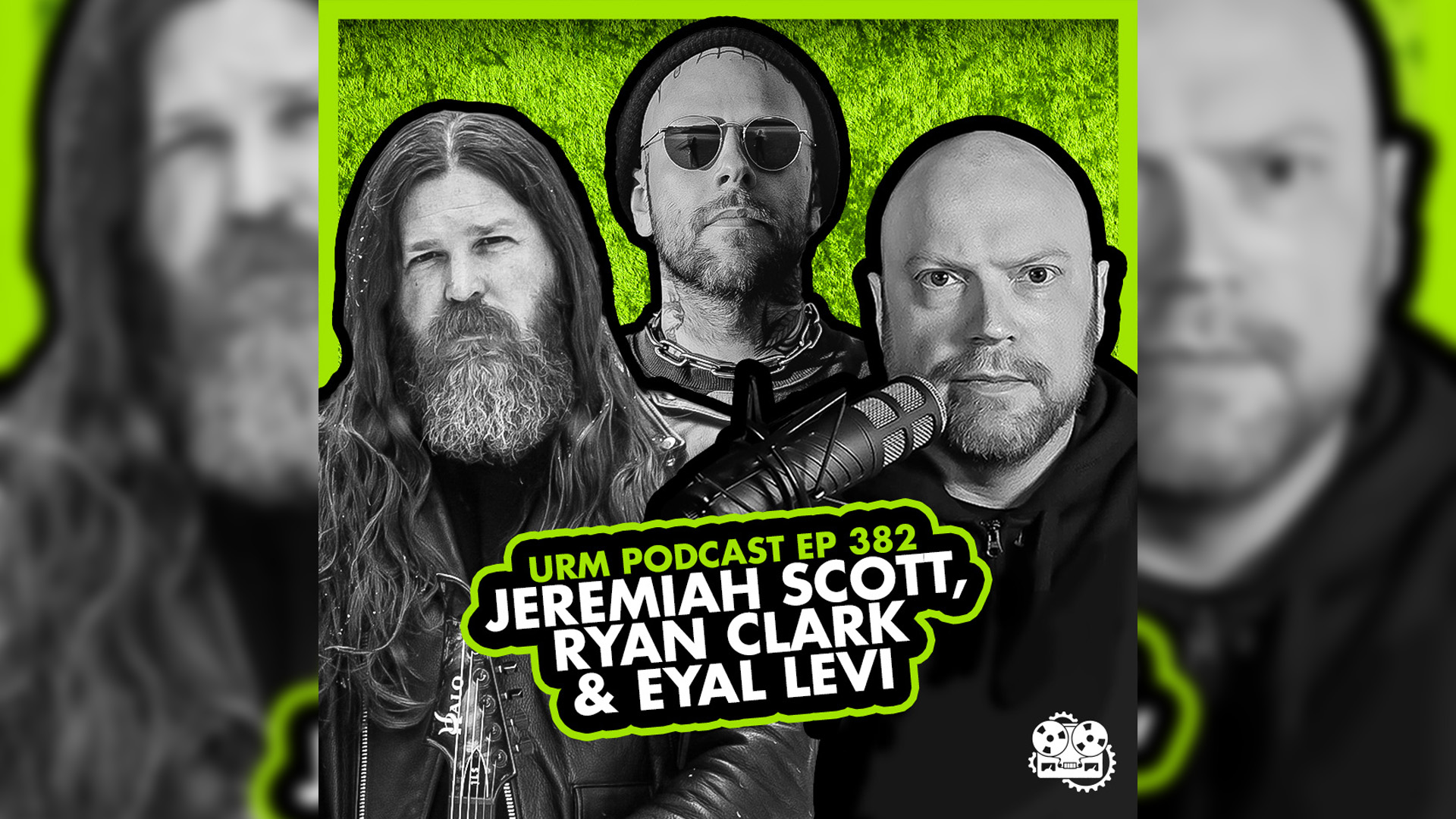

DEMON HUNTER: Going Independent, Mixing *Exile*, and Recording Horror Stories

Finn McKenty

Jeremiah Scott is a guitarist, songwriter, and producer for the metal band Demon Hunter, and Ryan Clark is the band’s vocalist and co-founder. While Ryan handles the band’s distinctive art and visual identity, Jeremiah Scott is the in-house production guru, having produced and engineered their records for the last decade. On their 11th album, Exile, the band’s first independent release, Jeremiah took on mixing duties for the first time, giving them complete creative control from start to finish.

In This Episode

Demon Hunter’s Ryan Clark and Jeremiah Scott drop by to discuss the process behind their first fully independent album, Exile. They get into the weeds on why extreme preparedness in the pre-production phase is the key to unlocking creativity—not stifling it—and how their DIY ethos extends beyond the music into every aspect of the band. Jeremiah breaks down the crucial decision to mix the new album himself, explaining how the record’s experimental nature and defined vision would’ve been a nightmare to hand off to an outside engineer, even one as trusted as their usual mixer, Zeus. They also share some hilarious and relatable horror stories about permanent recording mistakes, dealing with condescending live engineers, and the fine line between respecting your band’s brand and keeping things artistically fresh. It’s a super practical look at how a veteran band takes total control to get the exact record they want.

Timestamps

- [5:29] Demon Hunter’s philosophy on being hyper-prepared for the studio

- [6:30] “Twinkle sessions”: adding creative details after the main tracking is done

- [9:04] The bureaucracy of record labels and why they pay collaborators immediately now that they’re independent

- [16:13] Why being prepared allows for *more* creativity, not less

- [19:24] The realities of being in a successful band that isn’t your full-time job

- [22:11] Ryan’s take on why touring 300 days a year is a “stupid way of life” for people with families

- [24:07] The reason Jeremiah decided to mix Exile himself instead of using their regular mixer, Zeus

- [25:56] Breaking self-imposed audio engineering “rules” like using three drum kits at once

- [30:12] The DIY punk ethos behind making the new record entirely on their own terms

- [32:59] Getting to the point where you listen back to your own record and wouldn’t change a thing

- [36:28] The story of a permanent mistake on the song “Fading Away”

- [37:22] A guest vocal spot that ended up a half-measure off on the final recording

- [42:52] The anxiety of giving mix notes to a top-tier mixer you respect

- [48:00] How Ryan’s trust in Jeremiah as a producer evolved over multiple albums

- [53:45] The “tambourine in the chorus” trick they learned from producer Aaron Sprinkle

- [1:06:19] How Demon Hunter balances evolving their sound with giving fans what they expect

- [1:10:15] Discussing the band’s “brand” without it feeling corporate or contrived

- [1:12:16] Jeremiah’s origin story: a bad experience at a local studio

- [1:16:04] Dealing with condescending in-house live sound engineers

Transcript

Speaker 1 (00:00:00):

Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast. And now your host, Eyal Levi. Welcome to the URM podcast. Thank you so much for being here. It's crazy to think that we are now on our seventh year. Don't ask me how that all just flew by, but it did. Man, time moves fast and it's only because of you, the listeners, if you'd like us to stick around another seven years and there's a few simple things you can do that would really, really help us out, I would endlessly appreciate if you would, number one, share our episodes with your friends. Number two, post our episodes on your Facebook and Instagram, and tag me at al Levi URM audio and at URM Academy, and of course our guest. And number three, leave us reviews and five star reviews wherever you can. We especially love iTunes reviews. Once again, thank you for all the years and years of loyalty.

(00:01:01):

I just want you to know that we will never charge you for this podcast, and I will always work as hard as possible to improve the episodes in every single way. All we ask in return is a share a post and tag us. Oh, and one last thing. Do you have a question you would like me to answer on an episode? I don't mean for a guest. I mean for me, it can be about anything. Email it to [email protected]. That's EYAL at M dot A-C-D-E-M-Y. There's no.com on that. It's exactly the way I spelled it. And use the subject line. Answer me Eyal. Alright, let's get on with it. Hello everybody. Welcome to the URM Podcast. My guests today are Jeremiah Scott and Ryan Clark from the legendary Metal Band Demon Hunter. They just released their 11th album exile, and it's actually their first completely independent release.

(00:01:56):

I thought this would be a really cool episode because I actually have known Ryan for a while. I had him on Creative Live in my songwriting class, and he's a very, very interesting person with some great musical insight. And Jeremiah guitarist and songwriter in the band also produced and engineered the new album. So that would be cool to get the perspective of a self-produced artist that's doing great. I know that many of you listening to the podcast are self-producing artists, so it's relatable. Let's get this going. So Ryan Clark and Jeremiah Scott, welcome to the URM Podcast.

Speaker 2 (00:02:36):

Thanks, man.

Speaker 1 (00:02:37):

What's up? Glad to talk to you guys and glad to be catching up with you again, Ryan, because crazy. But it's been almost 10 years since that creative life we did.

Speaker 2 (00:02:47):

It's been 10 years since everything. Right?

Speaker 1 (00:02:49):

I know it does kind of feel that way, but man, that went by fast.

Speaker 2 (00:02:55):

Yeah, it did.

Speaker 1 (00:02:56):

Yeah, it's kind of nuts. So I checked out the new album. I love the way it sounds. Did you guys mix that or did Zeus mix it?

Speaker 3 (00:03:03):

I did actually.

Speaker 1 (00:03:04):

Okay, that's what I thought. I just wanted to clarify. I love how nasty it sounds.

Speaker 3 (00:03:09):

Is that good?

Speaker 1 (00:03:09):

Yeah, that's really very good.

Speaker 3 (00:03:11):

Nah, since I started producing for the band 10 years ago, Zeus was always the mix engineer, and this time around, I mean every record up until this one, I would record everything and produce everything knowing I'm going to hand it off to a mix guy. I'm talking, the sessions were clean, the wave files were perfect, all the edits were made. The naming, the first time I ever sent him anything, he responded back with immediately like, man, this is probably the cleanest session I've ever seen. Because I mean, I kind of work in the industry, so I know how I would want to receive the files, but there's also very minimal processing. No anything.

Speaker 1 (00:03:52):

Did you work on True Defiance? Were you in the band then?

Speaker 3 (00:03:55):

True Defiance? I joined in the middle of that being recorded.

Speaker 1 (00:04:00):

Did you do any of the engineering on that?

Speaker 3 (00:04:02):

Nope. That was all Aaron Spring. Yeah,

Speaker 1 (00:04:04):

The reason I'm asking is because I was mix engineering for SKO back then. True Defiance was one of the first records that came in when I was working for him, and I remember how well prepped everything was. It was maybe the best prepped project that I ever worked on in my time there.

Speaker 2 (00:04:23):

Well, it was Aaron did the record, but who was his assistant at the time? It might've been Matt. It was Matt from Emory. Yep. I don't know for sure. I don't want to take it away from Aaron, but it could have been Matt that actually cleaned everything up and sent it over.

Speaker 1 (00:04:36):

Well, it's everything that Jeremiah was just saying, the standard equality of everything in that session, the way it arrived was just the way you wish. Everything was always delivered, and so that's when you started talking about how you would hand stuff off. That's what that made me think of. That kind of seems like how demon Hunter rolls basically.

Speaker 3 (00:04:58):

I mean, Aaron, I've worked with him a bunch since then, and I will say that still to this day, whenever I do get something from him, it's pristine. So if it was Matt doing all that file prep for mix before doesn't mean Aaron doesn't also do that, and I still appreciate that. And then I send to him the same kind of stuff, and then we're never complaining about the files. You know what I mean? Because we're pros and we're going to treat this the way it is so he could just jump right into working on it and so could I.

Speaker 2 (00:05:29):

Yeah, I think that is kind of like a calling card of ours, at least a little bit. Preparedness and professionalism are things that we really want to lean into and want to be known for. I think a lot of bands seemingly at least, they sort of wing a lot of aspects, whether it's in the artwork or it's the photo shoots or it's the videos or it's the showing up into the studio with half the songs written or half the lyrics written or just things like that. I hear about that kind of stuff all the time. Oh, it's real. It couldn't be further than the way that we operate as a band because every little tiny aspect is thought about, done, prepared. We leave a little bit of room in the final stages to be creative. We call it a twinkle session when the record is basically recorded the way it was on the demos, and we basically reapproach everything and we go, okay, what could be added?

(00:06:30):

What could be taken out? What could be simplified? What should be? Could we tweak the structures first of all? And then beyond the structures, can we start adding little details and elements and things like that. So there is a little bit of that towards the end just to keep it fun and get the most out of the songs. But when we show up to record a record, it's so thoroughly fleshed out. And by that time, I mean honestly, all the song titles, the album title, the artwork's already underway, probably the title for the next album is already decided. We're just so intent on being really, really prepared and really professional, and I think it just bleeds out into every single thing that we do. And there's enough of us in the band that are really proactive and really care about that kind of stuff that I think it's a real driving force for what we do.

Speaker 1 (00:07:25):

Do you think that because you guys are in the industry and our pros, that you're aware of what happens when you don't come prepared and all the BS that goes with that? So do you think that just having that kind of understanding of how most things operate in music, it pushes you to do it the way you would want to receive things?

Speaker 2 (00:07:49):

A hundred percent.

Speaker 3 (00:07:50):

Ryan and I are both very discerning and very critical, and if somebody is not operating a hundred percent, we might nudge 'em to operate at a hundred percent, or I'll push 'em aside and say, well, I'll just do it. That goes like he's talking about all the aspects of the band, even our live production. I handle all that, and then I could divvy it out to one of our techs or our front of house engineer. But if they're not really, this isn't their baby, but this is my baby, so I'm going to design the production. And even Ryan, I would say just, he can say more about this, but our deluxe editions for our records, if the label's kind of like, we don't know, they don't seem like their heart's into it, then he's like, well, my heart's into it. So he just makes it from top to bottom and creates everything about it. So a lot of pieces of this band from the record, from the songwriting to the merchandise to the live shows and all that has our thumbprint on it more than I think most bands.

Speaker 2 (00:09:04):

Yeah, just the normal operating procedure of entities like business entities, bands, record labels is sort of wrought with a ton of red tape and a ton of bureaucracy and way too many decisions, way too many people making decisions. We try just because of having the sheer experience that we have and collective experience that we have. For me, I've been in signed band since 1996, so 26, 27 years. So with that said, it's like I've taken everything that I've seen in the industry and everything that's sort of annoying and doesn't really make sense to me. And yeah, like you said, I'm basically trying to, now that we're fully independent and we're not beholden to anyone, how would we do things? For instance, Jeremiah was talking about the deluxe edition. If we're going to do this comic for this deluxe edition, when I hire these guys to illustrate or to letter or to color, we're not going to function like a normal record label and pay them at net 60 because that's stupid. And everyone knows it's stupid and it's just bureaucratic nonsense. So instead, I'm going to pay them the second that they ask for it. When they invoice us, we will pay them or whatever that day right then and there, isn't that nice? Isn't that how everyone would like to be paid for the work that they do? It just makes sense.

Speaker 1 (00:10:34):

Dude, it's funny you say that because at URM, that's how we handle it too. People always get paid fast, and it's always been that way because of my experiences as a producer waiting six months to get paid in some cases by a label, a record comes out and I'm still waiting on the down payment, stuff like that. Enough of that happened to where when URM started working with outside producers, besides myself and the other founders, we've always pushed that we pay people immediately. And if there's a delay, that's the exception. In seven or eight years, maybe there's been three or four times that something's gone delayed, but it's totally the exception. It's because it just doesn't make sense to me to make people wait that long. It just why?

Speaker 2 (00:11:29):

Because it's just a game of moving money around and making sure there's a certain amount for this or that or taxes or investors and things like that. It's just become sort of a game, especially with these large companies. But if you can, the beauty of having your own thing and doing it your own way and keeping it small and being scrappy is that you can do things like that. And despite not having a dedicated person to pay bills, which all these record labels do, despite not having that, you can just jump right in there and just take care of it. And this is just sort of an analogy for how everything goes for us, it's showing up in the studio and being 100% prepared, having all the lyrics, all the melodies, even harmonies, just everything sort of sussed out that's being respectful to everyone else involved. That's being respectful to the producer, it's respecting the process, but it's also respecting everyone else involved. And that's like you can make those sorts of decisions, you can do that sort of thing if you're dedicated to the thing and the more passionate you are about the thing. I feel like these sorts of decisions are just going to come naturally. It's just respecting the process and respecting everyone.

Speaker 1 (00:12:44):

What's funny about respecting people and wanting

Speaker 2 (00:12:45):

The best thing when it comes, at the end of the day

Speaker 1 (00:12:47):

Preparation, I've thought about

Speaker 2 (00:12:48):

This,

Speaker 1 (00:12:49):

Is I think a lot of people have the attitude that, well, if you're paying them, then they shouldn't get mad about you needing more time or being unprepared or stuff like that. But it's like, dude, money is one thing, but the human side of this matters just as much if not more. And no amount of money makes up for the interpersonal side of it and

Speaker 2 (00:13:18):

A hundred

Speaker 1 (00:13:18):

Percent the basic human respect. And when you treat people like that and take into consideration their time, and also if you're thinking purely selfishly, if you want to get the best out of people on your project, the less bs that you consume them with, and the more that you just allow them to get to work, the better the outcome's going to be.

Speaker 2 (00:13:43):

Right? And I mean, if you think about the way that other businesses operate, let's say you have a plumber come over and it's just a good experience, which is probably kind of rare if it's just like they stay out of your hair when they should, they don't talk you to death, they don't keep you too long. All those sorts of things where it's just sort of respecting your time, it's taking those sorts of aspects of just regular business interaction and integrating them into something like this. Being in a band and sort of all the different moving parts, it just, not only is it a nice human thing to do, but for me, this is also a business for me and Jeremiah, and we're not so swimming in money that we can just balk at the idea of return clientele. So if I treat people with respect and I'm professional about the way that I interact with people and I'm really good at what I do, I can sort of assume that that's going to be a return client for people that I guess don't need to worry about return clients or spreading a good name about your work and how good you are and maybe how fast you are at being good and all those sorts of little aspects.

(00:15:11):

I guess some people can sort of skirt those things financially stable, but for those of us who work for a living, it's not possible to have a business model where you, you're thinking selfishly and you're not thinking professionally. And for me, it's absolutely important.

Speaker 1 (00:15:32):

Man, I worked with somebody, I'm not going to say who, but I worked with somebody very closely who was, I would say, at the top of the game at one point in time, production wise, definitely not saying who. And dude got kind of lazy and just started kind of messing around with a client's time. And I remember I asked him, don't people, doesn't this piss people off? Doesn't it cause problems? He said, I made it. I don't need to work that hard anymore. And wow, I can't believe you just said that. And many years later, he doesn't have even 10% of the amount of business.

Speaker 3 (00:16:13):

Of course. I want to expand on what Ryan was saying about being prepared in the studio. I think everybody needs to hear this. It's one of those questions that people ask us. It's like, oh, well, how do I break into this and how do I do that? And I'll give a little short list of some advice, and this is one of 'em, but when Ryan says, we come into the studio prepared fully, he's got all the lyrics and everything. It's not like it's all fleshed out and we're just going to do the work and then call it a day. I mean, we're that prepared so we can get to work immediately. Yes, but we're not clocking time. Well, let's be creative and write a verse in the studio, but because we're so dialed in and ready, we can be creative when it falls in your lap, sometimes it doesn't.

(00:17:04):

A lot of this record is very different from the demo, even though the demos were majorly prepared. But I mean, Patrick does it too. And he comes in, that dude sits down, puts his guitar in his lap and is just like, let's go hit record. And he will nail these parts. He's been playing 'em for months because he has, and he's prepared like Ryan is. And Ryan goes in and he's not second guessing his lyrics or even the harmonies, he's got it down, but we're knocking out songs like three songs before noon, and then we're like, Hey, what if we played with this guitar? Or what if we tried this riff a little bit differently now because we were so cowboy with how we're going to approach this thing and we're ready to go now we can let those creative juices hit us and not feel guilty like we are wasting somebody's time in the studio because man, I produced however many bands and one of my least favorite things is to see the singer sitting on the couch behind me trying to write lyrics and go play that again.

(00:18:09):

Play that section again. Play it. I'm like, dude, go home and you play it. I'm like, go sit with your guitar player and play it. You should have done that months ago or weeks ago, or the guitar player trying to come up with solos. Even now, Patrick's my boy, and if Patrick's like doesn't have something nailed for a solo right away, we just, let's write a solo section right now on the spot. He's like, okay, he'll play with it for five minutes. And he goes, let's move on. And then that dude that night goes home on his own time and then shows back up the next day and nails it note for note. So

Speaker 1 (00:18:42):

That's

Speaker 3 (00:18:43):

That level of preparedness. It allows us to also do that, not just be respectful of everybody's time. That is very important. But if you're also trying to want to tap into more of the creative process and make the most use of it, and again, like he said, we don't have all this money and to just do whatever, so we can't just rent out. I mean, I wish I was Metallica and I can just rent out a studio for a year and do a record, but we can't, who does anymore? You know what I'm saying? Who has that anymore these days to just go into a major studio and just rent block the whole thing out for a year? You know what I mean?

Speaker 2 (00:19:24):

It would be amazing. Yeah, everyone's dream to like, yeah, let's go away for three months and write a record. That's a fantastic thought on paper. But on top of not having the money to do it, having the time just as either people that are, again, working for a living demon. Hunters had a nice amount of success, and in the industry we're very lucky, but that's not my full-time job. It hasn't been the whole 20 years When I'm working on demon hunter, I need for it to work smoothly and quickly. To some degree. I can't jeopardize the time that I have allotted for Demon Hunter because on top of work, it's like we all have families, we all have kids. We have so many irons in the fire when we are going to sit down to do demon hunter, when I fly out to Nashville to track vocals or be there for drums or whatever, I can't squander that. I can't squander that time at all. And in order to not squander it, there's a certain amount of preparation, professionalism and sort of being in the moment and being ready for it. That is absolutely necessary, especially for a band like us who, it's not any of our full-time things yet. We release albums probably more frequently than the average band.

Speaker 1 (00:20:32):

I mean, 11 has nuts. One thing I've always respected about you guys is that it's not your full-time thing. And I've always thought that it's really inspiring and that people should pay close attention to that because the idea of a band being your only income stream in the modern age, that's also a fantastical thought. I mean, it's doable, but it's super, super rare. And so to be a professional music person, and I say music person, because there's so many different things you can do in music that go beyond just making music. In order to be a professional music person in the modern age, you're probably going to have to do a few different things. And if a band is one of 'em, you're probably going to have to work with limitations. Limitations of time, limitations of budget. But I think that there's this myth out there that you have to only do your band and you can't have real success out there, real success in the industry beyond a local level without doing it full time. And you guys are proof that you can do it and also do awesome things with it

Speaker 2 (00:21:46):

If you want to be on the road pretty much all year. If we wanted to do that for instance, we could probably make a pretty good living doing it, because when we do tour, it's a nice little bump for all of us, or at least in recent years it has been. It's not always been the case. But we don't want a tour, honestly, if I'm being totally honest, people with families, I think it's actually a really stupid way of life.

Speaker 1 (00:22:11):

I mean, I think people above a certain age,

Speaker 2 (00:22:13):

Yeah, that's for sure. And people that have a certain amount of responsibilities, those a combination of those two things, it's a lot of fun. And it can be. There's a certain level of it where I feel like it begins to get really selfish at a certain point, and I think it's a lifestyle that people have just sort of become accustomed to and gotten used to. It's almost like having a spouse in the military or something like that. But at the end of the day, I can't help but think, do they have to do that to the detriment of their kids growing up without 'em and all that sort of stuff that happens. You see things fall apart very clockwork. When a band is on the road 300 days a year or whatever, it's never a good outcome with regards to what's happening back at home.

(00:23:05):

So for us, that's something that we just don't really want to do. We still love touring, and I think we love it and we enjoy it, and we have a good time with each other because we don't do it so frequently. It's like you also hear about band members who just kind of don't like each other and just don't really have a good time touring anymore, and it's just become a job. And dude, for us, when we get up and play every night that we're on tour, it's like the best thing ever for all of us. We're having the best time. And I know it's not like that for bands that tour a ton.

Speaker 3 (00:23:38):

No, definitely not. We're rare in that sense. Worked with a bunch of bands and toured with other bands, and you see, oh, those two guys don't like those two guys in that band, or that's the heel in that band. But yeah, we genuinely enjoy each other, love each other, do stuff outside of the band with each other just for fun. That's rare too, man. And that helps out a lot. You guys don't mind? I wanted to, I never did finish my thought about when you asked about exile sounding.

Speaker 1 (00:24:05):

Oh, yeah, yeah, sorry. Yeah, go for it.

Speaker 3 (00:24:07):

I think it's important to mention what happened there is we had Zeus mixing everything really. I don't want to throw Zeus under the bus at all. It would make it sound like I was because, and why we decided for me to mix this. We still love Zeus, still work with him. He mastered it. And dude, he's the, but like I said, I had all the sessions for all the previous records, so tidy, and it was like a metal record. This is a metal record guitars, some synth vocals doing this, drums doing this. You get it, mix a metal record. But when we did exile, things started getting hairy and I would say experimental. And that was an intentional thing for me and Ryan and Patrick when we were coming up with the new sound or should we make a new sound? What should it be?

(00:24:52):

And then we can get into that if you want, but it was something that was in our heads that we had many, many hours of discussion about that in order to see it come to full fruition with the mixed guy, Zeus, let's say, it would have to be hours of convincing him or explaining to him what we're going for. And I didn't want to miss it. And so for the first time ever, I had a session with piles and piles of plugins doing this and processing here and there where I've usually had it all stripped down. Now, that might've also been because I just finished building my own studio and I had a new computer that can handle a heavier load finally, and I've also started embracing more modern. I was always kind of like a, no, it's got to be this old school reverb and this compressor. And I went and looked to new stuff. I was kind of an old curmudgeon. You know what I'm saying? It's got to be done this way. Then I started going, no, it doesn't have to be.

Speaker 1 (00:25:54):

It can be done however you want it to be done.

Speaker 3 (00:25:56):

I started breaking rules that I put on myself, I guess us as audio engineers put on each other. I started breaking those rules a little bit and then started seeing that the sound could be changed. Who says there can't be three drum kits going at the exact same time? I've never, well, that's just dumb. Maybe, but why not? And then, so this is just a culmination of all these conversations, especially with Ryan and I have had about what makes this record crazy or what makes this one sound different? And then, oh, they broke the rule there. They broke the rules there. So anyway, I had a whole session, a whole record, and by the way, it's almost 80 minutes long. That's two records. So I didn't want to be like, Hey, Zeus, you want to mix a record? And he's like, sure. I go, by the way, it's two and it's not 12 metal songs. It's stuff all over the place. The kick drum and the snare is not at all the same on any of the songs, and the guitar tones are different from each song to song. It's like whenever a mix engineer, whenever you get a record and then, okay, here's 12 songs of this band, and then you mix the first one, the middle of the road song, and that becomes your starting point.

(00:27:08):

Well, every song's going to have to be started over from scratch every single time. I was like, dude, the workload that Zeus is going to have is four to five times a normal record, a B. Will he even understand what we're trying to do? And that's if he doesn't, it's not his fault just,

Speaker 2 (00:27:28):

Well, it's stuff we'd been talking about for months. It would be downloading him.

Speaker 1 (00:27:32):

How would you just drop somebody into that dude? So what you're saying right here, I think is a super common thing among bands that have very defined vision, and especially when you have people in the band who are capable engineers, producers, mixers, and have that passion for the band itself that Ryan was talking about earlier. I feel like this is a natural thing that happens. Bringing in an outside mixer I think is a very important thing to do. First of all, if no one in the band is capable, obviously it's super important, but also earlier in a band's career, it's really, really important I think, to bring in somebody that can level the sound up. But I mean, the more off the beaten path or the more defined a vision is, the harder it becomes to just drop someone into it, I guess, after 80% of the work's done, and expect them to just understand where it's supposed to go.

(00:28:34):

Now, I feel like sometimes that is what you want. You do want someone who's going to have a totally impartial take on it and is going to take it their way. But if that's not what you want, you have a vision, you've been working on this forever, you know exactly what it's supposed to be. It can be a very frustrating situation to bring in a mixer, and it's not a knock on the mixer. This happens with some of the best mixers in the world where it's just the reality of coming into a project that is already so I guess defined that would be the word.

Speaker 3 (00:29:10):

And this goes against what we're always saying, which is like, man, record your stuff, but

Speaker 1 (00:29:16):

Bring a mixer

Speaker 3 (00:29:17):

And mastering this is saying something different though. So I do want to point out that I do realize the value of that. Hence, we've had Zeus mix everything, and then as soon as we send it to him, first rounds were amazing. Maybe bumped this one thing, but he was killing it. So do I think he wasn't going to kill this one? No, he was a different thing. And I wasn't burnt out on the record because we spread it out over time. I would put it down for three or four weeks and then pick it back up. And then I was so in love with it and so involved that I wasn't burnt out. That's what everyone's saying. You don't want to get burnt out, so send it to somebody else. Fresh ears. Well, I kind of kept coming at it with fresh ears all the time. So there's value on both. But for this instance, it was probably going to be a little harder. And then, dude, seriously, the workload is going to be five times easily.

Speaker 2 (00:30:12):

I think there's two sort of separate but equal aspects to this. It's what you're saying, Jeremiah is its own thing. Having to download all of this information to someone about conversations that we've had for months and hour, long hours and hours of conversation, ideas and nuance and all that kind of stuff, and trying to get someone ingrained and on the same page, that's sort of like a what you don't want to have to do side, which is important, is like, we don't want have to do this because again, we're trying to be as productive as possible. We're trying to use our time really well. But then there's the other side of that coin, which is what we do want to do. And for this record specifically, especially what we did want to do is as much of it as possible by ourselves with no outside help.

(00:31:01):

So that's another massive aspect of a point of pride and a feather in our cap for this record specifically, which was can we release this on our own? Can we essentially start our own little record label? Can I source all of the product myself, between me and our manager? Can I do all the art myself? Can I write the comic book myself? Which is something I didn't plan on doing at first. Can we record it all ourselves? Can we do it in our own studios? Can we mix it ourselves? What part of this can we not do and the things that we can't do or the things that we want done to a better degree than we could do? IE the guy who illustrated the comic book, I know where my limitations are, I know my wheelhouse, I can illustrate, but not like this dude.

(00:31:52):

So at a certain point, you have to do what's right and best for the project. But coming from that nineties hardcore ethos or punk ethos, which we are all coming from the pride that comes with doing as much of the thing as possible by yourself doing it, DIY, figuring things out, being scrappy, saving money, cutting corners that are good corners to cut, but not cutting corners that are necessary to keep all that sort of stuff. And being thinking on your toes and just being your own manager and your own, dictating your own time and the people you want to work with and the people you don't want to work with, and when you want to schedule the music video and who you, all that sort of stuff that, again, these entities sort of get in the way of just being effective and scrappy. How much of this can we do on our own? And I think mixing it ourselves was also just another aspect of like, can we do it? Can we do it well, would it be cool to do? Would it be fun? Would it be an extra feather in our cap? Then let's do it. And so everything was that way.

Speaker 3 (00:32:59):

I mean, every project you work on, record, record you write, there's always that little list at the end where you're like, ah, I would've done that differently. When you're listening back to it a year later, two months later, five years later, this record might be because we kept it all, did it all ourselves, and we nitpicked so much that, I mean, there might be two of the smallest, stupidest little things that I would change. But other than that, man, I mean, how often do you get to say that? You know what I'm saying? You work on a record and then you're like, wouldn't change anything about it. That's exactly how it's supposed to be. That's how it was in our heads. That's it. I mean, that never happens, but so that was one of the benefits of this is Ryan would even call me up if one little thing was bothering him. He had the freedom to tell me, and then I'd be like, absolutely, sure. And then we just kept doing that. I mean, our little list of things to fix or change was massive, and it just kept growing and growing and then shrinking and then shrinking, and then we whittled it all the way down to nothing. And I think that attention to detail comes out in this record

Speaker 2 (00:34:08):

So that, again, you can throw all of this stuff on either one side of that coin or the other side of the coin, which is that huge list that you're talking about,

Speaker 1 (00:34:17):

What you do want and what you don't want.

Speaker 2 (00:34:19):

Again, when you hand something over to a mixer, even if it's someone that's really going to kill it, there's always a handful of things that you want to change along the way. And at a certain point, if you're not exactly hearing it the way that you want to sort of go, okay, I guess it's fine. And that happens every single record, no matter what, that'll happen a couple times unless you're a total, we don't want to operate that way. I know that people do.

Speaker 1 (00:34:44):

It sucks. It sucks.

Speaker 2 (00:34:46):

Yeah. I know that there are guys in bands that'll just punish mastering engineers or mixers or whatever, and they'll just keep them on call for weeks and months about the tiniest little nuances of songs. But I don't and can't operate that way. So at a certain point I'll be like, that's fine. And this allowed us to not ever have to be like, ah, it's fine. It was every tiny little thing. I was like, can you bump that up? Just the tiniest?

Speaker 3 (00:35:11):

Can we tell them about the second or third record? Can you tell this story? This is one of those, I mean, I know production guys and bands to hear this kind of stuff. This is how Ryan will just roll over for some things. There's

Speaker 2 (00:35:22):

Several stories like that, dude.

Speaker 3 (00:35:24):

But tell the one about the lyrics ending. I think you think Sprinkle accidentally flew a section over. Just explain that. Do you know what I'm talking about?

Speaker 2 (00:35:34):

Okay, so there's several of these, trying to remember what song it is. It's on Summer of Darkness, I think it's called

Speaker 3 (00:35:40):

That. Well, the way I remember it is if you read the lyrics, there's a phrase,

Speaker 2 (00:35:45):

There's sort of a call and response thing. It's like a scream and then a sing, and then a scream, and then a sing.

Speaker 3 (00:35:50):

But the song ends in the middle of it or something.

Speaker 2 (00:35:52):

No, no, no. What happens is the scream and then sing and then scream, and then sing is a complete thought. And then somehow the screaming sections got paired together, and then the singing sections got paired together and sort of separated, and those phrases now don't really make sense. And it was just sort of flowing into place and I was like, ah, that sounds all right, but now the lyrics don't make sense. And I was just like, it's worth, it's not worth.

Speaker 3 (00:36:18):

Yeah, you didn't want to bother the engineer to the extra

Speaker 2 (00:36:21):

Day. You don't want to be that guy. Yeah. I mean, another one is Fading Away has that stupid

Speaker 3 (00:36:27):

Yep.

Speaker 2 (00:36:28):

Five measure, three measure thing in the bridge, and it's a legitimate mistake. It's on record forever as a legitimate mistake. If you listen to the bridge of that, it's got this breakdown thing, and at the end of that breakdown it does five measures and then three measures instead of four and four kill me. And it makes it really complicated for a band like us who doesn't work with off time signatures or weird parts like that. It's just not in everyone's bones. So when we go to rehearse that if anyone's rehearsing to the record, it's like, oh man, it's really annoying. You have to ignore it or try and work your way through it. Yeah, there's another one that I don't think I've ever actually told anyone. I did guest vocals on a song for Impending Doom. It's the only one I've done, so you could find it pretty easily.

(00:37:22):

It's one of those songs where they just, every once in a while band will do a song and they'll just sort of send me the instrumental and they'll be like, can you write something to it? I recently did that also with Holy Name on a new song that they're releasing soon. But usually it's like, here's the part. Can you either sort of adapt it and do your own thing or whatever? There's a couple of instances where it's been like totally blank canvas, so write the lyrics, write the melodies, whatever this impending doom song was that It was, I think entirely instrumental. And so I wrote the vocals to the song just like you would normally just top line stuff. And I sent it back to whoever their engineer was at the time. I don't know where the disconnect was. It was probably my fault. I don't really know what I'm doing in terms of recording and engineering and stuff, but the song came out and the whole entire take, or the whole entire finished vocal is like a half a measure off, and it does line up and it sounds cool in its own way, but it is not how I recorded it, and it's the whole song.

(00:38:31):

So it'd be interesting for people to hear the way that I actually intended it.

Speaker 3 (00:38:35):

So that happened to me with Soul Embraced Rocky Gray from, he was a drummer for Evanescence, and he's the guitar player for Living Sacrifice. And Rocky does, he's an amazing musician. He does a bunch of percussion for us on our records, and we love that guy. And he's sick, very talented, but I wouldn't say he's an engineer first. Okay. Mean you know what I'm talking about when I say that. But he can engineer, but he's not an engineer first. So he had Soul Embrace and he sent me over a section to do a guitar solo on, and I listened to it, and I did the solo, but I kept trying to ask, are you sure? What's the beat marker where? And then it was just the session wasn't clean and labeled properly, and I did a solo, I wrote it over this really weird dissonant part. Oh man. And he flew it to a very melodic part that I would've loved to write a solo over. And then I didn't even hear it until the record came out, and I was so bummed, and he goes, this sounds cool. I'm like, no, it doesn't. That's not what I was trying to do, man. I feel like Samuel Jackson trying to act on a Star Wars movie, but just staring at a green screen and you tell me that there's a lake there, but instead it's a mountain. I don't know.

Speaker 1 (00:39:59):

I just had an experience with that. I know what you're talking about too with that stuff is there's at some point where you don't want to be an asshole and it doesn't feel worth it to just keep bringing it up. So my band just got our new stuff mixed by Jens Boren, who is great, amazing, love him. And the way that I structure guitar parts is that lots of times I quad everything or do eight rhythms, and often the quads will not be playing the same thing. It's not four independent guitar parts, but

Speaker 2 (00:40:40):

An octave of it or whatever.

Speaker 1 (00:40:42):

Yeah, yeah, exactly. It'll make a bigger chord,

Speaker 3 (00:40:45):

For

Speaker 1 (00:40:45):

Instance, like a four part cord, and it's

Speaker 3 (00:40:49):

Wait to be clear, you're not doing the same exact thing four times per side. You're slightly

Speaker 1 (00:40:56):

The same rhythmic pattern, but yeah, but it'll be like four independent, four different inversions of the same cord or something. There's only one way it can go, because if you start panning things the wrong way, it's going to start to sound like garbage. It's designed to be panned exactly the way it's designed to be panned. And something happened with this one of the songs where Yenz, I don't know if we sent it to him wrong or he made a mistake, it doesn't really matter, but point is I was sitting in the control room and something sounded mono in the song. It's just like the guitar sounded mono, but I knew they weren't mono. I couldn't tell what was going on. I couldn't hear the spread, and I just said, man, something's weird. Are the guitars maned or what's going on? But he's such a great mixer and I have so much respect for him that I didn't want to say it.

(00:41:56):

I felt really bad saying it, and I didn't want to rock the boat. It still sounded kind of cool, but it was just wrong. The thing is, his guitar tone was not just four parts. It's like every part was a blend of three amps. So not only was it very specifically constructed on my end, the mix itself, the guitar tone in the mix is very specifically constructed on his end too, and it's not the same thing on both sides. So just redoing it is, it's not that simple. You can't just flip the pan and then it's fixed. It required him to basically go from scratch. And so once we realized what was going on was just, he had two of the guitars flipped, panning wise, that's all it was. And he offered, he was like, you know what? Give me 30 minutes. I'm going to reamp from scratch. Don't worry about it. And I was like, thank God he said that,

Speaker 3 (00:42:50):

But it killed you a little bit to have to bring it up to him, right?

Speaker 1 (00:42:52):

Yeah, man, I felt so bad having to say it. And the thing is, he's a total perfectionist.

Speaker 3 (00:43:00):

Of course,

Speaker 1 (00:43:01):

He's the one that was cool to just go fix it. But yeah, a little piece of my soul died having to say something was wrong.

Speaker 3 (00:43:10):

Imagine having a record where there's 20 weird little things that need to be just like this per song. That was the exile. That's why I was like, dude, I'm going to have to try to mix this, and even if it takes me months to get where we want it to be, it's still probably going to be way easier. And then Zeus is not going to hate us because it was going to be me messaging Zeus over and over again, and eventually we're just going to get worn out and we're just going to roll over on the fact that this isn't panned right, or the effect isn't correct on that vocal. That just goes back to again, why I was like, I'm going to mix it. And then we mixed one in the middle of the road, a song called Chemicals. I think it was Ryan. Was that the first one? I did,

Speaker 2 (00:43:56):

Yeah. Yeah. I mean, in earnest it was.

Speaker 3 (00:43:59):

I did it, and Ryan knows he could be honest with me. He's not brutally honest. You won't be brutal won't be mean. No, no, he's never mean either. But his criticism is great, and I appreciate it.

Speaker 2 (00:44:10):

I'll say everything that I want to say. I just might say it a little bit nicer than I should,

Speaker 3 (00:44:15):

And he doesn't have to me, he can get

Speaker 2 (00:44:18):

Meaner,

Speaker 3 (00:44:18):

But

Speaker 2 (00:44:19):

I feel like there's just something.

Speaker 3 (00:44:23):

So we did chemicals, but probably because I had done all this work in the tracking session and editing phase, I think I mixed it in an hour and a half, two hours.

Speaker 2 (00:44:35):

Well, also we were pseudo mixing along the way.

Speaker 3 (00:44:37):

That's what I mean, and that's the first time I've ever really done that, because I don't do that usually for a record because I want to send it to Zeus and be wowed at the end. But this time, because the way the mix was reliant for the song, so I would be mixing along the way, so when I got down to do it, I didn't just erase everything. I kind of went, okay, let's put things in their place and then sent over something like an hour and a half later, and then Ryan's response was like, man, if that's it, that's what's on the record. I'm happy. And then that was very a big relief for me. And then not every song went that way. I was like, what's wrong with this one

Speaker 1 (00:45:17):

Still? That's super validating though.

Speaker 3 (00:45:19):

And then I was like, okay, great. I got the confidence to do it and then let's, let's just go for it. And then started knocking 'em out, and then, yeah, can I think I have six or seven revisions on a few of the songs, and some of those are mostly mine, because going up and down with that high hat, you know what I'm saying, or overhead, it's always something stupid like that where it's like half a db. But other than that, we did a lot of revisions because we can, because we're not bothering Zeus or bothering Jens, you know what I'm saying?

Speaker 1 (00:45:49):

Hey, everybody, if you're enjoying this podcast, then you should know that it's brought to you by URM Academy, URM Academy's mission is to create the next generation of audio professionals by giving them the inspiration and information to hone their craft and build a career doing what they love. You've probably heard me talk about Nail the Mix before, and if you're a member, you already know how amazing it is. The beginning of the month, nail the mix members, get the raw multi-tracks to a new song by artists like Lama, God, angels and Airwaves. Knock Loose eth chuga, bring me the Horizon. Go Jira, asking Alexandria Machine Head and Papa Roach among many, many others over 60 at this point. Then at the end of the month, the producer who mixed it comes on and does a live streaming walkthrough of exactly how they mix the song on the album and takes your questions live on air.

(00:46:41):

And these are guys like TLA Will Putney, Jens Borin, Dan Lancaster to Matson, Andrew Wade, and many, many more. You'll also get access to Mix Lab, which is our collection of dozens of bite-sized mixing tutorials that cover all the basics as well as Portfolio Builder, which is a library of pro quality multi-tracks cleared for use in your portfolio. So your career will never again be held back by the quality of your source material. And for those of you who really want to step up their game, we have another membership tier called URM Enhance, which includes everything I already told you about, and access to our massive library of fast tracks, which are deep, super detailed courses on intermediate and advanced topics like gain, staging, mastering, low end and so forth. It's over 500 hours of content. And man, let me tell you, this stuff is just insanely detailed.

(00:47:35):

Enhanced members also get access to one-on-ones, which are basically office hour sessions with us and Mix Rescue, which is where we open up one of your mixes and fix it up and talk you through exactly what we're doing at every step. So if any of that sounds interesting to you, if you're ready to level up your mixing skills in your audio career, head over to URM Academy to find out more. Ryan, out of curiosity, you have worked with so many great mixers and producers at this point. How did it get to the point where you trusted Jeremiah to take that over? And the reason I'm wondering this is because oftentimes there is, in modern bands, there's always one person who's the engineer guy or two, it's a modern thing, but it's not that normal though for that person in the band to be an all out professional producer, engineer. They're usually just amateur. Sometimes bands will let that person do stuff just out of default, but they secretly don't want to. I know that that's not the case here. So what I'm wondering is how did it evolve to the point where you had the full trust in a band member to handle something as major as this? It

Speaker 2 (00:49:00):

Wasn't an overnight thing for sure. If you see sort of the trajectory of how things started shaping up, starting with Extremist, that was very much a blend of like, okay, Aaron Sprinkle is still a part of the equation. He had moved from Seattle, Aaron had moved from Seattle to the Nashville area. Jeremiah was at that point, a new-ish band member. At least that was his first going into an album. That was his first time with us. And it only made sense that, I mean, we've got, so we've got Jeremiah, he's got a home studio, he does record bands, he does a great job of engineering. That answers a ton of questions for us in terms of when can we record, where do we have to go to record, how much is it, all this kind of stuff. With him being sort of our in-house dude, it answered a ton of questions. And so with Extremists, it was like, okay, well let's do everything with Jeremiah in his studio. And then I still really want to work with Aaron because there's kind of like mathematical thing that I feel like, especially at that time, having done the four records prior to that, doing vocals with Aaron was sort of like, I could make sure that I was hitting things or finding things that weren't necessarily second nature to me.

Speaker 3 (00:50:30):

Yeah, clean vocals.

Speaker 2 (00:50:32):

Yeah, yeah, specifically singing vocals. So when I would go in with Aaron, I would be like, okay, here's the part. And then he would be like, sing, we're doing harmonies. Sing this thing here, or do this mono note harmony thing here. Interesting things that are not go-tos for me, Jeremiah will tell you I have sort of harmonies that are, I don't know what it is, maybe a fifth or whatever, but harmonies that are super go-to for me and I'll do it almost second nature. Aaron had this way of being, what about this? And it'd be some really interesting thing that really kind of broke me out of my shell. So I really enjoyed that aspect of working with Aaron. So extremist was like, alright, I'm going to go over to Aaron's studio when I'm in Nashville when we're doing extremists, I'm going to do singing vocals and then go back to Jeremiah's house and we'll continue doing drums, guitars, screaming vocals, all that stuff. So that was how that album was. And then with Outlive, it was similar, but now Jeremiah's recording all the singing vocals and we're just sending them to Aaron to sort of polish up a little bit. We're sending him the final songs to just add a little bit of programming to, or things like that.

Speaker 3 (00:51:45):

He would send over a harmony on a vocal part

Speaker 2 (00:51:48):

That he

Speaker 3 (00:51:49):

Built, that he forced with Melaine, something like that, and then he goes, try singing this way. So it's like he was producing the background harmony vocals from afar. So yeah, that was just a little interesting thing he would do.

Speaker 2 (00:52:03):

Totally. So again, he's still involved, but we're sort of slowly but surely taking more on ourselves. So the record after that, which would've been, let's see, where are we at? Outlive and then War and Peace, right?

Speaker 3 (00:52:18):

Yeah. Extre as Outlive, and then we're at War and Peace, which is the double, we released two records in the same day, but it's two records.

Speaker 2 (00:52:25):

Yes.

Speaker 3 (00:52:26):

Not a double record. It's two records.

Speaker 2 (00:52:28):

Yes. Okay. So that was the first time that Aaron wasn't a part of the equation at all. It's not because we were like, oh, we don't need to work with you anymore. It's hard to say why he wasn't part of the equation at that time, other than a lot of things had changed with his schedule, what he was doing at the time. He went from producing records and working with bands to doing more songwriting stuff and a lot of that sort of thing.

Speaker 3 (00:52:57):

Well, you answered it earlier, you said, now when I go into the studio, I have all the backgrounds already laid out. That's it. I mean, because before you didn't do it.

Speaker 2 (00:53:05):

Yeah, that's where I was going next. So having worked with Aaron Sprinkle for six records, the amount of tools that he gave me, just little tricks, whether it was structural things for the songs or little tricks to help even just something as simple as the tambourine and the chorus thing, which if you're listening really intently, you'll hear, especially on the more melodic songs, it's almost every song has a tambourine happening in the chorus. What it does is it just sort of brightens up the chorus and it makes it feel like a chorus. It feels like, boom, it's here.

Speaker 3 (00:53:45):

Sprinkle is a pop guy. So it's a pop move.

Speaker 2 (00:53:48):

It's a pop move. But it's also like, I hear it happening more often these days than I did when we were doing it back in the day. It almost seemed like, Ooh, is it a little taboo? Throw a tambourine in there? Is it a little cheesy? But it always felt right. It felt really good, felt bright, really gave us these choruses that felt like choruses and not just like metal bands starts to sing, which is a huge pet peeve for me because most metal bands that are considerably heavy that start singing, it's like there's just a singing part. It doesn't sound,

Speaker 1 (00:54:21):

It's a major pet

Speaker 2 (00:54:22):

Peeve. Yeah, it doesn't sound like a chorus. There's no hook. It's just singing. So it helped give us that edge. But that's just one example of a hundred little things that were sort of like sprinkle iss that I just gathered over the years. So now when I write a song or when I demo a song, I'm integrating a ton of that stuff that he sort of showed me. So if you listen to the demos, when I was the first couple of records, everything was just like cookie cutter. The first verse would be the exact same as the second verse, and everything would be flown and yada, yada, yada. Over the years, incorporating all these tricks. Second verse should have some sort of differentiation between the first and the second verse, just to keep things interesting so it doesn't seem like it's just a carbon copy. Little aspects like that. Or when you come out of the bridge and you're going back into that final chorus, which structurally is something we do a lot, there's got to be some sort of like, let's drop it out for a second. And you can do that in different ways. It doesn't always have to be music drops out and it's just vocal and acoustic or whatever. That's one way to do it. But there's a dozen different ways to do that. Those are just examples of stuff that, anyway, this is a long version of saying,

Speaker 3 (00:55:39):

He asked how you eventually started.

Speaker 2 (00:55:40):

Trust me, I'm getting there.

Speaker 3 (00:55:41):

I'm getting, and you're like, well, I write songs like this.

Speaker 2 (00:55:45):

I'm getting there by the time we did War and Peace. It's like, okay, so now Aaron's out of the equation altogether. Jeremiah's doing everything and now really the only additional thing we're doing at that point is mixing and mastering with someone else. So when it came time to do exile, it's like are we ready to take on the mixing aspect and do that and have Jeremiah do that as well? It's not the first thing that Jeremiah has ever mixed, so there is some proof there. He's mixed things. Before I knew that he was capable, I knew that we'd be able to work on it sort of ad nauseum if there was any sort of learning curve or like that for either of us. It was like we could just sit there and work on it like crazy. But I knew that he was absolutely capable of doing it. He's just as capable as any other engineer that I've ever worked with. So I knew that that was there and it was just a matter of the time and experience that we've had together. It's like, are we at that point now where we can bite this off and make this happen? And I knew that it was possible. We both did, but it was just like, let's go for it and see what happens.

Speaker 1 (00:56:53):

That makes perfect sense. So it just seems like the most natural thing in the world. And I think also the Aaron Sprinkle story, I think that as far as bands go, you guys worked with him longer than most bands ever work with anybody. Six albums is a lot.

Speaker 3 (00:57:12):

It was he produced and then two records mixed by a person and then two records or the mixing engineer was always switching.

Speaker 2 (00:57:21):

We would rotate and mixers

Speaker 3 (00:57:22):

And then when it got to me producing, we hit Zeus. But when we did Extremist, that was our first record with me producing and Zeus mixing. It was like, man, we love the way this sounds. It was like, so we didn't want to get rid of that, so we kept with it for outlive. So that's two. And then if we're going to keep up with the cycle of just, okay, let's go find another mix guy then. So yeah, we did vary. Yeah, you're right. The producer, we stayed with the producer for longer, but they were back in the day varying it with the mixing guy.

Speaker 2 (00:57:58):

Part of that is because, so the way that the band was formed from the very beginning was it was me and my brother were just kind of like, do this. We had just moved from Seattle training for Utopia broken up and we were like, let's just start this new band. We didn't really have all the pieces together to actually do this thing. So it was like, alright, I guess we could write the music. Aaron Sprinkle brother Jesse could play drums if and when we go on tour, we could cobble together a live touring version of this band. And it was, honestly, I worked at Tooth and Nail and Solid state at the time. It was like the band consisted of coworkers. John Dunn, who's still our bass player to this day, worked in the mail room. He worked his way up to a and r and signed August Burns Red and Emory and all these other bands. But at that time when we first toured, he was a mail room guy and Chris McCadden who had played in embodiment and Society's Finest and other band the famine. He was also a designer like me, and I ended up hiring him. He moved up from LA where he was living at the time, and I mean, again, it's just like we were cobbling together this band out of just grasping it, whatever was there in front of us. Being scrappy, making

Speaker 1 (00:59:07):

The most of your current situation.

Speaker 2 (00:59:09):

Yeah, exactly. So when we hit the studio with Aaron, we didn't really know what we wanted to do or what we were doing. We knew that we wanted it to be slick and we knew that we wanted hooks and we knew we wanted certain aspect of melody. We were leaning into machine head, fear Factory, Deftones, the sort of nineties roadrunner stuff, but also we weren't super good players. We couldn't riff crazy or do solos, and Jesse who was doing drums for us couldn't do crazy double kick or super fast stuff. So it's like take all those influences, throw 'em in a blender, and then play them by people who are just trained in hardcore music, which is basically, I stopped learning how to play guitar at 15 years old. So that's what came out, which ended up being sort of a very simple metal core influenced new metal kind of thing.

(01:00:10):

But what sprinkle added to it in those early days was something that was sort of new and refreshing, adding all the programming aspects that he did, just some of the cool electronic things and just treating the vocals the way on more of a, honestly, it sounds more like a pop vocal in a lot of the choruses than the way that a lot of metal singing vocals were treated back then. And so there were certain things, and this was honestly by virtue of he had never worked with a metal band at this point. He had produced a lot of records, recorded a lot of bands. He had never done a metal record, so he approached this the same way that he would've like an Amber Lynn record or an MXPX record or whatever. So it's just naturally going to come out a lot different. If we were to go to whoever Terry Date, it's sort of going to sound like a guy who does a bunch of metal records, but because Aaron was approaching it from not only a guy who'd never done metal bands, but honestly didn't really listen to metal music and that ended up working in our favor because it ended up giving us these sort of interesting, unique little aspects to play with that became a part of our sound.

(01:01:21):

This is a really long way of me saying for the first few records, he was sort of the fifth Beatle. He was sort of like

Speaker 1 (01:01:27):

That. He

Speaker 2 (01:01:28):

Was sort of another aspect to the band artistically that seemed like at the time, absolutely an integral piece. And as we moved forward as a band, a lot of those aspects that he brought into the fold became just sort of second nature for us. And I started writing that way. I started editing myself in ways that he would edit. By the time we had six records down, it's like, okay, we know how the chorus vocals are supposed to sound. We know how the blank is supposed to sound because we are a brand now we have, there's sort of a standards guide for what we're doing. That's the reason why we stuck with him for so long.

Speaker 1 (01:02:10):

So his fingerprint is still on it.

Speaker 3 (01:02:12):

And also Patrick and I started doing the Keys and the synthesizers and all that kind of stuff too, which is what was his initial input into the record. So there's also that We still keep doing that

Speaker 2 (01:02:26):

And honestly, Jeremiah and Patrick, when they're writing or when Jeremiah's producing, it's like there already is sort of a blueprint and it's not that they have to stick to exactly what that blueprint is, but it's like by the time those guys were writing for the band or producing for the band, there was sort of an established thing that we were doing. It's like we definitely want to evolve and both of these guys have helped us evolve massively. There are things that we do now with Jeremiah and with Patrick specifically that we could have never done 10, 12 years ago, and it's sort of really helped us stay fresh and it's the reason why I feel like our fans are going like, man, how do these guys get better after 20 years? No one's getting better after 20 years,

Speaker 1 (01:03:12):

But it still sounds like you. That's what's cool about it. I had just listened to the new record before this start to finish. That's one of the things that really stuck out to me is all the elements that if you think a demon hunter, you can kind of go down a list of what you would associate with that sound like hooks, simple, catchy riffs. It's like this brand of heavy that it's hard to explain, but when you hear it, it's like a certain amount of programming, like certain tempo ish. Not saying it's all the same, it's not. But there's definitely characteristics to demon hunter songs that if you heard enough demon hunter, you can totally spot them the moment they come on. What I noticed about the new record was just how much, I mean obviously, but just how much it does sound like everything you would expect from Demon Hunter, but new and fresh, which is really, really cool because lots of times bands who have an established sound will get stale, and I think that that's a real challenge to stay true to what you are, stay totally recognizable, but somehow evolve it at the same time.

(01:04:29):

That's actually way challenging.

Speaker 3 (01:04:31):

Well, when we first started to do this, I mean there's also that. There's always that, I don't know, man, you're not sticking to the exact same formula if you're going to be experimental fans might not like it or there's plenty, I mean of examples of where bands went a little crazy and a little wacky and then nobody really, it wasn't received very well. It might've been received better later on, but it wasn't what fans were expecting, so they kind of got grossed out. So we knew that going into this, and I don't even think we went full on as much as we could have either. We definitely went in this direction

Speaker 2 (01:05:09):

In the back of our minds, and again, we've all been, Jeremiah is the quote newest member, and that's 2012, right?

Speaker 3 (01:05:17):

I've been the band that sound 11 years.

Speaker 2 (01:05:18):

Yeah, 11 years. So he's the newest member, but he's 11 years in

Speaker 3 (01:05:23):

Not that new.

Speaker 2 (01:05:24):

Not that new and sort the brain trust of writing.

Speaker 3 (01:05:27):

Thank you.

Speaker 2 (01:05:28):

When me and him and Patrick are sort of writing and going through demos, an understanding and sort of an unspoken, there's some unspoken rules or unspoken understandings about the way that we write and the things that Demon Hunter does. When Patrick sends me a bunch of songs, I know that Patrick's capable of writing modern rock songs. I know that he's also capable of writing super technical metal. He knows that it needs to be in our wheelhouse, and so when he sends me 30 demos, which he does every record, they're all demon hunter style songs, and a lot of 'em are way more technical than stuff I could play or I could demo, which is awesome. And so you hear that come through in a lot of his songs. If the riff is riffy and sounds like it might be hard to play, that's a Patrick riff.

(01:06:19):

That's definitely not a me riff, but that's awesome because that's helped us evolve. But when we're writing, we all know that demon hunter is not like a Radiohead. We're not going to take a hard left turn at any point in the back of our minds, we're like, okay, can we tick the boxes of what would make us stoked? Like a continued stok, like every record, we're stoked to get into it. We're stoked with the outcome. We don't feel like we're treading water. Is that one thing that we can tick at the same time? Can we tick the box of will fans be stoked by this? Will they be thrown for a loop? Will we be alienating anybody? When Jamie Josta once said, when you go to McDonald's, you don't want Taco Bell, you want McDonald's, you want what you're used to when you go to McDonald's.

(01:07:01):

So that's probably more true for hate Breathe than it is for us, but there's a certain aspect of that that I do think is important. When you give someone a new demon hunter, do you want to give them kid A and have everyone scratching their heads, which it can work for a band, especially a band that at a certain point is sort of known for making those hard left turns. David Bowie was like that. Every record was something totally different. That becomes a thing and it becomes something that people come to expect and be excited about, but for us, there's a certain aspect or a backbone or a blueprint of it should sort of sound like this. Now, the good thing for us is since record number one, we've given ourselves a pretty big playground because we have these ballad esque songs. We have these mid tempo songs.

(01:07:48):

We have songs that are entirely singing. We have barn burners that are entirely screaming, and they're like, punk beats those two sides of the coin. And then everything in between that we get to play with. A lot of bands don't give themselves that opportunity or those sort of rights right out of the gate, no pun intended, but at the gates, it's like when at the Gates does a record, it's going to sort of primarily sound, the songs are going to basically be the same with the exception of one or two acoustic instrumental tracks. Right? That's not

Speaker 1 (01:08:18):

And that's what you want out of two.

Speaker 2 (01:08:20):

Exactly. That's the McDonald's that right? That's the two cheeseburger meal that you want when you get at the gates.

Speaker 1 (01:08:25):

Yeah, no, honestly, if at the gates put out something that wasn't a style, I'd be like, what? Yeah,

Speaker 2 (01:08:31):

If Limberg started singing, trying to do hooks, we would all be put off by it as we should, but it's like demon hunter. We were already giving ourselves this really big playground to play in. So that not only keeps things interesting for us, it's just easier for us to evolve over the years because we have this massive area to play in that is still, at the end of the day, innately demon hunter to do so it's not going to, we can do a record that is maybe more melodic than the last one, but it's still going to sound demon hunter. Or we can do a record that's more maybe primarily a heavy record. True Defiance was almost one of those records where it was like, oh, this is actually a lot of heavy stuff and outlive was as well, we can do that, and it's not going to throw anyone for a loop. It's just like, oh, this is a heavier demon hunter record than the last one.

Speaker 1 (01:09:19):

The thing about it though that I really respect is the ability to respect your own brand while also keeping it artistically honest. There's this weird misconception out there or this weird idea, I feel like sometimes where if you use the word brand with a band or you talk about having not rules, but boundaries or something, sometimes people will think that that means that you're going to come up with something contrived. I think just the opposite really. I think that limitations breed creativity. I do think though that sometimes people will get the wrong idea about that, where I really, really respect it when bands know exactly how to stay true to who they are, yet you hear their music and it's just as honest as it ever was.

Speaker 2 (01:10:15):

I think the problem with using the word brand for a band is a band should be at the end of the day, in its truest and purest form. It should be highly artistic. And when you say a brand, it sort of sounds corporate when bands or band guys or musicians or when people like us hear those kinds of words, were sort of put off by the corporateness of those words, but it really does a better job of explaining a whole bunch of things that would be hard to put into words.

Speaker 1 (01:10:42):

What else would you call it?

Speaker 2 (01:10:44):

And whether or not Seager Roast would call what they do, like a brand. It is a brand. You create a brand by virtue of the sort of look and feel and the aesthetic and the overarching themes and all those sort things are just sort of feeding back into what you could call a brand, whether you like it or not. Radiohead can sit there and pose for photos and look like they're put out the whole time, oh, they don't want to be here in these photos. But at the end of the day, that actually becomes part of their brand. They look like dudes who don't want to be there. Oasis was the same thing. It looks like guys who can't be bothered, but that becomes part of your brand. Even if you're trying to work against the brand, it sort of becomes your brand at a certain point. It just, Mastodon sort of has a humorous edge, whether or not they're just trying to make light of things or take things less seriously than the average metal band. At the end of the day, it becomes part of your brand whether you want it to or not. It's just like, are you willing to use that word?

Speaker 1 (01:11:45):

Yeah, I mean, I think you should just call it what it is. I mean, that is what it is.

Speaker 2 (01:11:50):

And for me, I work in design and it's just part of the vernacular. It's what I do with most of my time, so it just makes more sense for me to see it that way.

Speaker 1 (01:12:00):

Yeah, totally. Jeremiah, question for you. You said in the pre-interview actually that an old band of yours, junior high or something, you went to record at a local studio for about $500 a

Speaker 3 (01:12:15):

Day,

Speaker 1 (01:12:16):

And engineers seemed kind of disinterested in doing what you guys wanted sonically. That was kind of your jump off point in engineering. What I thought was interesting about that is that I feel like most people in heavy music that are 50 and under, that's how they started, is they went to a studio, some local studio that was overpriced and some engineer didn't get it or didn't want to get it,

Speaker 3 (01:12:46):

Didn't get it, is the big point there.

Speaker 1 (01:12:49):

And that led to almost every awesome producer in heavy music started that way. So when I read that from the pre-interview, I was like, yep, I know that story. Well,

Speaker 3 (01:12:59):

It keeps going today, so if I think it should be this way, and I hear it this way in my head, and then you go to a professional or somebody to do something, and then they don't do it that way, and then I push 'em aside and go, I'll just do it myself. And then that's why here we are later on doing everything about the record, even having the label ourselves. So we'll just do it. We'll just do it. But it all goes back to even when I was, like I said, I was like, what, 15, 14 or something, but somewhere in southeast Texas. Yeah. I mean, I think it was like, well, how'd you get into it? I mean, I loved guitar and playing in bands. I was loving every single new little thing about it when it was like, oh, I play guitar.

(01:13:47):

Oh, I'm in a band. I love this too. Oh, wow. Doing long road trips to some stupid gig that no one's going to show up to. I love this too. I love the road trip part. Okay, and then recording. Oh wow, I love this. Oh, wait a minute. This isn't going well. And I just remember seeing the guy, and I wasn't overwhelmed with the console. I mean, I recognized really quick that it's just lines of the knobs and it's the same thing from left to right. It's like one little strip, all of them. And I'm watching his fingers, and it was like we wanted a no effects kick drum sound, right? We played it for him, and he just kind of rolled his eyes and brushed us off and it was like he was just getting this, I dunno, a blues rock kick drum sound. And it was like, no, dude, eq, it better do something. You're the engineer. And then he was like, no, this sounds good. And he was kind of fighting us on it. So that moment I was like, dude, if I'm watching him play with those knobs, I know what to do now.

(01:14:49):

If we can knock this dude over the head and just drag him outside, I'll touch those knobs and I'll make that kick drum sound better than he does. And so it was kind of like, I think I could do this. Yeah, I'm going to learn how to do this. We're never going to come back to this guy ever again. I'll learn something. It took years to get anywhere, but that gave me the, oh, I do like the engineering part of it. And then also I also learned, man, you got to listen to your artist. You can't just like, ah, you don't know what you're talking about.

Speaker 1 (01:15:15):

You got

Speaker 3 (01:15:16):

To listen to them.

Speaker 1 (01:15:17):