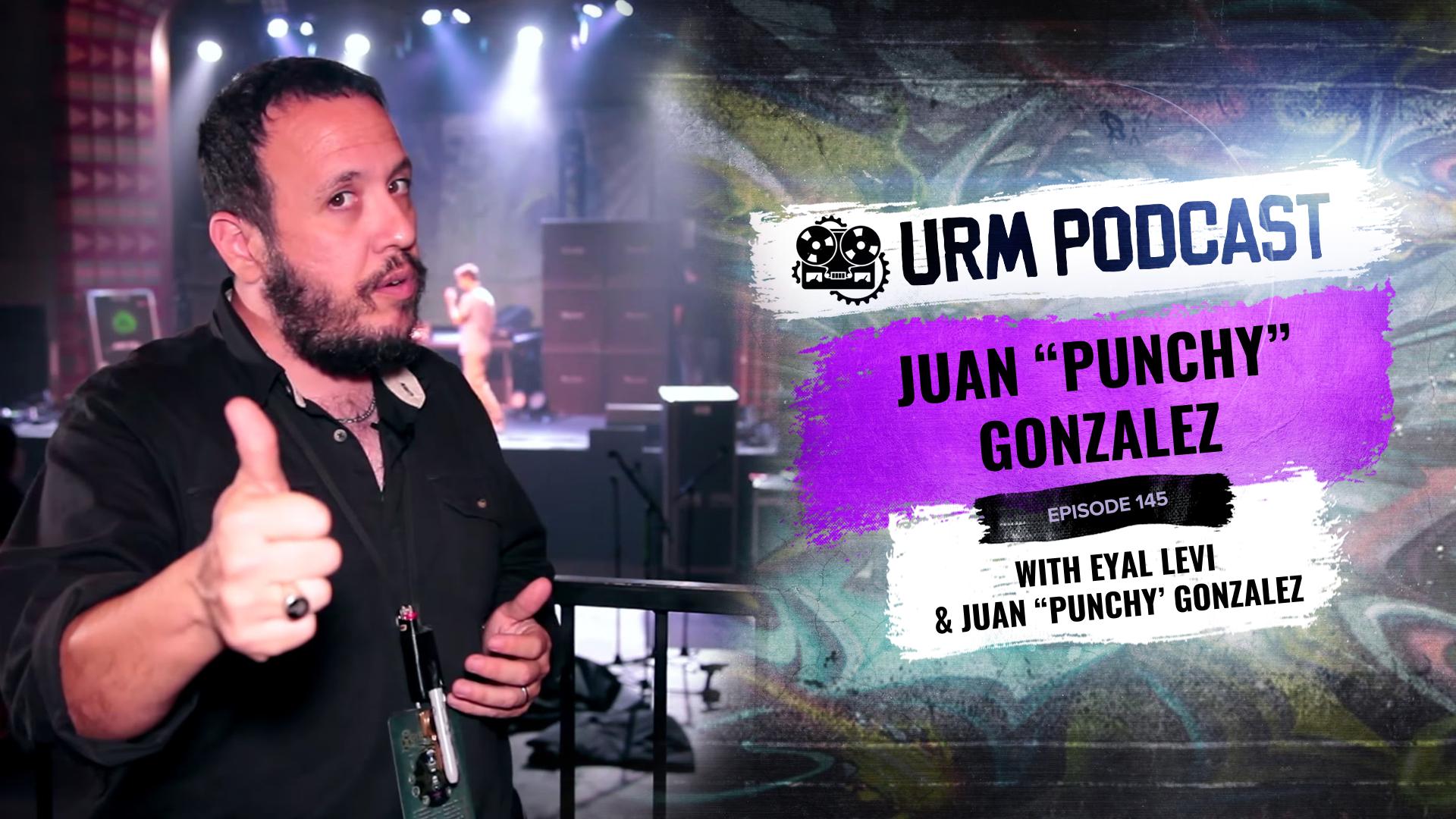

JUAN “PUNCHY” GONZALEZ: Taming chaotic metal mixes, tour survival secrets, and dealing with promoters

Finn McKenty

Juan “Punchy” Gonzalez is a veteran live sound engineer and tour manager who has spent decades on the road. Known for wrangling a killer FOH mix for some of metal’s most chaotic bands, he’s served as the long-time audio engineer and tour manager for death metal pioneers Morbid Angel and has toured extensively with acts like Nile, Symphony X, and Overkill. Beyond his live work, Punchy has also worked on records, directed a documentary for Morbid Angel, and now serves as the head technician for the Capitol Theatre in Florida.

In This Episode

Juan “Punchy” Gonzalez drops by to share some serious wisdom from his long career as a FOH engineer and tour manager. He gets into the nitty-gritty of why mixing extreme metal is so challenging and shares his philosophy on treating the console like a musical instrument to bring clarity to the chaos. Punchy offers some killer, no-bullshit advice on everything from the psychology of creating a consistent pre-show vibe to the technical differences between mixing in a tiny club versus a massive open-air festival. He also covers the non-audio side of the business, explaining why it’s crucial for bands and crew to run a tight ship, how to properly advance shows, and the right way to approach jaded promoters. From insane stories about mixing Overkill for a quarter-million people in Colombia to the realities of touring Japan, this episode is packed with practical lessons on professionalism and survival in the live sound trenches.

Products Mentioned

Timestamps

- [00:09:00] Why bands shouldn’t complain about working in union venues

- [00:12:00] The philosophy behind pre-show music and why the “metal DJ” is the worst

- [00:15:45] When the band’s epic intro sounds better than the band itself

- [00:19:08] The difference between mixing in a small club vs. an open-air festival

- [00:22:20] Viewing the mixing console as a musical instrument, not a “set it and forget it” tool

- [00:26:49] The story of mixing Overkill for 250,000 people with no prior experience with the band

- [00:30:00] Mixing a massive festival from a “sniper tower” off to the side of the stage

- [00:45:18] How legendary producer Tom Morris did drum replacement with tape machines

- [00:52:29] The strict rules and cultural expectations for touring in Japan

- [00:57:00] Surviving the chaotic, five-minute changeovers on Ozzfest 2007

- [01:07:16] The best and worst things about touring Europe (including sweaty cheese)

- [01:13:08] Top tips for a band going on their first major van tour

- [01:19:28] The hard reality for local bands trying to book out-of-state shows

- [01:30:19] Punchy’s process for tuning a PA system in a new venue

- [01:39:01] Why on-stage monitor discipline is more important than having in-ears

- [01:41:06] The mind-blowing, ahead-of-its-time MIDI rig of T-Ride (feat. Eric Valentine)

- [01:50:35] A passionate defense of using guitar modelers in a live setting

- [01:57:44] How to deal with jaded promoters who have “seen it all” and don’t respect you

- [02:02:41] Why you should never smell like booze or dope when settling up with a promoter

Transcript

Speaker 1 (00:00:00):

Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast, brought to you by Drum Forge. Drum Forge is a forward-thinking developer of audio tools and software for musicians and producers alike. Founded on the idea that great drum sounds should be obtainable for everyone, we focus on your originality, drum forge, it's your sound, and now your host, Eyal Levi.

Speaker 2 (00:00:22):

Alright, welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast. I am Eyal Levi. With me is someone that I've known for a long time. One of my favorite people in this weird ass industry, Mr. Juan Punchy Gonzalez, who is kind of like a renaissance man. I'd say that that's a accurate assessment. I knew him as a front of house engineer at first, a really, really good one, who knew how to make the most chaotic sounding, extreme metal sound like music in situations where it shouldn't sound like music, like large outdoor venues. Then that turned into me knowing him as a tour manager and tour managed me on some overseas stuff and basically say my ass. Then I realized that he also had a studio and made videos and now I think does live sound for theater. He is done all kinds of different things and he's got an excellent singing voice. So punchy. Hi. Hi y'all. How are you, bud? I'm all right. My life's a lot different than last time we hung out. Have this whole unstoppable recording machine business going, and I don't record anymore more focused on showing people how to live their lives in audio rather than making audio, but I am loving it.

Speaker 3 (00:01:58):

So you're out of the game completely. I mean, I know you're doing this, but you're out of the game completely. You're not making records, you're not doing none of that.

Speaker 2 (00:02:05):

No. Zero. Wow. I stopped at the end of 2014 so that I could build this. I just kind of figured that I'd take a year to build it and then jump back in or whatever, but it quickly became clear that you can't build something like this and also record at the same time. It's too taxing. The recording is too taxing or this is too taxing. Both of those require you to be a hundred percent, in my opinion, to do a good job. You have to kind of have to commit yourself fully. At least I do. And with this, we have some seriously lofty goals of trying to get to number one in online audio education in the next five years, and I can't really be doing something else that requires me to really myself.

Speaker 3 (00:03:09):

When you're mixing and shit, you're basically sitting at a computer for 10 to 12 hours at a shot and fixing audio and realigning drums and doing all kinds of nonsense. So it definitely is taxing.

Speaker 2 (00:03:24):

Yeah, and when you're done, at least when I was doing that full time when I was done, I didn't have anything left to give.

Speaker 3 (00:03:31):

Oh yeah.

Speaker 2 (00:03:32):

For anything else. So yeah,

Speaker 3 (00:03:34):

It'll beat you up.

Speaker 2 (00:03:36):

It'll definitely beat you up. I think that the thing is I've always, I'm not really into dumb quotes or even smart quotes. I don't really think that you can, I guess, simplify life down to quotes. But here's one that really worked for me, which is that you can do anything you want in life, but you can't do everything. And when I heard that, that kind of hit home because it's like, yeah, there's so many different things. I have the ability or the talent or the brain power to be able to do. I'm kind of lucky that way, but I still have to deal with this thing called time that we all have to deal with and have to make choices as to what's important and what has to go by the wayside if I want to be able to see something coming to reality. So here we are Now, what about you? I've been ranting by myself.

Speaker 3 (00:04:35):

Okay. Well, in 2015 I got married again. Congratulations. Thank you. And she's a wonderful Italian woman and she moved from Italy to the United States to be with me, and then I continued to be a touring guy. I mean, I would still do mixes and mastering and stuff like that in the studio in between tours through all that time. But I was still a touring guy at the time. And so in September of 2015, while I was out with Symphony X, I got a phone call from my wife and she says, I'm very pregnant, it's a boy. And I'm doing April and about a week and a half later I get a phone call from a company called Ruth Ecker Hall Inc. Which is a performing arts center down here in Tampa, St. Pete, Clearwater area saying, Hey, the house position at the Capitol Theater was open, and would you be interested in applying?

(00:05:42):

And of course, I mean, I had to take that opportunity because being able to be home and raise my son, this is my first child. So at age 45, I'm becoming a dad for the first time. I was 44 at the time. But becoming a dad at the time and saying to myself, my God, I don't want to see my kid grow up on Skype. I know so many dads and moms too in the touring world that they can't spend any time with their children and other people are raising their children while they're out there earning a living. So I count myself to be one of the blessed ones to be able to be home and still do what I do. And as the head technician at the Capitol Theater, I wind up mixing about 30% of what comes through there. The rest of the time it'll be visiting engineers guys at basically what I used to do. So I've been doing that pretty much for the last two years, and it looks like that's pretty much what I'm going to be doing for my main source of employment for the coming future. So it's a little different from touring except for the fact that now I get to play the role of the house guy dealing with my former counterpart, if you will.

Speaker 2 (00:07:02):

And how interesting is that? Because at least, I mean, it's got to be different though than when dealing with some house guys on the metal chores.

Speaker 3 (00:07:14):

Oh yeah. Number one, this particular theater just recently went through, well, a couple of years back, went through a 10 million renovation. So everything in there, even though the theater was originally built in 1921, everything in there is brand new. And there's, it's not dirty at all. It's not like a dirty club with penises drawn on the walls and all that stuff like that. You know what I mean? It's a real venue. It is super nice in there. And most of the acts that we, I mean, to give you an example of some of the acts that come through there, we had Olivia Newton John last month, and we had last year, Tony Orlando, and then, but coming up real soon, we have Anne Wilson of Heart and VE Stein, VE mean amazing Ace Fraley. And a lot of what comes through are guys that won Grammy's like 30 years ago, and they're touring on their one hit that got them their Grammy, that kind of thing. A lot of that is what our artist base is for the venue. But we are an actually union affiliated room. So I'm a member of the stage hands union and all of the labor that's there is unionized. So it's one of the more, there aren't that many club size venues. Our capacity is 725. There aren't that many club size venues in the United States that are unionized and we are. So that's something I'm actually rather proud of.

Speaker 2 (00:08:46):

Can you talk about that a little? Because I know a lot of bands hate playing union venues.

Speaker 3 (00:08:53):

Well, they hate playing union,

Speaker 2 (00:08:56):

That's all I know. I have nothing else to say about it

Speaker 3 (00:08:58):

Enough. I want to hear enough

Speaker 2 (00:08:59):

Hear your thoughts.

Speaker 3 (00:08:59):

Fair enough. Look, here's the deal about working in a union room. There's a schedule. If you cannot be within the schedule, then number one, you suck. And then number two, that's your problem. But all the same people that probably complain about working in union rooms are also the same people that put up memes about living wages and keeping work hours to 20 hours a week. You know what I mean? These are all the same people that complain about that. But the reality is, is that when you go into a union room, you are well aware of your load in time. You are well aware of the fact that these people, meaning the crew, will go on break at a certain time if you don't have your act together to be able to work within those constraints. Okay, well then you suck, period. End of story. That's the reality, okay? If you are on a movie set, you're on a union movie set, honey, if you work at any venue, that's usually over a thousand capacity or even 2000 capacity. You're working in a union room and it's not that big of a deal. Just get your act together and do your job. And every,

Speaker 2 (00:10:07):

See, this is why I love you because my first experience with you was I almost felt like I came of age because before Punchy was in my life on that Oz Fest tour, I fucking, I couldn't handle these types of things like the pressure of working in a union room with my band or dealing with that kind of thing. And through doing all those off dates with you when Nile and having you cracked down on us in the friendliest way possible, it really, after that we could handle all of it with ease. And I actually started to prefer that environment because you knew everything was going to be taken care of.

Speaker 3 (00:10:59):

The idea is about, it's about predictability. One of the things that I used to do when I toured as a front of house engineer is I had this little, I still have it actually. I have this netbook that I purchased in 2009. It's this little tiny Windows seven based pc. And the reason why I bought it is because number one, nobody would want to steal it. So I could leave it in front of house and run Windows media player, and nobody would like an iPod would just quickly run with it and stick it in their pocket. Yeah,

Speaker 2 (00:11:33):

You'll have to pay someone to steal a netbook

Speaker 3 (00:11:36):

Essentially, even though a netbook does like 10,000 things more than an iPod could ever imagine doing. But anyway, I would use the exact same playlist every day. These are the songs that are played, and that's how it is. And one of the things that a lot of people would always say to me is, I can almost time my day from doors to the time that I have to be on stage just based on the song that's playing on the pa. And it might seem redundant to the people that are actually on the tour, but keep in mind that that's the first day your show's been in that room. So to them it's new, it doesn't matter. And I also was very, very clear, and it was very, very important to me to make sure that the pre-show music that played before the band was always 10 or 15 DB below what the band's sound pressure level was going to be.

(00:12:31):

Because then you would have excitement, you would have this, suddenly the band is loud and Oh, here we go. You know what I mean? No matter what goes on after that music, it's the heaviest thing they've heard in 15, 20, 30 minutes, whatever it is. And nothing is more annoying than what they call the metal dj. It's some guy that's playing some godawful ancient Dior gear song and it's just super loud and all this 4K is just screaming through the room and by the time the band goes on, it sounds like easy listening. That is the worst thing ever. And Lord love all the people that pretend to be metal DJs or whatever it is that makes you happy. But it just never worked on my tour. And when I advanced shows, I made sure that the venues knew there's not going to be any kind of metal dj. I have the music from Doors to Close, and that's it.

Speaker 2 (00:13:27):

I remember that too. I actually do remember that, and you never explained to me why you did that. That's really, really smart.

Speaker 3 (00:13:37):

Well, it's like, look, when you look at a movie, for instance, when a movie gets distributed, all the previews and everything that you see prior to the movie are planned. So it's an experience that the audience has from the second they walk into the theater to the second that they leave. So it should be the same experience from city to city. There's no reason why it needs to change. Nobody needs chaos in their lives, especially people that travel in vans or buses and live in a coffin for a living. They need a sense of normalcy because there's already too much chaos around them.

Speaker 2 (00:14:19):

And what's the one thing that can really help someone feel normalcy? It would be music. The way that you associate music with say that the same song is always playing at catering time.

Speaker 3 (00:14:34):

Yeah, exactly.

Speaker 2 (00:14:36):

Same song as playing right before you sound check and all that. That's a really, really, I guess, effective way to get people who don't pay attention to anything or read anything to, I guess subconsciously know what's going on.

Speaker 3 (00:14:52):

Yeah, they get an idea like, oh my God, Slayer, he's in the A business playing, I got 15 minutes, that kind of thing. So, oh my God, overkill is playing. We're on next. That kind of thing. So that's super important. That's super important to create that sense of normalcy throughout the day so that whatever chaotic thing comes at the bands or the crew that day, at least they don't need to worry about what's going on on the PA system. They got it, they've got it, that kind of thing.

Speaker 2 (00:15:26):

So the metal DJ is one of the most annoying things ever. Want to know something else that annoyed the piss out of me. Sure. Not just when the house music is louder than the band, but what about when the band's intro?

Speaker 3 (00:15:42):

It

Speaker 2 (00:15:43):

Sounds better than the band itself.

Speaker 3 (00:15:45):

You have this, right, exactly. The band's intro is some sort of symphonic piece with all these subs and all this wonderful frequency spectrum, and it's so beautiful and everything. And then the band kicks in and the guitar tone is 4K and up. It's all clicky kick drum, and it's all the guy's like, this shit is amazing. One of the funny things that I always like to say about death metal or extreme music or whatever is that it's the only genre of music where a singer can go during soundcheck and then turn to the monitor guy and say, yeah, that sounds great. It's fucking hilarious.

Speaker 2 (00:16:35):

Did you always find it funny? I always have.

Speaker 3 (00:16:40):

Yeah. I mean, look, I understand that they've got to hear something. They've got to hear whatever they got to hear to make them feel at ease with their sound or at ease on stage. I get it. Trust me, I can appreciate the comfort zone concept. But yeah, it's still really funny. It's funny, dude. I mean, it is funny or guitar players that feel the need to fill the entire room up with their guitar Amp, man, because that's my tone. It's like, dude, your tone sucks. Okay, your tone sucks. And the way your guitar sounds to you with your ass facing the speakers is completely different than the way your guitar tone sounds to an SM 57 half an inch away from this cone. So get over yourself. Speaking

Speaker 2 (00:17:31):

Of bad tone, metal, especially Extreme Metal isn't a style of music that sounds very good from the get go. Everything about it is just, well,

Speaker 3 (00:17:44):

It's definitely an acquired taste.

Speaker 2 (00:17:46):

It's an acquired taste. But what I mean is just it's arranged in a way that can easily take the sound off a cliff. It's not like a style of music where the bass sits in the bass and there's a keyboard here and maybe an acoustic guitar and a voice where it all just kind of takes its own space. Everything is competing with everything and it's chaotic and it's a tough type of music to make sound good. But you've done a great job of making some bands that I've heard with other sound guys sound terrible. You've managed to make them sound big and rich and musical. You definitely know how to make a very tough style of music sound great in the toughest of conditions. So let's talk about that some. First

Speaker 3 (00:18:40):

Off, first off, I would like to thank you for the compliment and your check is in the mail.

Speaker 2 (00:18:44):

Thank you. Thanks. You got my new address, right?

Speaker 3 (00:18:47):

Yes. Thank you.

Speaker 2 (00:18:48):

Okay, cool. Just making sure. Well, I mean, I know that your compliment right now about guitar players with terrible tone that want to fill up the room. You've had to deal with some of those guys. Sure. But then you turn around and somehow make them sound good in context of their whole band.

Speaker 3 (00:19:08):

Well, a lot of it has to do with gauging the size of the room. It's actually, believe it or not, easier to mix in say an open air where you're like a hundred yards away from the stage than it is to mix in a really, really small club where you're in line of sight of the four twelves or symbols are really ringing in a room or something like that. It's much easier. You can actually put things like overheads in the mix and stuff like that and actually get something out of it. So I actually found, other than the pressure of having to quickly dial in a mix, for instance, at an open air festival like vCAN or Brutal Assault or something like that where you have a 30 minute window to get your band on stage, micd up and line checked because you're on next, that kind of thing.

(00:20:04):

There's that pressure. But I found that mixing, you actually have more headroom and more, you can actually get more of an album quality thing because you're not in the direct sound path of any of the instruments individually. You're actually listening to the PA system and it's kind of mixing in a giant control room with really big fucking Ns tens, you know what I mean? Because if you're looking at it in field of view, they're about the size of what an NS 10 would look like to you if you're sitting in a convention. So they're really big speakers. And so I found that mixing in an open air and also in an open air, you have no natural acoustics to compete with whatever tone is happening. So any reverb or delay or any kind of effect that you put on in any instrument is actually you doing it and not the room.

(00:21:03):

So in that respect, it's easier. But when you're in a small club, and let's say for the sake of argument, your mixed position just happens to be in front of one of the guitar players, one of the things that I would have the Nile guys do, and they were really, really good about this, if their cabinet was aimed straight at me, I would always tell either Carl or Dallas like, Hey man, is there any way I can get you to just to pivot that thing a little bit more to the right or a little bit more to the left? Because if not, that's all I'm going to hear all night and I'm not going to put you in the mix appropriately. And they understood that concept and always complied. They were really, really good about that because they knew that I was always trying to make the experience for the crowd a much better experience than just mixing for myself. I wanted the crowd to get as much and as much of the sound system much that the sound system had to offer than suffering and hearing nothing but one tone all night, that kind of thing.

Speaker 2 (00:22:11):

And Nile, I got to say, Nile's, one of those bands that I heard sound great under you, and they're one chaotic band.

Speaker 3 (00:22:20):

Oh, sure. I mean, it's definitely everything louder than everything else, everything faster than everything else. But one of the things that I always like to do, and this is something that I always like to tell all sound guys, is that your console is a musical instrument. It really is. It's not a set it and forget it concept. It's not just, oh, I dial in the tones, I make it this loud, and then I can kind of sit back and watch. That's not the case because slower guitar leads tend to pierce through very chaotic moments, whereas very fast guitar leads tend to get jumbled up. So if you're not on top of that slider during the guitar lead and you don't know what's going on, then you're actually missing a good amount of what music is being portrayed there.

(00:23:10):

So it's really important to be constantly making adjustments to fit the arrangements of the songs so that people hear exactly what they need to hear at the right moment in time. So that set it and forget it. Audio engineer concept to me is incorrect in its approach. And generally speaking, I found that guys that do that aren't really musicians. They're not people that actually play musical instruments. They just happen to do sound. And the problem is that an audio engineer is the culmination of all the sounds that are happening on stage. And if you don't understand how an instrument is supposed to sound and where it's supposed to make noise at the right time, then you're actually missing the big picture and you're missing everything. And so is the crowd, unfortunately due to your negligence.

Speaker 2 (00:24:11):

Yeah, it was a nice byproduct

Speaker 3 (00:24:15):

Of

Speaker 2 (00:24:15):

You not knowing what the hell's going on.

Speaker 3 (00:24:17):

And this is a big drag about certain consoles that will go nameless is that they are non-musical in their approach. They're designed to be toured with, and so it becomes a particular engineer's console that he can go ahead and program Fader moves in and all that, and basically hit go as a series of cues. But when they show up at a festival and you spend most of your time staring at the console to make sure that you're doing something right, because the feel isn't of an actual mixing console, it doesn't feel musical. You spend less time looking at the band. And if you don't musically know what's happening, if you haven't already memorized the band's arrangements, then you're going to miss cues. You're going to miss cue because you can't stare at the band while you're doing your job. You become more of a visual audio engineer than an audio engineer that gets to look at the band, if you will. So I'm not going to name those particular consoles just in case they sponsor you.

Speaker 2 (00:25:33):

I appreciate that. I guess speaking of knowing the music, is that something that you would learn on tour or would you learn it before a tour?

Speaker 3 (00:25:43):

Well, if I ever worked with a band that I'd never had an opportunity to mix, I at least want to get their set list and if anything, learn the songs that they plan on doing so that I can be as familiar as I can before I get into show one. Usually by show five, I've got it memorized. I have a pretty decent memory when it comes to music. So by the fifth show of a tour, I pretty much have a good set routine as to what's going to happen where and why. But if it's something like a sight unseen kind of thing, then I'm like, oh boy, who's going to do what? Oh my God, who's taking this solo? And oh, that kind of thing. That can get a little harrowing. But yeah, you always try to do your research, try to do your research as much as you possibly can before you get there. It's like anything else. If you were in college or high school or whatever, and you're suddenly going to take this test without ever reading the book, you're probably going to fail the first time you do it

Speaker 2 (00:26:47):

Unless you luck out,

Speaker 3 (00:26:49):

Unless you happen to luck out and be a natural at something. There were some really kind of interesting moments. One of 'em, I got a phone call, I guess it was, I'm going to say 2013 or something like that. I got a phone call from Overkill, right, Didi? He says, yeah, hey, we're going down to South America to play this show in Columbia, which is called Rock Park, rock Out, Barque Rock Out Park is this festival that's like three days long, and each day there's like a quarter of a million people there. And on top of that, it gets broadcast live simulcast on the national television station.

Speaker 2 (00:27:34):

Real quick, isn't it funny how people in the US here couldn't even fathom what 250,000 people at a show is? And yet bands like Overkill who pull one to two to 300 people here will do that in South America.

Speaker 3 (00:27:56):

That's pretty amazing. Yeah, exactly. It's insane.

(00:27:58):

Exactly. And they're headlining this particular show, okay, they're the headliners for the metal night. This particular festival is split up into different nights. There's a rock night where your typical ever clears and that kind of thing would play. And then there's a metal night where you have this mixture of metal bands from Latin America, Europe and North America. Then you have this kind of folky kind of thing that happens on night three, like Latin music and folky music, that kind of thing. That happens on night three. So in the middle night, and not only that, but you don't fly down there with any backline or anything like that. You're using all local backline. You might be lucky enough to get your own drum set, but you're going to get that drum set, maybe two or three bands before you play to get it set up in time and all that.

(00:28:52):

You'll get your own riser, they'll roll it into position, and then whatever amps are on stage, you may get your choice of head or whatever, but you better have somebody with you that knows what the heck they're doing or you're probably going to fail. But anyway, I happen to, I happen to have been an Overkill fan. I listened to Overkill when I was in high school and songs like Elimination and Skull Crusher and stuff like that. I just love those songs. So I get this phone call and they said, okay, yeah, we're playing down there and our normal engineer can't make it. Can you do it? We know you did the festival last year with Morbid Angel, and we know that you know the situation, so can you do it? And I'm like, absolutely. Sure, yeah. Are you kidding? I'd love to. So keep in mind, I'd never mixed this band before in my life.

(00:29:47):

And not only have I not mixed this band, but the mixed position for this particular festival is not center. It's to the right or the stage left side of the PA system. So you're not even in line of side of the pa. You are mixing the band on Nearfield monitors outside on a platform like 30 feet up, 40 feet up. That's weird. It's the weirdest thing. You're not actually in line of side of the PA system. So in order to get an idea of what the PA is going to sound like, you kind of have to walk the festival, listen to what the band sounds like, kind of get a mental picture of it, and then go climb this tower and go take a listen to what that engineer is hearing.

(00:30:36):

And then when it comes time to do your show, right, then you got to kind of remember that difference and try to match it as good as possible. Now, luckily, this particular systems engineer that built that PA system had it pretty much on the ball. It was pretty close. It actually sounded like a very small version of the PA that's blasting to my left. So if you can make it sound good in the near fields, then the PA sounds good. And so far all the bootleg recordings that I've seen of people in the audience, a couple football fields back, it sounds okay, sounds great. On a phone, on a phone, you know what I mean? That kind of thing. So I guess I did that. As long as

Speaker 2 (00:31:20):

It sounds great on a phone,

Speaker 3 (00:31:21):

You're right, as long as it sounds good on the phone, but no pressure, you've never mixed the band before. It's only in front of a quarter million people and a live broadcast on television. Okay, dude, no soundcheck, no pressure, go,

Speaker 2 (00:31:36):

And you have to do it in a sniper tower,

Speaker 3 (00:31:38):

And I have to do it in a sniper tower. And keeping in mind, this particular festival is put on by the government of Columbia. So is a response to the old Pablo Escobar thing, at least this is what I was told. Maybe I'm wrong, but I was told that basically during the era of Pablo Escobar, he had such a very large employment base, if you will, employee base. And he would put on these concerts, like open air festivals and stuff like that. So when they eliminated him from the equation, there was this kind of emptiness void that needed to be filled. So the government put on this festival, this three day long festival to kind of fill that void. And it's a dry festival, so there's no alcohol anywhere on the grounds. You can't even bring alcohol into the backstage. They frisk you and they search the bus.

Speaker 2 (00:32:38):

That seems interesting. That seems like that festival might have to be an acquired taste for some people.

Speaker 3 (00:32:46):

No, there's a quarter of a million people that show up and have a great time and have an awesome time. I mean, they love it mean how often do they get a chance to see this kind of thing and be part of this size? I just

Speaker 2 (00:33:01):

Can't imagine a festival that size with no alcohol. That's incredible.

Speaker 3 (00:33:05):

No alcohol and giant tanks and military vehicles at the front gates, so ain't no terrorist either. So

Speaker 2 (00:33:20):

All in all, it seems like a pretty good time if you can get the sound right.

Speaker 3 (00:33:24):

Yeah, of course. I mean, again, there's a lot of pressure because also your board mix is the mix that's going out over on the television station. So yeah, not only does it need to sound good outside, but it needs to sound good in headphones too, because that board makes is what the rest of the country is seeing. Do you like that kind of pressure? Why not?

Speaker 2 (00:33:48):

Some people buckle under it. I think they're in the wrong. Why not? They're in the wrong business. Fair enough. But have you always been okay with it? Is this something you had to, I guess, learn how to deal with? Does it just come naturally to you?

Speaker 3 (00:34:04):

Well, nothing comes naturally. I mean, I had my puckering moments, don't get me wrong. There were moments where when it's the first time you're mixing a giant festival and you better hope that you know what you're doing. And at that point, you just kind of close your eyes and just kind of do what you do, do what you do, and hope your skill works in your favor. Trust me, there's an old adage. Everybody knows two things in their life, what their asshole supposedly smells like and sound. So if there's a problem, someone in Germany will let you know that you're doing it wrong.

Speaker 2 (00:34:48):

It's true. That is absolutely true. They will let you know.

Speaker 3 (00:34:51):

Oh yeah. And it's the funniest thing because they'll give you these strange criticisms like, Hey, the hi hat's too quiet. And you're like, dude, shut up. You know what I mean? Get the hell out of here. You know what I mean? They'll do it in the middle of the song while you're doing your job. Hey, turn up the high hat. You're like, dude, shut up, man. Get out of here. Go get drunk or something. You know what I mean? Shut up. If that's what you're worried about, then I guess I'm doing all right. So yeah, it's pretty amusing the way fans. And then you also have those very gracious fans that come up to you at the end of the show, and thank you for doing a good job. And I always like to say that the sound guy is the last guy to know that he's deaf.

Speaker 2 (00:35:38):

One of my funniest moments was sound checking in Poland once and on this particular show, we had to work with the house guy. I think the guy that we had on tour was sick or something. So we're working with the house guy, he's sound checking us, he's being real cold and one word answers. And he spoke good English. It wasn't a language barrier thing. And so we go through the soundcheck very, very mechanically. We get to the end and he has barely said anything to us. They're like, what do you think? How's it sound out there? And the response was, for me, this is shit. Thanks. Thank you. Thanks dude. For me, this is shit. Thanks.

Speaker 3 (00:36:29):

There was this guy, I think his name was Christophe, right? He was a merchandiser in Europe. And my early years of touring with Morbid back in the early nineties, early to mid nineties, this guy just always seemed to be there. And he was a smart dude. He spoke nine languages or 10 languages and probably should have been working at the UN or something like that. Something a little bit more meaningful than selling t-shirts at a heavy metal show in front of 400 people. Not that there's, okay, let me stop myself. Not that there's anything wrong with selling merchandise offense. I'm not offending anybody here. Okay? But when you speak 10 languages, dude, and that's the best you got going on, then maybe there's something else wrong with his personality. Well, anyway, one of the things that he would do is he would go up to you, whoever you were as an artist, not to me as a sound, but to the artists and tell them straight up like, yes, I loved the first song from your demo, but the rest is shit. It was the, I love that it was the guy who was the best. You know what I mean? The rest is shit.

Speaker 2 (00:37:43):

I don't know why when you're over there, those people coming up to you and telling you that is just the funniest thing ever.

Speaker 1 (00:37:51):

Whereas

Speaker 2 (00:37:51):

Sometimes over here, people coming up like that, they're so unwelcome. It's like, just get the fuck out of this backstage who asked you your opinion? Yeah,

Speaker 3 (00:38:01):

No, he cares.

Speaker 2 (00:38:02):

Yeah. Over there you could have some guy spitting in your face, drunk all over you, hugging you, totally violating your personal space, telling you how bad everything you did is. And it's okay because it's funny.

Speaker 3 (00:38:18):

It's okay because you're actually over there and it's a different animal when you're over there. You can't be ashamed of foreigners, but you can be ashamed of your own people. So it's easy to be ashamed of an American telling you, you suck, dude. You suck. Then some guy from Latvia going, yes, I think you suck. You suck.

Speaker 2 (00:38:48):

I loved it. So, alright, so speaking, this is a good time to pivot. Let's talk about tour managing, because you taught me a whole hell of a lot about surviving on the road, and I'd say that you're about as serious of a tour manager as you are as a sound guy. You basically helped my band that literally didn't know what the fuck we were doing, get our shit together. And you were nice about it too. But I'm sure that people listening to this can guess that you run a pretty tight ship.

Speaker 3 (00:39:25):

Sure.

Speaker 2 (00:39:26):

And that really, really helped. How did you get into tour managing? Do you enjoy it? Do you ever see that happening again? And let's just talk a little bit about it. I want to get into

Speaker 3 (00:39:37):

It. Sure. The long and the short of how I got into tour managing was I was on several tours with both good and bad tour managers, effectual and ineffectual tour managers, sober and drunk or high tour managers. And this one particular time I was out with this goth band called Christian Death.

Speaker 2 (00:40:00):

I remember them.

Speaker 3 (00:40:01):

Okay. We were in Europe and we had this tour manager who was a nice guy, but he was just kind of ineffectual. He wasn't,

Speaker 2 (00:40:10):

And you were doing a sound?

Speaker 3 (00:40:12):

I was actually, my job description was guitar tech slash keyboard player in the band. Okay, okay. Because they had about four or five songs that had, this is the days before playing to a track. You know what I mean? This predates a real computer or anything. This is like 1994. Okay. So this predates the computer that it would've taken to do tracks would've been like a giant tower of some kind. And there wasn't really, pro tools didn't even exist. It was sound tools and that kind of thing. It predates a DATs, even to give you an idea, they had a few songs that had keyboard parts and I could play keyboards good enough to edit. So you liked that good enough to edit.

(00:41:03):

So I would tune guitars and in between guitar changes, I had a few songs or I had to play keyboards. And we had this tour manager guy. He was a nice guy, whatever, but he just really, he never dotted i's and crossed. He was always that kind of, he left things undone. And then I just wound up picking up a lot of slack. And then finally the next tour valor, he's like the Eddie Van Halen of Christian Death. He's like the leader of the band. He just said, Hey man, could you tour manage? And actually earlier in that tour, we had an engineer that was going to show up on the tour about four or five days into the tour, he was crossing over another tour that he was doing. And so I went out front of house and got basic tones for the house sound guy to just kind of push faders on. And valor thought that I did a good job doing that. So actually Valor from Christian Death gave me my first shot at sound engineer and tour manager and the tour that followed that tour where I was guitar teching and playing keyboards. He had actually bought an A black faced a DA and started playing the tracks on the following tour. So they didn't need a keyboard player anymore.

(00:42:28):

And so they just had a guitar tech at that point on

Speaker 2 (00:42:31):

The tour. Lo and behold, the Monster was born.

Speaker 3 (00:42:33):

The Monster was born. So he actually gave me my first shot. And then when Formulas fatal to the flesh, first toured in 98, I was given the job of lighting guy and Tour manager because they had, as a front of house engineer, a guy named George Jarius, who was the sound engineer for Acts like Blue Oyster Cult and Docking and stuff like that. He had done that in the eighties. And so he was doing, oh, and he also did Anthrax. That was another one of his big bands that he did in the eighties and early nineties. So Morbid Angel hired him to be the sound engineer, and then he did the American tour. But then he had a bout with, he had a tumor in his stomach that he was able to have removed, but he couldn't do the American tour. He did the European tour, but he couldn't do the American tour. So then Gunter, the band's manager said, okay, well dude, do you want to mix Morbid? You're the only person I know of that's actually been with the band for several years, knows the music, do you want to do it? And I said, yes, I do. And so I wound up mixing Morbid at that point, and I pretty much was their audio engineer from 1998 up until 2014.

Speaker 2 (00:43:55):

God damn. So did you tour manage them as well?

Speaker 3 (00:43:58):

Yes, I did both jobs. It was harrowing to say the least, but only because they have very, very hectic tour schedules and they'll do back to back. They'll go to Europe and then they'll fly home for three days and then we go to Japan and Australia and that kind of thing. It was just a lot of stuff to go on. And I basically played the role of fifth Beatle for over 20 years of the band, and I did everything I could. I worked on two of their records. I even did a documentary for the band, the Tales of the Sikh one, that was the companion to Bless of the Sikh when they did the 20th anniversary of that. I believe it was 20th anniversary or something like that. 10th anniversary.

Speaker 2 (00:44:45):

I watched that six months ago.

Speaker 3 (00:44:48):

Oh, you did?

Speaker 2 (00:44:49):

Yeah. For some reason. I don't know, I just got curious about the old school death metal production and because I remember at the time, people now things have changed, but at the time people were like, it's so slick. How do they do it? It's so processed and all this stuff. I wanted to just, I don't know. I just wanted to get a look into that world. And that was one of the only looks you could find.

Speaker 3 (00:45:18):

Yeah. One of the things that I made it a point was I went a little nerdy when I was interviewing Tom Morris, and I started asking him questions that your typical metal interviewer guy wouldn't ask. Like, oh dude, did they wear leather? None of that stuff. You know what I mean? I asked him like, dude, how did they wear leather? How with tape machines back in the day, because there was no sound tools, there was none of that stuff. How with tape machines did you do sound replacements? How was that possible? And he explained the whole technique to me that it was kind of voodoo and how they used to do it back then. But also album budgets were 90, a hundred thousand dollars. It was not unusual to have these big album budgets because at the same time, record labels were actually selling records. And nowadays it's nearly impossible to get people to buy pieces of plastic, let alone buy bits. So is difficult for record labels and artists alike to make money as recording artists.

Speaker 2 (00:46:31):

At that point, I guess you could take the time to actually replace your drums via tape and midi.

Speaker 3 (00:46:41):

Yeah. Well, I dunno if you remember how Tom Morris explained it, but basically they would sample a hit of Pete's snare drum or Pete's Kick or one of his Tom's or whatever into this TC Electronics digital delay that actually was capable of That's

Speaker 2 (00:46:58):

Right. Yeah, that's right.

Speaker 3 (00:46:59):

It was capable of making a one second sample, and then they would take the signal out of the erase head, which was the last head and line of the tape machine. They would take the signal out of the erase head and trigger the sample on the TC native, a TC electronics device, and then set the dwell. There was a knob where you could set the dwell so that it would actually sync up to the actual hit and then hit record on another track on the tape, and then just record that

Speaker 2 (00:47:31):

Fucking voodoo man,

Speaker 3 (00:47:34):

The stuff they had

Speaker 2 (00:47:35):

To go through. Unbelievable.

Speaker 3 (00:47:37):

And that's after, of course, they took razor blades to all the various takes and made dos Uber take, and then they could do this particular process

Speaker 2 (00:47:47):

Changed so much. But just out of curiosity, were you ever in the military or did you have military in your family?

Speaker 3 (00:47:55):

My sister. But here's the long story. My sister was in the US Navy. I had every intention of going into the US Navy. And actually when I was in high school, I graduated in 1989, and when I took a test called the As vva, which is the armed services vocational aptitude battery. And I'm not sure if they still give that test anymore to high schoolers, but they did when I was in high school and out of 1400 questions, I missed two. And so I was getting phone calls and left from every branch of the military service to try to get me in.

(00:48:33):

I had asthma when I was a very young child. My last asthma attack was I think when I was three or four. And at the time, we were not at war with anybody. So the need for military personnel was very, very little. It was very small. There was not an awful lot of demand for military people. So you had to pass the physical aspect of it first, and then all the other stuff would just kind of fall into play. So even though I had all these really crazy high school scores or anything, I didn't on paper pass the physical test needed. I had a history of asthma, and I could have had what was known as a special permission from my congressman, but then I just would've been that guy in the barracks that got the special permission from the congressman. And I ever want to be anybody's special, anything. You know what I mean? I wanted to earn everything that I ever got. And so I didn't go into the military, but my sister answered the call and she wound up going into the US Navy and later on to the Office of Naval Intelligence and then went to the JAG Corps and that kind of thing. And she actually still works for the US government, but she lives in dc.

Speaker 2 (00:49:59):

Well, it's interesting that you say that because I feel like from the way that you run things, it seems like that's either in your background or almost in your background or in the family or something.

Speaker 3 (00:50:16):

Well, I believe it or not, and I dunno if you ever knew this about me, but I come from a theater background. Okay.

Speaker 2 (00:50:24):

Oh, I knew that After you started, after I watched you do karaoke in Japan, I knew about the theater background,

Speaker 3 (00:50:33):

Right? So I grew up in an environment where there was rehearsals and for instance, I would come home from school and I didn't go out and play football with friends or anything like that. I was home from school, I had homework, and then I had to go to rehearsals. And by the time I was age 12, I was stage managing. My father had this theater company, not a theater, but a theatrical company that would go into theaters and put on productions. So I was stage managing his shows in union theaters at age 12, because by the time we actually got out of rehearsals and into production at the theater itself, I had already memorized the script and I knew all the set changes and everything by heart. So it was just a question of putting on a headset, and these people would take my commands, well, I guess commands is the right word.

Speaker 2 (00:51:30):

Commands command

Speaker 3 (00:51:31):

Is a good word, commands is the right word. But these people would follow my lead and they would do what I said. And these were older guys and unionized guys. And when it came time for me to actually go for my own union card, pretty much everybody knew me. And I got almost practically unanimous. Yes. Across the entire local, because by the time I'd actually gone for that, I already been working with these people over 20 years.

Speaker 2 (00:52:03):

So the whole discipline of schedules and doing everything on time and getting it right was just there from a young age.

Speaker 3 (00:52:13):

That's right. I've never understood the idea of being late. I've never understood the idea of making people wait. I mean, it's happened. I'm not perfect by any stretch of the imagination. I mean, everybody makes mistakes, but I don't like it. Yeah.

Speaker 2 (00:52:29):

Alright, let's see if we can get into a time capsule. Do you remember 10 years ago sitting in the back lounge of a bus explaining to me and my band what we needed to understand before going to Japan? Remember we had that pre-tour meeting where you're like, you're going to have to get this and this together on your IDs, and these are the rules like you can and can't do this. And Paul McCartney this and Paul McCartney's that. Do you remember this

Speaker 3 (00:53:05):

At all? Yeah. I pretty much told you straight up that there is a zero tolerance for dope or anything like that in Japan. I mean,

Speaker 2 (00:53:12):

Yeah, you laid everything down, but you laid it down from passport regulations to cultural norms to how we're expected to behave at the venue to Paul McCartney's weed thing. I was wondering if you could walk us through that again,

Speaker 3 (00:53:30):

Just

Speaker 2 (00:53:30):

So that

Speaker 3 (00:53:30):

Okay, well, I'm going to have to set my way back machine here. But I know that I was, one of the things that, and this is to anybody that's going to go get a visa to go to Japan, understand that the Japanese are a very tolerant culture, but at the same time, they're sticklers for detail and they're sticklers for being on time and being respectful. Okay? They will show you all the respect in the world, but if you don't give it back, then you're probably never going back. And that's an important thing to remember. So if they tell you that you need to have your visa ready by this certain date and that these documents better be in your visa packet and that, have you ever been arrested? Don't lie. Have you ever been arrested? If so, where? When give details, you think you may be slick and cool and all that, but you're not going to get one over on the Japanese, that's for sure. They're very, very detail oriented, and it was important. I mean, you guys, for the most part, just so you understand it, I liked your band. There's very few bands that I actually liked. Okay. So I liked working for da, I thought that I loved the songs. I mean, matter of fact, DA was one of those, the two records that you had were amongst my everyday playlist for tours. Oh,

Speaker 2 (00:55:00):

That's

Speaker 3 (00:55:01):

Cool. So death music has actually been played on every continent I've ever worked on since 2007 and beyond. How does that sound?

Speaker 2 (00:55:09):

Nice.

Speaker 3 (00:55:09):

Okay. Sounds

Speaker 2 (00:55:10):

Good.

Speaker 3 (00:55:10):

Yeah. And on top, and I'm not just buttering your muffin here, but I mean, the production sounded great, but the songs also fit the crowd. They fit the crowd. I mean, they even fit, when I was out with Symphony X, they were part of the playlist for Symphony X. It even fit that crowd. I never had anybody, even though it's a lot of screaming in the vocals or whatever, but that didn't matter. That kind of thing. It fit. So anyway, I liked your band, so I wanted to see your band actually do well and succeed. So I tried to give you as much information that I could that would actually benefit you. And I remember there was a couple of little tiny things that were a little strange with some of the Visa applications. I don't want to go into detail. Can I go into details or No, I shouldn't go into details.

Speaker 2 (00:55:59):

You just don't name names.

Speaker 3 (00:56:00):

Okay. Yeah. There has been some arrests, some people had some issues with the law, and yes,

Speaker 2 (00:56:08):

They did. They

Speaker 3 (00:56:09):

Had some issues with the law, but because it was reported and it was truthful and factual on the Visa application, it went through and you guys wound up going, I remember we got the Visas back pretty quickly actually. I remember while we were out on Oz Fest, we did all the paperwork because y'all can tell you Oz Fest 2007, you started the day, started at nine o'clock in the morning. The first band was on at 11:00 AM you played for 20 minutes, and then you had two minutes to or unload your show from the stage and two minutes to get your show on the stage and start. And that was, you had literally

Speaker 2 (00:56:58):

Five

Speaker 3 (00:56:58):

Minutes in between. And then of course you had, what was the name of that one DJ dude that kept bringing you out on stage? What was his name? Do you remember his name?

Speaker 2 (00:57:06):

Something Dave?

Speaker 3 (00:57:07):

Yeah. He was like, who wants to drink Jager? Who wants to drink Jager? And then, oh yeah, heck guy. And then there was you on stage doing shots of Jagermeister with this freaking guy. I think you guys were sponsored at the time, right? Weren't you sponsored?

Speaker 2 (00:57:23):

Yeah. That's officially or unofficially. They gave us a lot.

Speaker 3 (00:57:27):

Who wants to drink some Jaga? So getting you guys on stage and getting you playing also included that. Who wants to drink some Yaga moment with this guy? So we actually wound up getting you guys on stage about three and a half minutes or something like that. Then there was that stupid little break. And on top of that, Oz Fest did not have a set schedule. There were only three bands that actually went on at a set time every day. And that was Behemoth Devil Driver and Hate Breed. Everybody else that was on the tour was on this revolving schedule. You were either going on first or second or third or fourth or fifth, and then the next day you're going on second third. In other words, there was no, you couldn't plan your day. You just knew that it was going to suck from 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM Am I right? Am I right? It was going to be hot and shitty, and it

Speaker 2 (00:58:27):

Was going to suck. You're absolutely right. There's no rhyme or reason to it. You just had to go with it and you literally did have five minutes, five minutes, five minutes. Five minutes, or you get in trouble.

Speaker 3 (00:58:40):

Yeah, two minutes up. Two minutes down. And if you went on late, a well, asshole, I guess you're cutting a song

Speaker 2 (00:58:47):

Or better find a shorter song to play instead, or

Speaker 3 (00:58:49):

Find a shorter song to play of Lay. But yeah, it was funny because Nile, they're famous for having these 20 minute long songs. They played four songs. That was it. Nile played four songs every day.

Speaker 2 (00:59:04):

Yeah, that was ridiculous. But we did, we got all the documents done somehow while on that tour.

Speaker 3 (00:59:10):

That's right. I did remember that. And this is also 2007 where this idea of wifi and all that nonsense that just really didn't exist. So we were lucky enough, death and Nile were doing off dates between Oz Fest. So every two shows we would have an off date. So that off date would allow us to be in a building that would either have one cable that had internet on the other side of it, or maybe an internet router that had wifi, which is amazing in 2007. So yeah, that was difficult to get all that together. But we did. We got it all together. We got the paperwork sent in, we got all of our passports and paperwork back. Everybody did what they were supposed to do. And then when you're in Japan, okay, let's say for the sake of art, you're at the hotel and they tell you, okay, lobby call is at 8:00 AM We leave the lobby at 8:02 AM okay, at 7 59 in 30 seconds, the car will pull up to the front of the hotel to pick you up, and you'd better be in that van by 8:02 AM because at 8:07 AM the train leaves for the train, leaves for your next show.

(01:00:31):

And if you're not on it, you miss it. And now a lot of money is wasted and you start wasting the Japanese money. And guess who's not coming back to Japan? There's a band that wasted a lot of Japanese money that's probably never going back to Japan. That will remain nameless.

Speaker 2 (01:00:52):

Oh, the one that didn't show up,

Speaker 3 (01:00:54):

The one that didn't show up and then put something on their MySpace about how they couldn't get their visas in time. It's like what?

Speaker 2 (01:01:04):

I mean, they didn't have punchy helping them.

Speaker 3 (01:01:06):

That's part of it. Right.

Speaker 2 (01:01:08):

Well, that was kind of what I was getting at with going through that is that without having you to help us, we would've never gotten in that shit together because no one would've laid it out for us just point by point by point what you have to do, how you have to go about it. And it would've been a disorganized disaster. And who knows if it would've happened.

Speaker 3 (01:01:30):

Yeah. Well, if I didn't like you, I would've just left it to the wolves.

Speaker 2 (01:01:35):

I mean, you also told us a lot about how behave there and how to not get arrested.

Speaker 3 (01:01:40):

And for the most part, everybody behaved really. I mean, there was no problems. And everybody got along. We were out with Zyklon Zyklon was the headlining band, and everybody got along. There was no problems. I remember because the one particular band didn't show up, you guys had to play an extended set and so did Zyklon. Everybody had to extend their set by 10 or 15 minutes to try to make up time because of the showtimes that were scheduled. And everybody did a great job. It was a really enjoyable experience. And oddly enough, while I was there with you guys, a band dropped out of the Loud Park Festival and I was able to sign the deal for Nile to play the Loud Park Festival, and I happened to have all of their Visa information with me in my laptop. So I was able to file all the Visa paperwork while I was in Japan. And two weeks later we were back in Japan. I was back in Japan with Nile doing loud Park. So it just goes to show preparedness and information and knowing what to do at the right time does get things accomplished. So there you go,

Speaker 2 (01:03:09):

Especially in an industry that's generally chaotic, those who have their shit together prevail

Speaker 3 (01:03:19):

And loaded with people that I don't know how they get jobs. I got to tell you, man, working at the theater, I work with a production manager and he lets me know about all the tour managers that just don't return emails, don't return phone calls about advances and that kind of thing, and it boggles my imagination. How do these people get work and how do they stay employed? Who's cock are they sucking? I mean, for lack of a better term, of course, but how is that possible? Because I could never imagine running my show that way. I mean, even before cell phones and before the internet and stuff like that, man, I made it a point to try to get most of my tour advanced before I even left for the tour, so that I had a little tour itinerary book that was printed out of a dot matrix printer and a Xerox machine. You know what I mean? This is just how it was and going to payphones and calling venues because the cell phone just really didn't exist or it did, but it was so expensive that no tour budget could ever afford to have one out there unless you were a Mr. Cool guy and you were playing big rooms. But I was doing clubs at the time, and you try to do it as gorilla as you can. So I don't get it how some of these people stay employed. I really don't.

Speaker 2 (01:04:55):

Well, I feel like there's very little experience when it comes to being organized and professional in a lot of the music industry, so they don't even know what's wrong because they don't have anything to compare it against. Once you have the experience of working with someone like you, or if you come from a business background or a military background, something like that, then you'll know that it's fucked up. But you don't have that if you don't have someone to show you or some sort of good background where that would be instilled in you, how would you know?

Speaker 3 (01:05:36):

No. Fair enough. Fair enough. But

Speaker 2 (01:05:39):

Which is a problem.

Speaker 3 (01:05:41):

But if you get to a building and everything's a bunch of chaos, then there's only one person to point at and that's your management. That's your term manager. He's the guy that's in charge of controlling the chaos. That's his gig. That's what he does. His primary function is controlling the chaos. And if you're an artist that's making a tour manager's life so impossible that he can't control the chaos for you, then you are the asshole.

Speaker 2 (01:06:06):

How many of those have you dealt with?

Speaker 3 (01:06:08):

Well, everybody has their moments. Everybody has their moments of coolness. Everybody has their moments of like, dude, I hate you. I have been very, very fortunate that either I have gained the respect of the people that I'm working for to the point where they don't make my life difficult or I'm so organized that they have nothing to complain about. One of the two, one of the two.

Speaker 2 (01:06:40):

That's pretty great. So hey, I've got some questions here from our audience.

Speaker 3 (01:06:45):

Fire away. Damn you.

Speaker 2 (01:06:46):

Awesome. We've got quite a few, so I want to get into them and these are good. So I'm probably going to butt in on your answers and talk to you about some of them. But here's one from Sasha Riesling, which is what are your most favorite and least favorite things about touring in Europe? Can I just say something? Yeah, sure. Sweaty cheese. That's my least favorite part. God, the sweaty cheese, guys, get it together. Alright, what do you say about this?

Speaker 3 (01:07:16):

Well, sweaty meat and sweaty cheese is not just Europe, but it's a's a phenomenon that's phenomenon of this worldwide sweaty meat and sweaty cheese. And if anybody doesn't understand what that means, that's cheese and meat, like a meat deli tray or whatever that's put out at 11:00 AM and by 1 32 o'clock in the afternoon, since it's not refrigerated, it has sweat on it. So that's what that is. Okay. My favorite thing about touring about Europe is number one, I'm a history buff. So anytime I am anywhere in Europe, I want to know as much as I can about the city that I'm in and its history and it's good and it's bad. So that's already the first thing is when you're in Europe, you're standing in a plaza that's five or 600 years old or you're looking at a building, that's when you're in Italy and you're looking at a building that's 2000 years old or something that predates Christ, even though you don't believe in a may. But I believe he existed. No, I know. I know, I know. I get it. I'm just playing with you. I'm just playing with you. Yo, take it easy. God bless. Take it easy, man. No, I mean, to me that's the best part about Europe. And then on top of it, it actually took me a couple of years of touring Europe to appreciate it.

Speaker 2 (01:08:50):

Dude,

Speaker 3 (01:08:51):

What

Speaker 2 (01:08:52):

Just made me laugh. No, sorry. Sorry. Go on. It took you a few years to appreciate,

Speaker 3 (01:08:57):

Appreciate it because at first when I went over there, the only thing I could see before me was all the inconveniences. I mean make, there was some running jokes or some snits that I came up with to kind of describe certain things in Europe, like the Inconvenience store, which is the convenience store that has nothing in it that you actually want to buy and you have to buy it through a window because it's after midnight and they don't let you in. So I call that the inconvenience store. And then of course it was the room temperature, which was this box that sat in your dressing room and it didn't matter how hot or how cold it was in the room, your beverages were always a comfortable 72 degrees Fahrenheit.

(01:09:41):

And then it was the squat and plop, which is the toilet that has no seat and no bowl. It's a hole in the ground with two places to put your feet and two handles that acted almost like the beginning or the starting point of a ski jumper. You know what I mean? So I always thought about, to me, the first couple of years I was in Europe, that was what it was to me. It was just a series of inconveniences and I don't understand why they do things this way and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And then it actually took being on a tour where I wasn't on a tour bus and in a van to really appreciate what Europe was all about because now you could go off the beaten path. You didn't see Europe for just the venues and the coffin that you slept in at night.

(01:10:37):

You saw Europe as it's driving by you, as you're part of it, if you're even driving. I actually had an opportunity to drive while I was there and on my first van tour. And you gain a different perspective of it. And when you actually take the time to talk to people and get a feel for you start to realize how similar you actually are, even though you may or may not share a language or may or may not share a culture or even values, but everybody for the most part is a human being and they all have the same relative desires and needs. So to me, I wound up loving being in Europe for all of us little quirks and stuff that's a little different, like being closed after 5:00 PM and that kind of stuff. All those little quirks didn't mean as much again because now I knew the rules and I knew how to deal with it and I knew how to get around it, but I also learned to love those idiosyncrasies.

(01:11:45):

I mean, I am married a European woman and her old world values here in America to me represent a little bit of what I miss about Europe. So I mean, sure it is like anything else. I mean there's stuff you can hate. The buses are different. They're not as comfortable, but there are comfortable versions and they are getting better, but it's just different. It's just a different animal. And that's good. That's good because learning about other cultures and being part of those other cultures remind you of where you came from. At least hopefully it should remind you of where you came from. And if you can't see that, then you might be too stupid for this business.

Speaker 2 (01:12:38):

I agree. So here's one from Nick, which is what are your top tips for a band about to go on their first major tour? This one happens to be an Australian interstate tour. So eight hours in a van between major cities.

Speaker 3 (01:12:52):

The first thing I can tell anybody that's traveling by road, no matter where you are, Europe, America, Australia, South Africa, whatever, if you want to take the roads in South Africa. But anyway, you know what?

Speaker 2 (01:13:06):

I'll pass on that one.

Speaker 3 (01:13:08):

Get your ass out of bed and get on the road and be at the next venue on time. That's the reality. You're always better off being 20, 30, an hour minute, 60 minutes late or early, pardon me, than you are being late because then you're just going to be those guys. And all anybody will remember is the fact that you showed up late, and so it might suck. You're going to be tired. I'm going to tell you right now, man, if you're in a van and you're traveling eight hours a day and playing, you're going to be real tired when it's all said and done. But you know what? You'll get over it. You go home, sleep for a couple days, whatever, you get over it. Big deal. Big deal. It's not that bad, okay? At the end of the day, it's not that bad. You're out there playing your music. How bad could it possibly be?

Speaker 2 (01:14:03):

I agree. I also say make sure you know where the gas stations are.

Speaker 3 (01:14:08):

Oh yeah. Well, nowadays with the Google and the Siri and all that shit, there's no reason to not know where anything is. Period.

Speaker 2 (01:14:19):

No reason. But I'm sure bands will figure one out.

Speaker 3 (01:14:23):

Yeah, well, I mean plan ahead. I mean, the best thing to do is just plan ahead. And if someone in your group is being a stickler for time or being like a, Hey man, we need to do this or whatever. Don't give that guy grief, man. He's just has your best interests at heart and that guy is going to save your tookus. He's going to save your ass. He's going to make your band seem the most professional thing. Yet it's not.

Speaker 2 (01:14:52):

It is good of you to say that those are the guys in the band that usually get the most hate. But you're right, being late to a venue, that's the shit that people remember.

Speaker 3 (01:15:02):

Oh yeah.

Speaker 2 (01:15:05):

The dude in the band stressing out over it is the dude who understands that it's important that you have your shit together. I would also say that if you're going to be doing eight hours, that you guys rotate drivers every three hours.

Speaker 3 (01:15:21):

Oh yeah. Road fatalities. Talk about being late to the venue. If you're dead, you're late to the venue. Sorry, a bleeding dagger through the skull couldn't be here tonight. They're dead.

Speaker 2 (01:15:35):

Yeah, and you won't get another tour after that.

Speaker 3 (01:15:38):

No. That pretty much ends your touring career.

Speaker 2 (01:15:40):

Yeah. So definitely rotate drivers and also know who's up the next day. If you guys are a band that likes to drink, make sure that you have an understood rule where the guy who's driving first shift the next day or later on that night is not drinking. And if your rotation is planned well enough, it should work out to where there's not one guy who always gets the shitty end of the stick. Like one guy who never gets to drink, or one guy who never gets to hang out, or one guy who always ends up driving first after the vent news clothes or whatever.

Speaker 3 (01:16:20):

Yeah, that's not fair. That's not fair to put everything on one guy or whatever. That's not fair. Everybody, you're all in this together. And if you don't know what that means, then watch Band of Brothers and you'll get it. Okay, there may be a sergeant or whatever, but you're all in the foxhole together and you'll all survive together if everybody works together as a team. So get it. Get it. That's the best way I could is get it. You know what I mean? Get it. It's not a joke, but get it.

Speaker 2 (01:16:54):

Alright, here's one from Liam Knot, which is did you talk to bands about doing front of a house for them or did they find you, was it through local gigs or something else?

Speaker 3 (01:17:06):

A little bit.

Speaker 2 (01:17:07):

I know you told the Christian death story.

Speaker 3 (01:17:09):

Yeah, a little bit of all the above. I mean, definitely there's bands that I was like, believe it or not, dude, you're going to laugh. A band that I've always wanted to mix is striper.

Speaker 2 (01:17:23):

You're right, I did laugh, but not because there's anything wrong with that, but just because

Speaker 3 (01:17:28):

No, no, no. You know why? Because I think they're both really awesome guitar players and I always thought that Michael Sweet was kind of like the heavy metal version of Dennis D. Young, and since I grew up listening to S Sticks as a kid, when Striper came out, I was in high school and striper came out, it's like, yeah, okay, whatever the Christian rock, whatever, blah, blah, blah, blah. But if you think they suck, try and play it. You play soldiers under command and you tell me that they suck. You know what I mean? So I always wanted to play with or mix that band live and I just never had the opportunity. It was just kind of a drag. But I always wanted to. But I did approach them. I did send them a resume and all that stuff, but they at the time were hiring people out of the Boston area, so I was just kind of not in the running.

(01:18:18):

But yeah, it's a mixture of all the above. I mean, you definitely, word of mouth helps more than anything else. And if you happen to be in a situation where you're mixing one band and then another band that happens to be on the tour with you needs an engineer, then you can pick up a few extra bucks by doing, that's how I started. That's how AAL and I knew each other was because I was already out mixing Nile. And since Doth is going to be the support band for Nile on our off dates, then they threw me a couple of bucks and I mix them on off dates and I mix them at the Oz Fest as well. So it's kind of a great way to also double dip a little bit and get a little extra money. You just have to work a little harder.

Speaker 2 (01:19:05):

Alright, here's one from Charlie, a band, which is, hello Juan. When you think of small time local bands starting its first weekend runs, mini tours, what kinds of do and don'ts come to mind specifically? What would be a good game plan for getting shows from out-of-state venues and promoters? Thanks.

Speaker 3 (01:19:28):

Okay, well the first thing you have to understand about promoters in general and club owners is that they're not in the business to showcase you. They're in the business of selling tickets or selling drinks at the bar and keeping asses in their building or getting asses to their building. So you as a local band really don't have any value per se to these people because you're not selling records or whatever. I mean, that's still, believe it or not,

Speaker 2 (01:20:06):

A metric.

Speaker 3 (01:20:07):

A metric thank you by which people say, okay, well if they're selling 10,000 units, then they're probably going to do a couple hundred people here. If you're a local band and you're looking to get out and do shows, you're going to have to get ready to put out the pocketbook and pay for your own gas and don't expect to get a bar tab and don't expect to get paid or any of that stuff because you're going basically out there to prove that you have an audience share in the market. So now if you go down, let's say, let's say you're from Florida and you're a Tampa band and you go down to Miami and you might be doing 50, 60 people at the local club in Tampa, but you go down to Miami and nobody knows who you are, then why would that club owner pay you a hundred bucks?

(01:20:59):

He pays a hundred bucks to the band that's on the package that's going to draw four or 500 people on Friday. Why would he pay you a hundred bucks? So the best advice I can give to anybody that's trying to do it is remember why you're doing it to begin with is because you like to present your art in front of people. And if you need money to present your art in front of people, then get a job and have a job. And that allows you to go out and then have money to go do that until people are willing to pay you for your art. I can give you an example going back to my dad and the theater company. The theater company was a non-for-profit organization, so all of the ticket revenue that came in from any of the productions that we put on basically went back into the cost of the production.

(01:22:01):

And my dad didn't make any money on it. He did it as a giant hobby. It was just a big hobby. It was just something to do. Now down the road, there were these actual paying gigs where they're doing concerts or whatever at the state fair, and he puts together a band and a few singers and dancers or whatever, and there's a contract that allows for salaries to be paid because there's not really any overhead. But when there's a gaggle of overhead and you're doing Broadway shows and you have to pay royalties and you have union musicians, union stage hands, there's a lot of hands out. There's no money left over. And so it's doing it because you want to. So if you're in a band and you're expecting to make money, then you're probably doing the wrong thing. You're doing this,

Speaker 2 (01:22:46):

I'm sorry, you do need to look at it like a hobby, at least for the first few years. I can tell you that with my band right around the time that we stopped about four years into being signed was when we were finally starting to get past breaking even on tours. We were finally getting to the point where it was starting to round the corner and that's cool and all we had to stop for other reasons. But you do kind of need to look at it like a hobby and not in a derogatory way, more just in a, you had to pay more into your passion than your passion will pay out to you.

Speaker 3 (01:23:28):