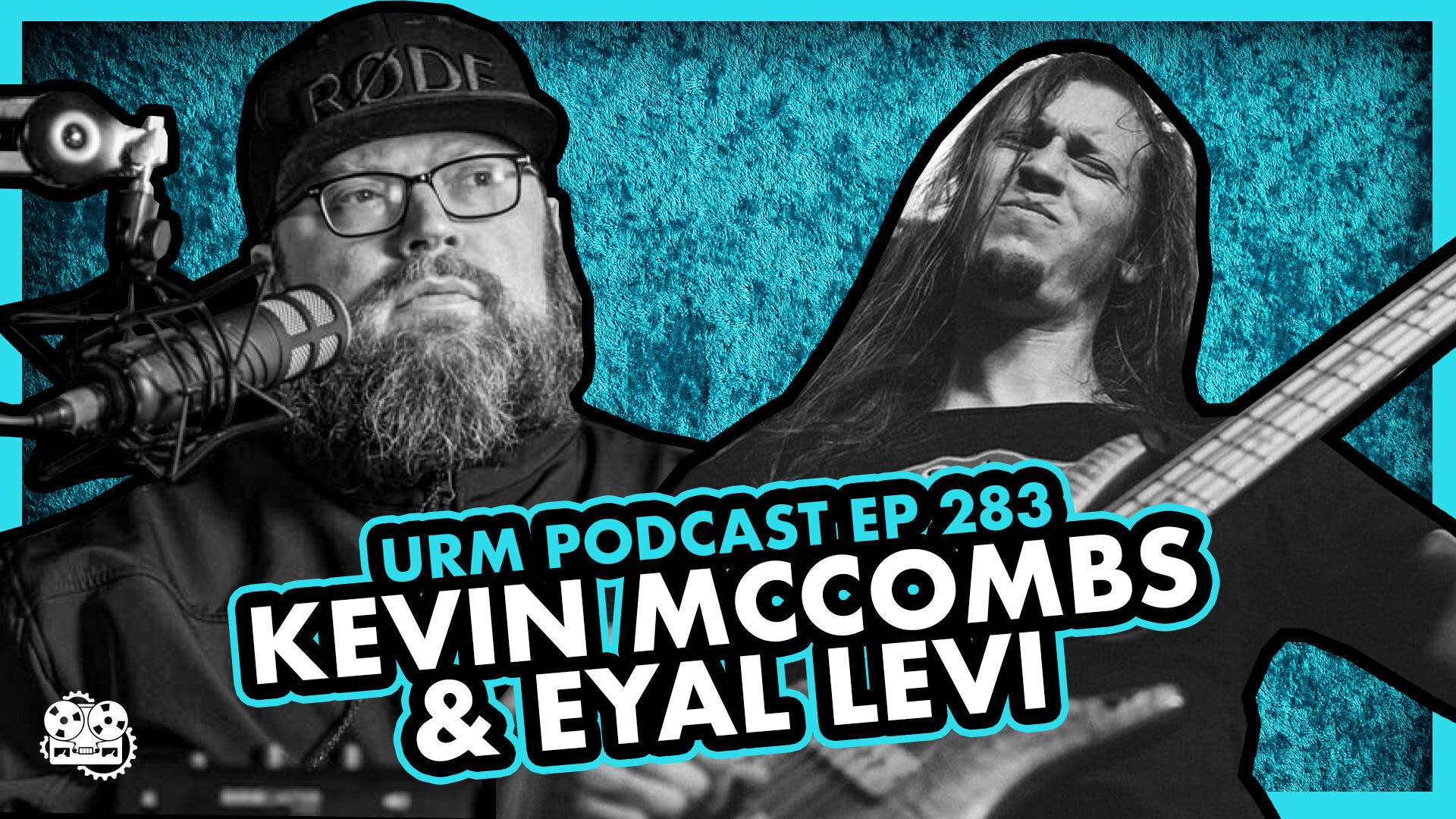

KEVIN MCCOMBS: From a Small Town to Major Labels, The Assistant Hustle, and Proving Your Value

Eyal Levi

Kevin McCombs is an engineer who made the leap from running a local studio in Jacksonville, Florida to working on major label records in North Hollywood, California. A former URM student, he now works alongside producer Colin Brittain, with engineering credits for artists like A Day To Remember, Papa Roach, 311, Ashes to New, and Dreamers.

In This Episode

Kevin McCombs shares the incredible story of how a single phone call from Eyal Levi landed him an assistant gig on an A Day To Remember session, forcing him to drop everything and move to LA. This episode is a must-listen for anyone grinding it out in a small town and wondering how to break into the big leagues. Kevin gives a raw, honest look at the mindset required to succeed, from knowing when to shut up and just be useful to the intense pressure of your first high-stakes session. He breaks down how he proved his value by doing whatever was needed—soldering pedals, building shelves, taking out the trash—and how that trust allowed him to graduate from assistant to engineer. It’s a deep dive into the real-world hustle, the importance of loyalty, and what it’s actually like to see how records you hear on the radio get made from the ground up.

Products Mentioned

Timestamps

- [3:50] From running a local Florida studio to working on major projects

- [5:21] How Eyal recommended Kevin for the A Day To Remember session with Colin Brittain

- [7:58] Having to call all his clients to cancel jobs for the new opportunity

- [14:00] The first day on the job and a near-disaster with a room mic stand

- [17:35] The staggering realization of what real, high-level production looks like

- [19:42] How Eyal’s “How Not To Fuck Up Your Audio Career” talk was his bible

- [20:52] An incredible example of what an assistant should NEVER say

- [22:24] The immense pressure and stakes on major label sessions

- [26:13] Making himself useful beyond audio: soldering pedals and building shelves

- [32:22] How trust is built by mastering menial tasks

- [35:19] The insane pressure of being asked to tune a guitar for Colin Brittain

- [39:47] The conversation that led to him moving to LA

- [42:20] The culture shock of moving to LA and leaving his old life behind

- [55:27] The importance of loyalty in the music industry

- [57:16] A day in the life as Colin Brittain’s full-time engineer

- [1:05:15] Advice for producers feeling stuck in a small town

- [1:09:56] The right way to ask for opportunities: “How can I provide value?”

- [1:16:17] Seeing a true Pro Tools master at work and realizing how high the bar really is

Transcript

Speaker 1 (00:00:00):

Welcome to the Unstoppable Recording Machine Podcast, and now your host, Eyal Levi. Welcome to the URM podcast. Thank you so much for being here. It's crazy to think that we're now on our fifth year, but it's true, and it's only because of you, the listeners, and if you'd like to see us stick around for another five years, there are a few simple things that you can do that would really, really help us out, and I would be endlessly appreciative. Number one, share our episodes with your friends. If you get something out of these episodes, I'm sure they will too. So please share us with your friends. Number two, post our episodes on your Facebook and Instagram and tag me and our guests too. My Instagram is at al Levi urm audio, and let me just let you know that we love seeing ourselves tagged in these posts.

(00:00:55):

Who knows, we might even respond. And number three, leave us reviews and five stars please anywhere you can. We especially love iTunes reviews. Once again, I want to thank you all for the years and years of loyalty. I just want you to know that we will never, ever charge you for this podcast, and I will always work as hard as possible to improve the episodes in every single way possible. All I ask in return is a share post and a tag. Now, let's get on with it. Hello everybody. My guest today is somebody that I am very, very proud of. He's been on before. I'm glad that he got to come back. His name is Kevin McCombs, and he's an engineer based out of North Hollywood, California. He's a longtime URM student who's gone from working in the aerospace industry to being a local studio owner in Jacksonville, Florida to engineering major label records with producer Colin Brit.

(00:01:52):

Since moving to California, Kevin has worked with bands like a Data. Remember Papa Roach, three 11 Dreamers and many, many more. I've watched this kid go from literally kind of nothing, just a talented URM student to being a real player in the real game, and I couldn't be prouder of him. Those of you who are listening, who are thinking to yourselves, I live in a small town. I don't live in la, I don't live in Nashville. I don't know how I'm going to do this, but I want to do this. This is an episode for you because this is the story of someone who was in your shoes, who is now living the dream. I introduce you, Kevin McCombs. Kevin McCombs, welcome back to the URM Podcast.

Speaker 2 (00:02:37):

Thank you so much for having me.

Speaker 1 (00:02:38):

Yeah, it's a miracle that we're doing this, isn't it?

Speaker 2 (00:02:41):

Yeah, we were. Oh, for three fourth times the charm, I guess.

Speaker 1 (00:02:44):

Yeah. This is officially the most times that I've had failed podcast attempts for one episode the most before was two. Well, it's an honor,

Speaker 2 (00:02:56):

Truly.

Speaker 1 (00:02:57):

I thought today was going to be shot as well when Skype started acting up,

Speaker 2 (00:03:02):

But we persevered, but here we are. And here we are.

Speaker 1 (00:03:04):

That's right. That's the motto here is persevere. What it's been like two months that we've been trying

Speaker 2 (00:03:10):

Yeah, since the beginning of this quarantine basically.

Speaker 1 (00:03:13):

Yeah. And right now it's what? June 6th?

Speaker 2 (00:03:17):

It is the seventh. Seventh, which is coincidentally exactly two years from the first podcast that we did.

Speaker 1 (00:03:24):

It is.

Speaker 2 (00:03:25):

It is.

Speaker 1 (00:03:26):

Well, happy birthday.

Speaker 2 (00:03:27):

Oh, thank you.

Speaker 1 (00:03:28):

Well, lots changed in two years.

Speaker 2 (00:03:30):

It has, indeed.

Speaker 1 (00:03:31):

You hadn't even moved to LA yet, right?

Speaker 2 (00:03:33):

No, I had just started my local Florida studio At that point, I had just made the jump to full-time.

Speaker 1 (00:03:40):

That was only two years ago.

Speaker 2 (00:03:41):

That's correct,

Speaker 1 (00:03:42):

Man. Things have changed.

Speaker 2 (00:03:44):

Yeah.

Speaker 1 (00:03:44):

So at that time, did you foresee anything that came next?

Speaker 2 (00:03:50):

Not really. I kind of fully expected to grind it out by myself in Florida for a very long time and try to build what I could out of Jacksonville in a local music scene and try to climb my way up getting bigger and bigger projects. But it all kind of changed at once when I got a phone call from Papa Al. So

Speaker 1 (00:04:09):

Yeah. I'm glad you didn't embarrass me.

Speaker 2 (00:04:11):

Yeah, no kidding.

Speaker 1 (00:04:13):

Yeah, I just got to say thank you. Whenever I vouch for people, it always fills me with dread. It's one of those things where especially with recording schools, when they try to get people into gigs, my experience is that everyone that they send me is useless. And I know that that's the same experience that all my producer friends have. So I have this personal thing where if I make a recommendation to somebody about a person, especially about a person, then it's got to be legit because I don't ever want to inhabit that same sort of space that the recording school internship departments inhabit basically.

Speaker 2 (00:04:59):

Not only that, but you lose your power of recommendation.

Speaker 1 (00:05:02):

That's what I'm saying.

Speaker 2 (00:05:03):

Yeah.

Speaker 1 (00:05:04):

Obviously if you recommend someone, they turn out to be useless. It's not a hundred percent on you, but you still vouched for them and they're not going to ask you again in the future. I dunno. So thank you for not fucking

Speaker 2 (00:05:19):

Up. My pleasure.

Speaker 1 (00:05:21):

Yeah, I just had to say that. So let's talk about what went down for people that are unfamiliar with the story, because the story is really cool. I think. I'll tell you my version and then I want to hear yours. My version is that Colin Brit was in Orlando working on a data, remember? And he was basically burning through interns or something like that. For people who don't know, Colin is based out of LA and he brought his rig to the audio compound in Florida and his No small thing, and it's not really something that one person can operate and really do a good job producing as well. It's one of those situations that you need a producer, an engineer, and then also intern assistance. It's a serious rig, and he brought Rick Carson with him as an assistant engineer or engineer as an

Speaker 2 (00:06:21):

Engineer

Speaker 1 (00:06:21):

Who engineer who's been on the podcast twice who's brilliant, but didn't bring anybody in the intern slot or assistant slot, I believe. So was taking recommendations from some of the local recording schools, won't name names, but ones in Orlando that are really big and it wasn't working out, and he called me really late one night and was like, I'm at the end of a rope right here. I need help on this record. What do I do? Do you have anybody? And immediately I thought of you, Kevin, and the reason I thought of you was, well, there were a few reasons. One, you had made a really good impression on me several times as just somebody serious. Two, I had already featured you on the Career builder promo shows and stuff that we were doing as someone from the URM community who was doing well, and three, you were in proximity like an hour and a half away.

(00:07:25):

So I bet you this could work out, maybe it won't. Kevin's like a serious metal dude, but let's give this a shot. And I remember calling you or texting you or whatever, and you were in the middle of working with a band, and if I remember correctly, the thing I said was, call in needs help on a day to remember, can you be there tomorrow? And your question was, if this works out, what do I do with the band I'm working on? And I believe I told you, stop working on them or something like that.

Speaker 2 (00:07:58):

Yeah, effectively, I made some phone calls to the people I was working with and everyone else on my schedule and I said, Hey, I will issue refunds if you guys want 'em. If you want to wait for however long this takes for me to have this radical studio experience, then I would love to finish these projects. But right now I think I have to do this. And everyone was super cool about it. I was able to go down there and not burn any bridges in the process, which was very nice, but certainly is not required of an opportunity like that. It doesn't always pan out like that.

Speaker 1 (00:08:34):

No. As a matter of fact, I think that you lucked out in that you didn't burn any bridges. I think it's entirely possible that someone could have been a diva and been like, no, you've got to stay here and finish our record. You can't go take this massive career opportunity. Fuck you, Kevin.

Speaker 2 (00:08:50):

It's nice too because

Speaker 1 (00:08:51):

Yeah, fuck you,

Speaker 2 (00:08:52):

Man. Yeah, it's nice too because it's with a Florida band that everyone in my scene respects and likes. So I said, Hey, I need to go work on a day to remember. They were like, yeah, go. What are you doing here?

Speaker 1 (00:09:05):

That's great. That makes it a lot easier. What's interesting, this reminds me, you're not the first person I've ever recommended for a gig. I have a long history of doing it. I got Ryan Knight into ais who then got into Black Dahlia, and I have a long history going back, 15 years of recommending people. And one thing that used to come up a lot, I haven't encountered it in a while, but it's just a funny, interesting note, is I would recommend people that I thought were really awesome who were in local bands. Like Ryan for instance, he was in a band called The Knife Trade. He was already an incredible guitar player. It was clear that he belonged somewhere, not better. The knife trade was good. They just weren't going anywhere, honestly. And when I got him the gig or the opportunity, he was afraid to leave his local band. And that happened several times when I would recommend people that were really good, they had something going locally and just sometimes they didn't follow through on the recommendation just because they didn't want to upset their local friends. Bummed me out a little bit

Speaker 2 (00:10:22):

With my own local band. I had a heart to heart with the other members of Criter, and I said, look, this is huge. Potentially if I do what I'm supposed to do, there's no guarantees. But working on a project like this, there's no way that I won't get better at making music, that I won't get more skilled as an engineer. That any of the things that I learned won't help any project that we might do in the future. And again, the response was run, do not walk towards this opportunity.

Speaker 1 (00:10:53):

That's awesome. That's great. Again, it's surprising. That's also what I used to tell people is if people in your band are weird about it, they might be weird about it at first because it's a shock, but if you reason with them, there's no reason for why they should have a problem with it because all that's going to happen. Whether it's you getting with Colin or somebody getting into a bigger band, it's like you're going to get a bunch more contacts. You're going to learn how everything's done, and if this project stays together, it's only going to benefit as a result. And I think that most reasonable people would understand that. Absolutely. So what happened then? Tell me about it from your perspective.

Speaker 2 (00:11:36):

So following that phone call,

Speaker 1 (00:11:37):

Well, let's start with the phone call. What's going on when I called you? And then what was it like on your end?

Speaker 2 (00:11:44):

It was interesting and very timely that I got that call from you because I had been in talks with my mentors and friends literally that week about sort of feeling like I had plateaued a bit after having run my studio for a full year and not really knowing what to do if I should seek an internship or I don't even think audio school or anything like that was on my mind, but I needed to do something to get out of stagnation and keep pushing myself. And lo and behold, I received the phone call from you. Serendipity is the only word that I can use to describe the situation, but I got the call and then I wiped my schedule. I called my close friends and family and I said, look, I got to do this. Something really significant just happened, and I knew that it could be a sort of fork in the road for an entire career in professional audio, not just audio, but working in the music industry as opposed to just working with local clients and getting people to trust you with their art

Speaker 1 (00:12:45):

In the actual industry.

Speaker 2 (00:12:46):

That's right. Dealing with labels and a and r and stuff that I had never come in contact with, even remotely. So the expectation was, okay, punk, if you want to do this show up, be in Orlando by 9:00 AM the next morning. And so I did, and following the phone call with you, you put me in contact with Rick Carson, who it's the engineer's job frequently to sort of vet potential assistance. And he called me to fill me out and see if I was a schmuck and if we were going to have a good time together, making a really serious record. And somehow I managed to not rub him the wrong way. And then I met him the following morning, and then me and Rick became quick friends hanging out with the Aded. Remember crew, I spent most of my time working with Rick in the back. If Colin's cutting a vocal or something like that, it's him alone in the room with an artist. And so there's a lot of downtime where a lot of people still need assistance or things are still happening on multiple fronts. So I spent most of my time hanging out with Rick Carson and getting podcast level wisdom from him on a daily basis. That was a really formative experience for me.

Speaker 1 (00:14:00):

Let's talk about the day that you showed up. I believe that we spoke in the evening, right?

Speaker 2 (00:14:05):

That's correct.

Speaker 1 (00:14:06):

Yeah. So you had less than 12 hours or something to figure it out and be in Orlando. So you showed up and then what?

Speaker 2 (00:14:14):

I showed up early, the audio compound was not yet open. Rick rolls up from his Uber and then opens the door, and then I think the other assistant who was there just doing sort of clerical stuff, food order, a runner basically. He kind of showed me the ropes of like, Hey, this is, take the trash out, do it. Here's the mundane tasks required of you every day. I said, okay, no problem. And I started to do some dishes and whatever. And then on that first day, the first sort of real opportunity that I got was, Hey, we need room mics. Can you get these AKGs up on some stands? I said, yeah, yes sir. And I went in there and I started to get 'em on stands and I noticed that the linkage that connects to the mic stand required a flathead screwdriver to adjust.

(00:15:11):

And I was like, oh crap. I'm in a studio where I know where nothing is and I need to quickly find something, a quarter, something I can stick in there to adjust this properly and get it on there as fast as I can and searching. I'm freaking out. I'm like, oh man, this is bad. And Rick comes in and he goes, man, what has taken so long? And I explained the situation and he goes, bro, check this out. And then he takes the clip and he flips it the other way and it's just correct. I thought it was the end. I could tell he looked at me like, this is the dude. Are you sure that was strike one? And I knew that, but luckily later on that day, had to drive Rick around for an errand and we were able to have a heart to heart where he was sort of probing and figuring out what I wanted to do in life, what I wanted to do with music.

(00:16:01):

And somehow after that conversation, he went to Colin and he said, Hey, this kid's serious. He actually wants to do this. It's not somebody who's just looking for the credit. It's not somebody who's looking to get paid for anything. He wants to put in 16 hour days to make records because he's a crazy person like we are. And after that, that's exactly what it was is I was working with Rick, I was working with Colin, I was working with the band, and I was there every single morning before anyone got there and I was there with Rick, well after everyone left every single day, and that went on for two months and I wasn't sleeping much, but I was just running on pure stoke the entire time. And yeah, just the things that I'd get to see, I wouldn't be invited into the control room until late at night when Colin was just working on additional production or tracking some additional guitars or what have you.

(00:17:00):

Obviously a number of people would have to leave the room before I was allowed in there to just sit quietly. The first time I kind of got to be in the room and see what actual production looked like, what it looks like to take a song that was just an arrangement and build it up one layer at a time until it was something that you'd hear on the radio and I'd never seen that before. Certainly I've had access to multi-track files and stems and things like that to see what it looks like after it's in a session, but seeing things come together sort of X neo low, it kind of changed me.

Speaker 1 (00:17:34):

How so?

Speaker 2 (00:17:35):

It made me realize I had no idea at the time. I was a local studio owner and I called myself a producer, and then in that moment I was like, oh, I'm not one of those. I'm not one of those at all and I'm still not. It's going to be years from this point even if I ever become one because of what I've seen. I saw where the bar actually was. It's pretty

Speaker 1 (00:18:00):

Staggering when you see it for the

Speaker 2 (00:18:02):

First time. It was almost disturbing because Colin works fast. He's very fast, he operates cubase, kind of like an extension of his body. He's very musical and his actions, even editing and stuff like that, he's just flying through it. He's ripping.

Speaker 1 (00:18:18):

It's interesting too because he likes to come off as though he's not technical, but he's technical as fuck.

Speaker 2 (00:18:24):

Yeah. And then he'll turn around and he'll offer some explanation unprompted for what he's doing. He has pretty intense knowledge that he's gotten from other people that he's gotten from trial and error of the technical side, but he's so creative, he'll trick you into thinking that he's flying by the seat of his pants. It was really cool to watch and I think it kicked my ass a lot to see that. And not only that, but I was working on a session that was so high level that even though I had been working on local stuff in some capacity for a few years, every aspect of what was happening was so high level that I could not contribute and that's why I was an assistant. That's why I took out the trash. That's why I scrubbed toilets and I did all of that stuff because my ability to contribute to a session like that has everything to do with what just needs to get done.

Speaker 1 (00:19:17):

What's interesting that they say about when you first get an internship or an assistant gig is knowing when to shut the fuck up. One of the biggest faux PAs that a new intern can do is to speak up when they're not supposed to. And so I think the fact that you realized I'm a little bit out of my league here, let's not stand out in that weird way. I think that was really smart.

Speaker 2 (00:19:42):

Well, I wasn't unguided because I had a notebook full of notes from the first summit that were kind of guiding me. Not to brag on you Al, but your advice from the talk that you gave at the first summit was my Bible in the moment and your talk was entitled How Not To Fuck Up Your Audio Career.

Speaker 1 (00:20:05):

People thought that that was just a funny title, but it was a hundred percent serious.

Speaker 2 (00:20:10):

No truer words have ever been spoken to me.

Speaker 1 (00:20:13):

It was short too, I believe

Speaker 2 (00:20:14):

It was.

Speaker 1 (00:20:15):

Yeah, it's a was a short presentation. No bullshit. Just exactly how to not fuck up the end.

Speaker 2 (00:20:22):

Yeah. Lucky for me, I think by nature I'm kind of a quiet person and I like to listen in general and read the Room as it's put in this industry is that you have to read the room, you have to have a good sense of what's going on and what's appropriate to say if it's even appropriate to say anything. A compliment that I was paid fairly early on is just that I was quiet and I was useful.

Speaker 1 (00:20:48):

There's no higher compliment

Speaker 2 (00:20:50):

For an assistant. Absolutely not.

(00:20:52):

And it's what I've come to expect of people that I look for when I bring in a runner or someone like that to a session that we're working on out here in LA is, man, if I want to be able to trust this person, I got to know that they're going to be quiet. They need to be briefed If they have not received the briefing of Al and yeah, it only takes one wrong thing to get kicked out of a session and never invited back. I've seen that too recently. We were working on a pretty serious record. The assistant that I had gotten on a recommendation from a mutual friend because our usual guy was unavailable. He came in and he was in the control room and we're trying to nail this bass tone and Colin will turn to me, do you think it needs more or less gain or we're having sort of discussions back and forth between the artist, the producer and the engineer, and then the assistant speaks. He goes, yeah, tonally, I think it's there, but the vibe's not right.

Speaker 1 (00:21:52):

Oh man,

Speaker 2 (00:21:54):

I received a stink eye I have never received before, which said, Hey, get your boy. That one was dealt with swiftly, but if you need an example of what not to say, that's it.

Speaker 1 (00:22:05):

It's like who asked? That's the thing who asked him his opinion

Speaker 2 (00:22:09):

Questions happen generally in a control room and as an assistant, they're not directed at you ever.

Speaker 1 (00:22:16):

Yeah,

Speaker 2 (00:22:17):

Yeah.

Speaker 1 (00:22:18):

Unless they're specifically directed at you.

Speaker 2 (00:22:20):

Right. When that happens, be careful what you say.

Speaker 1 (00:22:24):

What's interesting is on the surface, I think maybe to someone who's not in these sound like some seriously asshole rules, but once you're in it, you understand why they're there. For instance, when you're working with an artist, high level or any level, but especially high level, there's a lot on the line. It's not just the artist's career. It's not just that they're being an egomaniac. They have their family, they have the other band mates, they have a label. The label has employees, they have management, the manager has employees. There's a booking agent. The booking agent has employees, the band has its crew. There's a whole ecosystem around this band and whether or not what you're doing in the studio there does well that kind of determines if these people are going to be employed for the next two years. There's kind of a ton of pressure on it.

(00:23:21):

And so when an artist goes to a producer, they're not just trusting them with their art, they're trusting them with their livelihood, and for someone who is unproven and it's just a stranger to start imposing their viewpoint on something that's so sacred, it is just out of line and it breaks the vibe and it makes people uncomfortable and it just shouldn't be done. It's one of those know your place things, and if someone doesn't understand that from the get go in that type of situation, how are they going to be able to resolve real conflicts down the line when they have to make real decisions? If they can't read the people that they're working with and don't understand what's at stake or what everyone's role is, how can they be trusted to handle a project that so much relies on?

Speaker 2 (00:24:20):

It's not only that, but a thought that I have kind of constantly is if you feel compelled to contribute anything to the situation, consider the fact that the room is filled usually with a small number of people and every single person in there in some capacity other than you, the assistant has worked on and been a significant part of music that has captivated millions of people. If you have never done that once in your life, I don't think that your opinion on whether or not the verse should be half the speed is really going to. There are times where my internal monologue is going, oh man, it'd be cool if this happened, but I also know not to say those things because I've never written a song myself that has captivated millions of people. I'm not an accomplished songwriter such that my opinion would hold weight with a room full of people who do it every day.

(00:25:15):

It's just strange because the role of the assistant is one where it is a very serious opportunity, but it's got nothing to do with you. And the biggest opportunity I ever got in my life, I could have been anyone. The fact that I didn't fuck it up meant that things went well, but it didn't have anything to do with me. My name might end up in the fine print of an assistant credit on a record like that, but for the most part, nobody cares that I'm there. It's not important. What's important is that the things that I needed to do got done.

Speaker 1 (00:25:48):

Let's talk about that. So you were saying earlier that you felt like you couldn't contribute, but I mean you didn't mean that in a bitchy way, it's just No, not at

Speaker 2 (00:25:59):

All.

Speaker 1 (00:25:59):

Yeah. You knew that in some ways you're stepping into the big leagues. So how did you contribute? What were the things that you did do to make yourself valuable or useful?

Speaker 2 (00:26:13):

I did anything that was asked of me, or if I saw that there was a problem peripheral to the session within my means to fix, I took it upon myself to offer. So having experience in the aerospace industry and with technical wiring and stuff like that, there was a lot of tinkering going on in the back of the warehouse where guitar pedals were being built and a Marshall was being wired by hand by Neil Westfall, and I said, Hey, man, I can help with that. They said, really? I was like, yeah, lemme get in here and I'll solder together a few of these buttons or anything that gives you trouble. Let me know and I'll help you out. And they were like, dope. This is something that's useful, even though it has nothing to do with the recording that's right in front of us, but it's a way to contribute to people that you're hanging out with on a daily basis and just not being a bummer in general. And so I found myself fixing a lot of things that I could within reason that they needed a shelf in the back room, so I went to Home Depot, bought a bunch of wood, and then it helped them build one and painted it. Part of the trick of being effective at this is not thinking that you're above any task, is that if you're capable of doing it and it needs to get done, then widen it done yet,

Speaker 1 (00:27:36):

It's a good way to look at it.

Speaker 2 (00:27:37):

Their entire crew came in at one point for rehearsals, so they have guitar techs, two of them that are working and they're rehearsing in their space and they got the in-ear rig and all of these things basically simulating an entire show and there's guitar changes and all of these things happening really fast, and so in the moment, they handed me a set of ears so I could listen to what was going on, and I was working on guitars, screwing in straps, doing really basic stuff, but one of the guitar techs turned to me, he goes, man, things are easy when you're here and no higher compliment can be paid to someone whose job it is to just make everyone's life easier. That's really what you're there to do is hunger is a problem. You can fix that by going again. Food. Being tired can be a problem in the studio. Coffee's a good fix for that. Figure out what people like and don't be a huge pain in the ass when you ask them about it, the least that they have to think about your presence, the better. If things just show up, they don't even have to know that you did, but if things are just easy, if people feel like they're in an environment where they can be relaxed and not stressed out about small details, then that job is being performed valiantly.

Speaker 1 (00:28:56):

People do notice that life is easier when you're around and it's something, it takes a little bit of time, but if they just notice that the sessions run better for whatever reason, they will attribute that to your presence. They don't need to keep score of every little thing you've done.

Speaker 2 (00:29:14):

Certainly not,

Speaker 1 (00:29:15):

Even though I think people like Rick are keeping score,

Speaker 2 (00:29:18):

Certainly he is. As a smart dude,

Speaker 1 (00:29:20):

I keep score. I keep score of that kind of stuff. Even if I don't tell people, I'm always keeping score on stuff like that. And it's interesting you just said, don't be above any task. I think a lot of people who go for internships and assistantships, assistantship, is that even a word? A lot of people who go for those positions, I feel like they feel like they're above certain tasks. They're too good for certain things, or they won't put themselves out there. Maybe they'll do the basic rounds of shitty tasks that they're given, but they won't do extra ones because the goal is to be done doing the shitty tasks as quickly as possible, which I think is a serious mistake.

Speaker 2 (00:30:02):

Absolutely.

Speaker 1 (00:30:03):

Yeah. Yeah. Those shitty tasks are going to continue to be a thing. Those little things, they don't seem like a big deal when you're looking at each one as an isolated incident. Maybe there's a little bit of a mess in one room and coffee is needed and people need food, and this one wiring on a jack came loose and all these things, they start to add up, and if you're kind of handling all of those things, people do notice that overall things are just smoother, but if people don't make it like their mission in life to solve every single one of those as they happen or even before they happen, I think people notice that they're not necessarily in it to win it. You know what I mean?

(00:30:54):

When I've had people working under me, I can tell if their heart and soul is in making this a better situation for everybody. For instance, with Nick, he was like that before we hired him. I remember he was like Andrew Wade's assistant, and he wanted to work for us. We didn't know him. I mean, we had met him through Andrew, but we didn't know him or anything, and he took it upon himself to basically prove that we should hire him, and I don't think he had told us that he wanted us to hire him. He just showed us, and so he did certain things. For instance, we did nail the mix in Nashville. He asked if he could help out on it, and he drove himself to Nashville at his own expense and just showed up to the sessions early and just did things like took note of what everybody's drink preferences were, and then they just were at the studio the next day when we showed up. He paid attention to what everybody's dietary issues were, and the food just magically appeared like he was down to do anything possible, and he just did that over and over and over again until we were like, shit just runs better when this kid's around. Let's have him around more. It's really that simple.

(00:32:20):

Dealt with the opposite too.

Speaker 2 (00:32:22):

What's important about that too is just that's how trust is built. If they can trust you to handle menial tasks and you just knock it out of the park repeatedly every single day, it becomes easier to see how giving you more training, doing serious audio work would pay off for them. Colin had every incentive to show me how he tunes vocals because he could see that I had attention to detail in tasks that had nothing to do with it.

Speaker 1 (00:32:51):

Yeah, it's just like with Nick, he didn't know anything really about video when we hired him. We just felt like it would be a good investment to give him that slot and just help him get better as he went because we believed in him. We've worked with video guys that were far more skilled than him at the time, who were just a nightmare to work with. I think some of them, and we could have easily gone with somebody like that who already knows their ship, but we decided to invest in the person with the winning personality. That's the way to do it, and I think good producers, good engineers who when they're looking for people to hire, they're looking at the character of a person because you can always teach somebody a skill. The skill part, it's not that it's easy, but that is the easy part. You can't teach somebody how to be the right kind of person, but you can teach 'em how to tune vocals.

Speaker 2 (00:33:52):

Absolutely,

Speaker 1 (00:33:53):

Yeah. And you don't want to waste your time teaching the wrong kind of person, those kinds of skills for several reasons. So the first day you were there, they make you wait for several hours. I seem to remember you telling me that you got there and then you had to sit on a couch for six hours or something.

Speaker 2 (00:34:11):

That sounds right. I spent a lot of time in that kitchen just

(00:34:14):

Waiting to be needed. A lot of that is kind of a blur to me just sitting there trying to learn the ropes, not overstep, not ask too many questions and jump at any opportunity to do anything useful. That's what the first few days were like. It was really stressful. I was stressed out of my mind to do any basic task, Hey, go to Chipotle in a city where you're not from, and it's like, oh, crap. I got to find out where the closest one is and end up several miles down the road because I went to the wrong one and the orders messed up and oh god, geez. Being an assistant is so hard because before you're in the flow of things and you can realize that the people that you work with are just creatures of habit, that you can start to predict these things and head them off at the pass. You have to learn the wants and desires of everyone around you, and before that information is known, it's kind of a whirlwind of an experience compounded with the fact that the brain is telling you how important this is, is telling you,

Speaker 1 (00:35:17):

Yeah, it's adding pressure.

Speaker 2 (00:35:19):

Yeah, it sure is. It's like the first time I was in the room and Colin handed me a guitar and he said, Hey, tune this. I have tuned a guitar plenty of times in my life after having played guitar for well over a decade, but I had never felt more pressure to get a guitar in tune than in that moment. It is like if somebody told you to tie your shoes for a million dollars, it might make you think about it a little different. And so luckily I handed him a guitar that was in tune, and then he was able to trust me with that. It is just really simple stuff, but that's what allowed me to be in the room. I'd sit on a chair in the corner, he would turn around and say, Hey, could you tune up the ES 3 35? And at the time, I didn't know what an ES 3 35 was. I googled that as quickly as I possibly could, and then I grabbed that one off the rack and tuned it.

Speaker 1 (00:36:09):

That's kind of a key detail right there was It sure is. You Googled it. You didn't say, what's the ES 3 35?

Speaker 2 (00:36:15):

Right. Not every situation is Googleable either.

Speaker 1 (00:36:18):

No, but you should know which ones they are.

Speaker 2 (00:36:21):

Certainly, and that's another important part is when you're in a situation like that, familiarizing yourself with as much as possible, even if it's not your responsibilities to know. So I walked into a room full of outboard gear that I'd never even heard of. Esoteric pieces that Rick had brought from his studio in Omaha, different vintage microphones and all of this stuff after having come from a DIY metal recordings scenario. That's a very limited scope of what the entire field of recording is all about. There are entire categories of gear that don't get talked about in the context of metal. I don't know anything about synthesizers. I didn't know anything about pop vocal mics or anything like that, and I was suddenly surrounded by all of it. If it wasn't an SM seven B, I didn't know what it was,

Speaker 1 (00:37:13):

So you looked this shit up.

Speaker 2 (00:37:15):

Of course I did. And looking it up, you find incredibly misleading threads on gear sluts and you try to triangulate what awful information you can about what it is, what it does, and how to use it, and then you just try your best to keep a hold of it to where if you're asked to go get a mic from the locker, you get the right one. It's a lot to absorb all at once, especially because the mind is being imposed upon from several different directions at once.

Speaker 1 (00:37:47):

Were you ever sitting there thinking this gig could end and then that's it? I go back to Jacksonville and it was fun while it lasted kind of thing, only every single day. Were you cool with that possibility? Where were you at concerned with that? If that had happened, would you be bummed?

Speaker 2 (00:38:07):

Oh, of course I would've. I knew the weight of what was happening, and I knew it was really just a hunch. There was no guarantee that I was going to be offered a job after this, but I knew without a shadow of a doubt that doing a good job would result in good things in my career, would result in good things in my life and would put me in contact with really good people. And so I knew that. I didn't know if I would ever even work with Colin or Rick, but I know that it also put me in good standing at the audio compound. I know that Andrew was working on UGP with Nick at the time, and if he needed guitar strung and I was just sitting on the couch, you bet your ass. I strung those guitars, and so I was just trying to be as helpful as possible to as many people as possible because I had no idea what the future had in store for me, and I knew that none of it was guaranteed and that on any given day, I could say the wrong thing. I could fuck up the wrong thing and get sent home. Lucky for me, that didn't happen, and a lot has transpired since then because of that. Really, the pressure to be fired is constant. It's just omnipresent because you're expendable. That's the nature of that position is that man, if you don't work out for any reason whatsoever, if you make the vocalist uncomfortable for 15 minutes, you're gone. Sometimes that's really all it takes. Luckily, I had enough counsel in my notebook to not do any of that.

Speaker 1 (00:39:41):

What happened next? How did that lead to not living in Florida anymore?

Speaker 2 (00:39:47):

The session was drawn to a close, and I know that Rick and Colin were kind of talking back and forth like, Hey, how do we use this kid? It's clear that he wants to do this, and he's motivated and he is willing to do damn near or anything to make it happen. And Colin at the time was in the process of getting resources together to build his recording studio at his home in North Hollywood, and he knew that I had been handy with tools and electronics and stuff like that. At the end of the record, he goes, man, you're rad. If you lived in la, I'd hire you tomorrow. I said, really? He goes, yeah. I said, okay, no problem. And so I said, just give me a month or six weeks to button up everything I have to make some money to be able to come out there and then I'll be there.

(00:40:34):

He said, cool. Well, then you're going to help build my studio. You can crash on the couch at the steakhouse if you need to for a while to hit the ground running, but for the most part, I'll have you do construction or whatever you need to do to be a part of this. And that's exactly what happened. I worked for six weeks in my home studio. I had the most successful six weeks I had ever had in my career, and then I left. I showed up and then started to work on construction for 10 hours a day, and then I would go to the studio and help finish out assisting on whatever sessions were happening, and then he would start to teach me stuff and then showed me how to tune vocals. And as soon as I knew I had to spend the other six hours of my working day tuning vocals at night and then repeating the process.

(00:41:28):

And that went on for about three months where I was working with a world-class studio builder named Alan Hug, who was one of Rick's friends from Omaha. And that guy helped me tremendously as well. Just in terms of acclimating to the West coast. I had never even been to California before. I had never even really dreamed or thought I would end up here because I think it's easy to consider yourself outside of that ecosystem entirely when you work in metal. I just thought to myself, well, I got this Florida thing. Florida death metal is a thing, so I think I could probably have a career there. So I never even considered working in a different city unless it was Montreal or someplace that was known for metal.

Speaker 1 (00:42:13):

How much of a culture shock was it to suddenly go to California and just be out of your element? Living on a couch?

Speaker 2 (00:42:20):

I mean, it was violent. It's the hardest thing that I've ever done in terms of the adage that you're a combination of the five people that are closest to you overnight, those five people changed. I still have friends from back home, but I left an entire life behind my studio in Florida is still intact with every piece in it, just sitting there. Nobody's really using it. I just left. It was hard, not in the sense that I had any regret for anything, but hard in the sense that I didn't have a safety net. It was a different ball game to get fired from California than it was to get fired from Orlando.

Speaker 1 (00:43:00):

And California has a way of chewing people up and spitting them out.

Speaker 2 (00:43:04):

Let's talk about LA rent for a second. If you're mediocre in this place and you can't hang, then you will not survive. And I've been very, very fortunate that Colin brought me under his wing and has showed me everything that he has and that we've gotten a great working relationship together. That's the only way to survive out here, is to learn how to do the work and then start doing it. And lucky for me, the construction gig and general usefulness at the beginning end of my state here sort of made it okay that I wasn't good enough at audio yet that I still had and I still do. I have years ahead of me to becoming the person I need to be to engineer for anyone in the world.

Speaker 1 (00:43:56):

The skills part is almost less important than the overall character part. I mean, granted, you have to have a certain level of skill and a certain level of ability to pick up skills. If you're getting hired to be an assistant, nobody's expecting you to know as much as the boss.

Speaker 2 (00:44:14):

That's correct. Yeah.

Speaker 1 (00:44:16):

Yeah. So that goes with the territory. As a matter of fact, if you know as much as the boss and you're getting hired to be an assistant, something's wrong.

(00:44:26):

There's a problem with that situation that would make me suspicious. Say I was hiring an assistant and they were on my level in terms of knowledge, I'd be wondering what went wrong? What's up with this person that they're not the ones doing the hiring right now. And I don't mean that as any offense to anybody, but that's kind of the way the world works, especially in this is the further you go, the more knowledge you accumulate, the more of a master of the field you become. And if you're around long enough to obtain that level of knowledge, but you're still getting assistant gigs unless it's Rick Rubin or something, you fucked something up along the way.

Speaker 2 (00:45:10):

Totally.

Speaker 1 (00:45:11):

Yeah. So I don't think that's actually a mark against you that you were not there yet with the skills.

Speaker 2 (00:45:17):

To be honest. It's kind of an advantage in some ways because if you come into a situation where you have a lot of knowledge and experience, there are opportunities for assistance that you would not get as an engineer simply in virtue of being around at the steakhouse. I've been able to be a coffee runner for high level sessions simply in virtue of being around. And then I get to see what Rob Cavallo is like producing a vocal. I get to see what he's like when he's working with an artist about song structure, and I don't think there's any way I would get to see those things if I was already a producer in my own right. You're absolutely right that the sentiment would be number one, what's wrong with this guy? He's already made successful records. Why is he running coffee for us?

(00:46:08):

And number two, people are much more likely to allow you to absorb information if you're green, if they can tell that you're not a threat to them in any way, that you're not there to steal Willy Wonka's secrets from the factory. And I think that there's something to be said about being the low person on the totem pole for a while. It gives you the opportunity to appreciate the opportunities that you get and absorb everything that you can whenever it comes your way, because it's not going to last forever. Eventually, you're just going to be working. You're just going to be working on whatever you're doing. You become an engineer or a producer yourself, and then you're off to the races on whatever you're capable of working on,

Speaker 1 (00:46:51):

And you can't stay an assistant forever. No. Like that too. If it's been five years and you haven't moved up, they're also going to start thinking, what's wrong with this

Speaker 2 (00:47:00):

Guy? Right? It's like spending too many years in college. It's the seventh year, man, you should probably finish your thesis. I would think

Speaker 1 (00:47:08):

It's exactly like that. So you have to make sure to make the absolute most out of the time that you do have in those formative years. Right? Hey, everybody, if you're enjoying this podcast, then you should know that it's brought to you by URM Academy, URM Academy's mission is to create the next generation of audio professionals by giving them the inspiration and information to hone their craft and build a career doing what they love. You've probably heard me talk about Nail the Mix before, and if you're a member, you already know how amazing it is. The beginning of the month, nail the mix members, get the raw multitracks to a new song by artists like Lama, God Angels and Airwaves. Knock loose OPEC shuga, bring me the Horizon. Go Jira, asking Alexandria Machine Head and Papa Roach among many, many others over 60 at this point.

(00:47:59):

Then at the end of the month, the producer who mixed it comes on and does a live streaming walkthrough of exactly how they mix the song on the album and takes your questions live on air. And these are guys like TLA, Will Putney, Jenz Boren, Dan Lancaster to I Matson, Andrew Wade, and many, many more. You'll also get access to Mix Lab, which is our collection of dozens of bite-sized mixing tutorials that cover all the basics as well as Portfolio Builder, which is a library of pro quality multi-tracks cleared for use in your portfolio. So your career will never again be held back by the quality of your source material. And for those of you who really want to step up their game, we have another membership tier called URM Enhance, which includes everything I already told you about, and access to our massive library of fast tracks, which are deep, super detailed courses on intermediate and advanced topics like gain, staging, mastering, low end and so forth.

(00:48:57):

It's over 500 hours of content. And man, let me tell you, this stuff is just insanely detailed and enhanced. Members also get access to one-on-ones, which are basically office hour sessions with us and Mix Rescue, which is where we open up one of your mixes and fix it up and talk you through exactly what we're doing at every step. So if any of that sounds interesting to you, if you're ready to level up your mixing skills in your audio career, head over to URM Academy to find out more. So also when you moved out there, there was no guarantee that you wouldn't just get sent back to Florida right away. Absolutely. I mean, you did talk about getting fired from California, but you didn't have a contract with Colin or anything. Did you? Just went there.

Speaker 2 (00:49:40):

There wasn't even a discussion about wage really.

Speaker 1 (00:49:43):

Okay.

Speaker 2 (00:49:44):

There was nothing in writing. There's still nothing in writing. It was just, Hey, can you do this? I need help. And emphatically, yes, yes. I would love to help in any way that I can.

Speaker 1 (00:49:56):

So there's something about the music industry that people need to know is that contracts are great and stuff, especially when you're dealing with a big company or something when you're dealing with organization to organization. But even then, the contracts only as good as your willingness and ability to enforce it. And if you think that the person's going to be shady or that you will need to enforce it, it's probably better to not even get in bed with them anyways, the first place. So in some ways, the contracts are, they're only there for the worst, worst, worst, worst, worst case scenario. And a whole lot of business gets done just on verbal agreements and trust and understandings. And I know the music industry has a reputation for being shady, which is warranted to a degree, but I think it doesn't get enough credit for how much of it gets done honorably without any paperwork, just on an agreement between two people. That's like the majority of everything I've ever been involved in.

Speaker 2 (00:51:09):

I agree. And I think I've been spoiled because I haven't really seen too much of the shady side of the Los Angeles.

Speaker 1 (00:51:16):

It's there. Believe me.

Speaker 2 (00:51:17):

Trust me, I know it's there because I hear people talk about it when they come in sessions. There's violence happening between people that are constantly trying to climb the ladder and one up each other. But the circle that I got brought into the circle of Rick and Colin and other people who are managed by Kelly, and

Speaker 1 (00:51:39):

Shout out to Kelly,

Speaker 2 (00:51:40):

Shout out to Kelly. That entire crew is good people. And to be honest, that's the reason why I just up and left to California is because I thought that I was working for good people, and I, it would be absolutely too easy to be taken advantage of by the wrong person. And then the only thing that I've had to hold for myself is that I do know how I deserve to be treated

Speaker 1 (00:52:05):

Like as a human.

Speaker 2 (00:52:05):

Yeah. It's got nothing to do with the work I know I probably deserve not to be screamed at on a regular basis or cussed at or degraded told I'm filth and spat on. Yeah, right. There's no reason for that. It happens all the time though,

Speaker 1 (00:52:18):

But that's the, okay. So it's interesting that you say that there's a fine line that one thing is asking someone to make coffee and clean the toilets. The other one is treating them like a degenerate piece of shit. That's right. And that whole treating people like a degenerate piece of shit thing is part of the old music industry. Lots of the old school guys still do that. It's not looked at very favorably anymore. People who kind of go that way, they don't get very good reputations, especially if they're under the age of 50. If they act that way, nobody's got time for that shit. They better be putting out some huge records and making a lot of people very rich if they're going to be acting that way. The only people who get away with it are old timers that it's like when your grandparents would say something racist and it's just like, oh, they're just old. Yeah. Along those lines, it's looked at like, oh, that old guy just, he's old, whatever. But lots of the dudes that I know who are from the more senior generations who are still working have completely dropped that type of working environment. They don't treat people like that anymore, even if they used to, for the most part, they don't anymore. The world has evolved, and so I think that it's important to hold your ground as far as integrity as a human

Speaker 2 (00:53:45):

Goes. Absolutely. It's something that I'm very fortunate to experience. I could have seen it very easily the other way where it was required of me to be treated like that depending on the scenario. And part of me thinks that if it was more like that, I'd still be in Florida. I would've made the choice to just try to figure it out myself, because I am very concerned on a fundamental level about who I'm working with and who they are that matters to me far more than what they've done or what they've been responsible for, and many aspects of this. And I think that that has been beneficial to me because choosing the right people who happen to be talented, who are just there to have fun and make music with their friends, that's what I think embodies a lasting career. And that's something that I've learned intimately from Rick, that I've learned from Colin and from the whole crew, is just that money gigs aren't really worth it.

(00:54:43):

If you're doing things that make you hate yourself and hate what you're working on, it's much better to just have a good time and be relaxed and work on stuff that you're stoked on with people that you like. It's really the relationships that are going to carry you through things. No individual mix that you work on. No song that you engineered is going to make or break you in the grand scheme of things. It has much more to do with, did these people like hanging out with you when they made music, and did they have a positive association with your vibe whenever they leave a session? And yeah, I think that having a good moral compass about it is more important than any piece of knowledge that I could have about gear or anything like that.

Speaker 1 (00:55:27):

You told me that Rick told you about loyalty once, and loyalty is super important to me. I think that to me, that's one of the most important character points in a human is how loyal are they? Will they just throw you under the bus right away, stab you in the back right away, take advantage right away? Or are they loyal? I think loyalty goes a super long way. He told me that Rick basically told you that at some point.

Speaker 2 (00:55:54):

That's correct. In no uncertain terms. He said, look, there's a chance that you'll be offered other opportunities as a result of having done this work or been a part of this or that. But it's important to give back to the people who take you under their wing. And I believe that firmly that I owe it to my people. That's what my labor is to me. When I sit down and do the work and sacrifice my body and all of these things, at the end of the day, if I ever have to wonder why I'm doing this, it should be ideally because I have some people that I really don't want to let down because I'm loyal to them and I'm loyal to what they work on, and I want to be a good friend. Really. It's like if I miss a deadline for printing stems or something like that. I'm letting down a lot of people if I export something that's not right. It's not just my name, it's the name of people who have trusted me a lot and who have taught me a lot, and I think that matters immensely. Everything you do is sort of pregnant with loyalty and with trust.

Speaker 1 (00:56:59):

I agree.

Speaker 2 (00:56:59):

Yeah.

Speaker 1 (00:57:00):

Let's talk a little bit about what you've done since you've been in California. So it's a culture shock, but you've been there a while now.

Speaker 2 (00:57:07):

I have been here just over a full year,

Speaker 1 (00:57:09):

So shock is worn off and it's now what you do.

Speaker 2 (00:57:12):

It's what I do every day.

Speaker 1 (00:57:13):

Yeah, yeah. What's your life been like out there?

Speaker 2 (00:57:16):

I am no longer sleeping on the couch. I have graduated from that. I live in a house with my girlfriend and her family 20 minutes west of the studio, and so I drive in through beautiful sunny conditions every day to try to get here before Colin and then I stay until after he leaves. And on any given day, it can be a session for writing, it can be sessions for albums that we're working on. It can be mixing. It's a huge swath of possible jobs because of what Allen is capable of working on. He can write in any genre he can produce in any genre and he gets sent a lot of different stuff. So on any given week, we could work on projects that are all across the board and it's my job to engineer and assist and be whatever needs to happen in the room.

(00:58:10):

It's just me and Colin in his production suite at the steakhouse. There's no additional assistant unless we go to a bigger studio to cut drums or do something like that. So I'm still not above taking out the trash. I still do all of that stuff. It's just a matter of what can I be trusted with and then we sit down and we crank out records. Now we're to the point where he can trust me with enough to say that I engineered a record that we worked on together. That's just the dream because I started as a lowly assistant last February and now I get to do what I set out to do and have my name on records that go to radio records that millions of people will listen to, and I'm finally starting to get those projects under my belt. We've had the first few records where we've done them together. Collins on production. He's also a brilliant engineer.

Speaker 1 (00:59:07):

Yes, he's great.

Speaker 2 (00:59:09):

That's what's kind of funny about this is that I have engineering credit on these records, but he still lifts a lot of weight when it comes to sounds that he's looking for and it's kind of my job in certain instances to read what he's trying to do and that flow has gotten better over time, so I know if he's looking for a clean chorus guitar part, I know what guitar to hand him that's already tuned with the type of tone that he's looking for, and that's really where the magic happens. If I do my job really well, he doesn't have to think about what it sounds like as much or to any degree if I nail it, he sits down and he plays a part. It goes into the cubase session and then we move on and basically he cranks out a song in a day.

(01:00:02):

They will sit down with nothing, no stems, nothing to drop into the session. It starts with a blank template and by the end of the day you have a song that mostly sounds mixed and barring a few tweaks can be ready to do some damage in the world. That is super cool. I get to work on productions every single day and everything is different and the pace is frankly ridiculous. I was trying to add it up the other day and there's no way that I've worked on fewer than 150 or 175 different songs since I've been here.

Speaker 1 (01:00:37):

That's craziness.

Speaker 2 (01:00:39):

Yeah, it's insane. And even just the list of artists that I've worked with.

Speaker 1 (01:00:44):

Can you name any?

Speaker 2 (01:00:45):

Yeah, yeah, sure can. Some highlights. I've worked in some capacity on Papa Roach on three 11 on one oh Rock on Dreamers on Collin's own project, which he got off the ground since I've been here called American Teeth. We did a record with Form Ashes to New, we're in the processes of finishing up a record with Teenage Wrist, the head and the heart. I mean, it goes on and on and I know I'm forgetting plenty of stuff that's really significant even, but something awesome walks in the door every single day and I don't always know what it is. One of the first days I was here, I got done with construction and then I walked in the room, it was like 10:00 PM at night there there's a vocals track, and so I quietly sit on the couch. This guy just lets a vocal rip. I go, man, I know that voice, dude is this puddle of mud. Yeah, it was puddle of mud. That was the first time it was like, oh wow, okay. It is just what it's like to work on stuff that's on the radio every day that I grew up where it was on the local rock station.

Speaker 1 (01:01:49):

Now you're in the room with it.

Speaker 2 (01:01:50):

Now I'm in the room and what's super cool is when you hear an iconic voice that you're used to Jacoby from Papa Roach, when you hear him in the room, that's what it sounds like

(01:02:03):

When he sings into the mic. It sounds like a record. That's been one of the coolest things about working in this sphere. It's not even limited to vocalists. If you have a session drummer or an excellent guitar player, whenever they play, it sounds like a record and you have to do very little when it's right, of course it's going through awesome gear and every part of it is as good as it can be in every category. Then by the time it gets into the session, it's just awesome. Downstairs, there's an epic hand wired Neve console and there are moments sometimes where we'll be down there getting a guitar tone and Colin will have an idea for a stereo chorus that uses two different amps and then two different sets of stereo room mics that he can manipulate in different ways using the console. And there's sometimes where a guitar player will just strike a chord and you just have to sit there and go, wow. Oh my God. That sounds incredible. It's not to say that you can't do these things in the box or anything like that, but there's powerful experiences to be had when all of those factors are correct.

Speaker 1 (01:03:13):

Absolutely,

Speaker 2 (01:03:14):

Yeah. When you're in front of a giant desk and there's Asperger's blaring the drum sounds that you just tracked and all of this stuff, and you can sit back and say, holy shit, this guitar tone is so sick, it might inspire someone to play this snare is so fat that we might not have to use a sample. It's just awesome. Those are the moments that really make me love what I do, and the artist knows it too. They're sitting on the couch, they're sitting in front of the desk, they're listening, and when you can blow their minds with a tone when the part is just correct and you hit play and everyone just agrees, it's like, yeah, that's it. Cool. Let's move on to the next part. That's the raddest clean tone we've ever been responsible for. That's just too cool, especially working in a studio with history and all that stuff behind it.

(01:04:02):

There have been a lot of sick records made here at the Steakhouse. There have been a lot of sick records made at other studios that we go to for drum stuff or whatever in North Hollywood in a two mile radius. There's some of the most famous studios in the world. The things that you have access to geographically are really incredible, and truth be told, when I was in Florida, I had never even stepped into a professional recording studio that just didn't exist. I had never touched an analog console before. I touched the Neve at the steakhouse and now I get to drive it and it's wonderful.

Speaker 1 (01:04:36):

So speaking of being in a small town, let's talk a little bit for or at people or with people who kind of are in a humble position. You were in a small town, Jacksonville has nothing going on. It may as well be the middle of Idaho as far as I'm concerned. I know Jacksonville, my stalker is from Jacksonville and I've worked with Jacksonville bands and it's basically a middle of nowhere kind of town. A lot of people think to themselves, there's no opportunity here. How do I make it work? What do you say to that?

Speaker 2 (01:05:15):

I'm going to say that it's possible, but boy, it's an uphill battle. The most beautiful thing about being in Los Angeles is just that there's people down the hall at the steakhouse. Tom Rau is down there and he was Rick Rubin's engineer on audio slave and stuff, and he's got nine Latin Grammys and you can just ask him stuff. You can say, Hey Tom, how do you deal with orchestra in a dense mix? And he'll just be like, oh, you just do this. It's like, thanks, man. There's no resource like that for you. When you're in a small town like that. There's no gurus and usually if there are gurus, they're like grizzled local studio warriors who hate clients, who can't seem to get above whatever echelon they're working at, and it's rough to take advice from those kinds of people. Ideally, when you're working in audio, you should be getting your information from people who have done records that you care about.

(01:06:13):

If you're asking for advice on a guitar tone, it's probably best to make sure that the person you're asking has done something that you think is just the bee's knees. And in Los Angeles, that's where those people live. That's where the studios are. That's where prolific music shops are in Jacksonville. There's Guitar Center and that's it. It's not even like the Hollywood Guitar Center, which that plays rules in comparison to what we have down there where there's no awesome instruments there. There's nothing totally inspiring to where if you need something during a session, you can guarantee that they'll have it. You need to think ahead and order everything online for your session to make sure that you have remo drum heads. So

Speaker 1 (01:06:56):

Do you think that people should try to get out of their town and move to somewhere like la? What do you think they should do?

Speaker 2 (01:07:02):

I can't categorically recommend moving out here because I can't speak for what it's like to do it on your own.

Speaker 1 (01:07:09):

Yeah. Well, you did the thing that I've always said to do, which is get the opportunity first.

Speaker 2 (01:07:14):

That's right. I wouldn't have come out here without a job straight up. I would've been comfortable sort of hacking through it on my own. But yeah, I recommend that you at very least seek out someone whose work you care about and figure out what you can do to help. It's not always going to be obvious, but something that I learned is the best way to do it is to bring them work. If you really like someone and you want to get a working relationship with them and they do mastering, try to sell your clients on getting their songs mastered by them so you can open a dialogue and figure out what they need if they need editing, if they need this or that, if you've got drum samples that might be of interest to them, figure out some way to add value to what someone else is doing, and then an opportunity might come from that.

(01:08:01):

It makes the utmost sense to me that nobody would really want to hire someone who just asked for a job. Of course not. Right. There's very few industries for which that would be an effective strategy, and I'm going to say especially not this one. There was a moment that happened to me fairly recently where we were at Clear Lake tracking drums for this rock project and one of the assistants was helping me put mics on stands and stuff like that because I had my input list and how I wanted everything patched when I walked in the building. And he turned to me and he goes, man, how do you get on these high level rock sessions? I was confused that he had asked me that because he came from an audio school, he didn't know what to do in order to be able to engineer things in order to be allowed in the room.

(01:08:56):

And it was confusing to me because I'd never been asked that as somebody who had made it. I was just like, man, I'm just setting up mics. What do you want from me trying to get a drum sound? But it occurred to me that the question was absurd that I tried to do my best to correct him and say that you need to figure out how to create an opportunity for yourself by figuring out what sessions you want to work on, and then not everything is attainable is reasonably attainable. You can't just decide that you're going to go work on the next Justin Timberlake record because you think you've got the stuff and you can contribute to that. But I think it's reasonable to set goals where you say, Hey, I really like this person's work. I wonder if they need help. And they won't always, but sometimes they do. If what they need done is something that you can do, then that's where the offer needs to happen. It's not a question of how do I be here? What can I do?

Speaker 1 (01:09:56):

Yeah. Instead of How do I get on these big ass rock sessions? It's more like, how can I provide value for people who work on big ass rock sessions?

Speaker 2 (01:10:08):

That's exactly

Speaker 1 (01:10:08):

Right. And it's like a similar question, but you'll get totally different answers.

Speaker 2 (01:10:15):

And that's also not to say that I'm an authority on any of this because I am still so green and anything that I say with regard to audio, anything that I say with regard to doing this as a career, I'm really just synthesizing from people that I trust and that I know I have a lot of Rick sensibilities in my brain at all times. I have a lot of wisdom that Colin has told me. I have a lot of stuff that I've gotten from you, stuff that I have written down in my notebook that I keep with me for every session that I'm on, and it's just a matter of trying to take all of that information, and it can be information that you get on the internet from people that you don't even know, that don't even know you. But I think keeping all of those things together and using that kind of as your compass is the most useful thing that you can do. If you're looking to work on things that are bigger than you're capable of,

Speaker 1 (01:11:10):

The more you make it about other people and the less you make it about you, the better off you're going to be. I think

Speaker 2 (01:11:16):

That's right.

Speaker 1 (01:11:17):

It's like a long play way of getting yours, I think mean at the end of the day, we have to look out for ourselves, but I think that in order to truly look out for ourselves, what we need to do is make as positive of an impact on other people as possible. And then as a result, they'll take care of you basically.

Speaker 2 (01:11:39):

That's correct.

Speaker 1 (01:11:40):

What's next? You just see yourself doing this as long as it plays out. Basically,

Speaker 2 (01:11:45):

That's the discussion that I had, my yearly self-performance review. It's like, okay, that was a lot. Where do I stand? What do I even want to do? And I've had these discussions with Colin and with Rick and with Alex pto, who also has a room at the steakhouse who I love dearly. I love him too. Without being annoying, I try to poll my council members and see, man, what do you think I should do? Should I start building my own rig? Should I start doing this or that? And Rick's advice has stuck with me recently, and I was like, man, if I want to get a vocal chain, what should I buy? Because he's the guru of gear. And he goes, well, dude, what do you want to specialize in? And I hadn't really thought about it in those terms because I think there's a lot of pressure to be good at everything these days because of the job of what's expected from a producer. That's also my somewhat distorted view because Colin can kind of do it all.

Speaker 1 (01:12:46):

He's a freak though.

Speaker 2 (01:12:47):

He's a freak of nature, and what I've come to realize is it's not really fair to hold myself to standards of the way that I see him working and that I do need to figure out what I really like doing, what I'm good at and what I can do to make awesome records. And I think that as it stands, I trust myself to track guitars on a record. I trust myself to set up a drum kit and have it be reasonably slamming by the time he walks in the room. I trust myself to edit a record. I trust myself to tune vocals for anyone, but that doesn't answer the question of, well, do I actually want to be a producer? Because at present, I'm a budding engineer. I'm not even involved in the creative process of structuring music and determining the arrangement and deciding what should be in it. I think too that there's a lot of different breeds of producers. There's the Rick Rubin style where he doesn't drive the console at all. He sits on the couch and has prolific thoughts about the music,

Speaker 1 (01:13:44):

And he hires the right team.

Speaker 2 (01:13:46):

That's right. I'm going to say that that is more rare or disappearing increasingly because of how quickly things are working, and there's monetary consequences of the times as well is that budgets aren't as big and you kind of have to get creative, but currently my plan is I'm on the best team that I could possibly be a part of, and I am going to contribute to that team doing everything I can and pushing myself to get better on my hit list is I'm going to start taking vocal lessons and I'm going to start taking piano lessons because there's no way that learning those things won't help you track even if you're not the one doing it. Understanding how to coach a cadence out of a vocalist is something that you have to experience for yourself. I think that seeing the multi-instrumentalist talents of Colin have kind of inspired me to realize that the more musical you can be, the better you're going to be at this.

(01:14:45):

There will come a point maybe within the next year that all of the technical side of things is really just second nature. You're kind of going through the motions of making stuff sound good, and it's just what you do, but being able to make ideas more musical, and even in your mixing, even in your editing, Colin showed me how to edit musically and not edit to fix things. That's a different concept is that every aspect of music making is an opportunity to make creative decisions. There's no part of this process that can be boiled down to just apply plugin, turn knob done. There's immense creativity to be had, and my job is to keep working on my bag of tricks, keep working on my set of known working signal chains and all of these things to where I don't have to think about it. I know how to get what I'm looking for, and then I do it and I can remove that from the table. So I want to be able to cut a vocal for anyone. I want to be able to step into any room. It doesn't matter if I've ever used that console before. I want to be able to step in there and crush it. Part of that is just do your research. Most studios will show you a list of their mic locker and all of that stuff, but I've also gotten to see what it actually means to be good at pro tools.

Speaker 1 (01:16:14):

Yeah, it's crazy when you see someone who's really good at it.

Speaker 2 (01:16:17):