a system with a lot of top end, I don't want that changing the mix. I don't want just my high hat or just my symbols being super loud.

(01:23:52):

I want all of my mix to be just bright. Does that make sense? I want it to be balanced. Something you can do, throw that high shelving on there, crank it up real loud, then go through and listen to anything that's poking out at you because at a reasonable volume, your mix is going to sound balanced. And those few things like the shaker and tambourine track, that really high frequency stuff that's up there, it's not going to be bothering you because it's relative to the rest of the track. So when you boost that up, it kind of sheds a light on what is really happening way up top. So that's something that I've found to where I've been able to get my mixes a lot more consistent no matter where they played back by just kind of examining that top end and giving me that boost.

(01:24:45):

And then the way you fix it is whatever is poking out, let's just say you're going over the section where it has the shaker in it and the shaker is just somehow really bright in that kind of 1215 K area. So you just go on your shaker track and duck it down in those offending areas and only get the offending areas, the only thing you're after, and then you duck those down and then take the high pass filter off and it should sound the same as it did before, but just now just more smooth. So when you have that high frequency shelving on your master bus now it's like, wow, the whole thing still feels balanced and nothing's popping out. So that's just one way of making sure that your stuff translates from system to system.

(01:25:34):

One other trick I'd say for checking sub low end stuff. So I finally got my subs set up in here, so I actually have stereo subs now, and I'm pretty good on low end. And when I say I'm good on low end, I don't mean I'm badass at doing low end, I'm saying I can hear low end fine in here. So if you don't have a sub and your speakers go down low enough, you can do the whole check the sub trick by just low passing your master fader, go over to it, assign a high cut, bring it way down to 70 hertz or something or 80 hertz, and just listen to what's going on down at that level. Obviously it's going to be much quieter than if you were to have an actual sub pump in your room, but if your speakers go down to like 30, 40 hertz, then you should be able to get an idea of what's going on down there.

(01:26:32):

And if your speakers don't do it, you can listen to it on headphones, but it's really just a way of kind of honing in on those areas to see how your kick and your base is punching together. But without being, let's see, I don't want to say yeah, I guess without being deceived by the attack of the kick drum, because as we know, especially in rock, you take away that attack and then a lot of the times you almost can't feel or can't hear the kick drum. So I think it's important to make sure that you can feel the kick drum without having that attack in there. The whole thing with mixing, it's all just a big illusion and how you can make people think things are bigger than they are or smaller than they are if you want. So hopefully that's good for you.

(01:27:16):

Sid, last question, Brandon Gregory. Hey Beau. I'm a live sound guy and I've been doing it for a few years now. One of my goals is to tour with bands around the world, but every band who has asked me about working with them want me to provide a full sound system or work for free. Being that you are in such a big band, what are some things that you guys look for in an engineer to go on tour with you and how would you suggest someone go about getting those kinds of opportunities? I hope that makes sense. Thanks Brandon.

(01:27:54):